Let The Beat Drop: Dancehall Censorship In Jamaica

Introduction

Boasting its fiftieth year of independence, the Greater Antillean isle of Jamaica touts a large and progressive musical catalog that makes the industry one of the country’s most internationally known exports. Indigenous to Jamaica, reggae is a calming music that inspires tranquility and feelings of adoration. In contrast, dancehall music is more upbeat and often a more raunchy relative of reggae. Lyrically, reggae is closer to Standard English, making it more internationally accessible then patois, or Jamaican Creole, often used in dancehall. Dancehall is a popular music style amongst Caribbean youth, but rarely receives respect from other demographics due to its lyrical content. Since the early 1990s, dancehall has been lambasted for homophobic content that inherently advocates violence against homosexuals within Jamaica. LGBT organizations such as British Outrage! and the U.S. Human Rights Watch have taken to lobbying corporations against sponsoring dancehall artists and against promoting concerts for popular dancehall acts. These groups cited more outdated songs that had become less popular and were only re-popularized by attention brought to them by their criticism. In fact, some of the individuals targeted had last penned homophobic lyrics more than a decade earlier. [1] As a result of lobbyists fighting against dancehall, the international careers of some artists, including Buju Banton and Shabba Ranks, were temporarily or permanently stunted in the early 21st century. The non-governmental Recording Industry Association of Jamaica, while supporting the condemnation of insensitive lyrics, has labeled the attacks from gay rights organizations a challenge to Jamaican sovereignty. [2] Amidst this turmoil, the Jamaican government missed an important opportunity to decry lyrical advocacy of violence against homosexuals, furthering confrontations with the international community.

The 2009 Censorship Directives

Frequently ignored by non-enthusiasts, at its core dancehall shares characteristics with its more illustrious, ubiquitous musical predecessor, reggae. Segments of dancehall, especially subgenre “conscious reggae,” serve as contemporary agents against oppression while channeling itself as the voice of the downtrodden. Given dancehall’s status as a symbol of the working class, the elite controllers of society previously allowed the genre to operate freely as long as it remained within the confines of its core audience. In fact, the government stood against the international community by neglecting to attempt its regulation, including the removal of homophobic lyrics, due to its the acceptance of within the general Jamaican population.

While the dissemination of abusive lyrics was tepidly condemned by the 1996 “Television and Broadcasting Commission Regulations,” of the Broadcasting Commission of Jamaica (BCJ), homophobic content was inadvertently condoned by section 30(a) of the regulations which states that, “No licensee shall permit to be transmitted [for] any matter in contravention of the Laws of Jamaica”. [3] This statute is significant when taking into account Jamaica’s antiquated English buggery law, which criminalizes anal penetration. In sanctioning homosexual activity, the government unconsciously accepts statements that berate homosexuality. While the indifferent attitude of the government caused international relationships to somewhat suffer, it would have caused too great an upheaval in Jamaican society to defend the positions of international human rights groups, due to government respect of the deep embedment of conservative Jamaican moral values.

Despite the presence of the Jamaican moral code, caustic reference to homosexuality in dancehall lyrics is not deeply rooted in the history of the music. A common, yet related theme characterized by excessive reliance on sexual leitmotifs has been present since the genre’s inception in the 1980s. Before the advent of technology that allows a more fluid dissemination of music, the descriptive vulgarities of dancehall were delegated to late night dancehall sessions. They were kept off the radar of the older, more traditional generation, and out of the reach of the impressionable youth. As a result of internet downloading, smart phones and the utilization of car stereos, in 2008 everyone on the island was bombarded by the titillating “Ramping Shop”. [4] The carnally explicit song disturbed society’s traditionally demure into action in a way that homophobic lyrics did not.

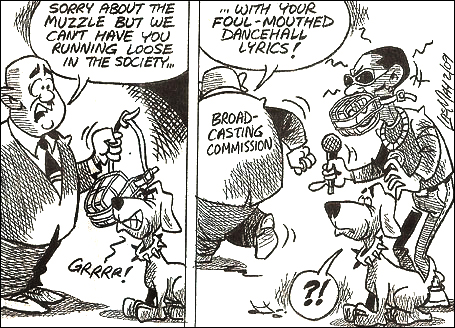

In many ways, the Jamaican movement against dancehall was similar to that of the Parents Music Resource Center movement against rock and hip-hop in the 1980s in the United States. Similarly, domestic dancehall opponents argued dancehall actors behaved in ways that could not be ignored because they disrupted moral standards and poisoned children, subjecting them to constant visual and auditory examples of promiscuity. [5] Performed by DJs Vybz Kartel and Spice, “Ramping Shop” is replete with homophobic slurs and aggressively sexual lyrics, which ultimately led to the February 2009 BCJ directive severely censoring the song as well as the entire sub-genre of music in which it was classified. [6] Although the directive explaining the decision to censor dancehall music did not list any specific songs or videos as the reason for the decision, it did specify they believed the “daggering” sub-genre of dancehall music directly violated previously established broadcasting regulations regarding the dissemination of explicit material. [7]

The 2009 statement did not introduce new regulations, only new methods of handling previous legislation. For instance, where bleeping out the distasteful lyrics was previously allowed, the new directive no longer permits media houses to use original songs with bleeped material. As a result, artists are now forced to create dual versions of songs to remain in radio rotation; the original raw, unedited version of their songs must be accompanied by a clean, edited version with double entendre replacing the graphic lyrics of the raw version. The raw versions are only deemed acceptable in the physical dancehall space while the edited versions are distributed to radio and television stations.

Conclusion

In the years directly following the 2009 directive, lyrical content has altered in ways that are more appeasing to the desires of the BCJ and the Jamaican public. More creativity has emerged on the music scene and instances of daggering no longer burden songs. The newer face of dancehall is still not as defined as many wish for it to be— sexually explicit lyrics, while rightfully removed from the airwaves, still manage to find a continued presence off of radio and television frequencies. Side-by-side comparisons of artist lyrics pre- and post-2009 clearly show the continued presence of vulgarities, but in more cerebral or endearingly profane forms. [8] Violent and aggressive sentiments still exist but popular artists are paying homage to their lyrical forefathers through political commentary in addition to the unscrupulous materials that initially merited the ban. [9] According to artist Ce’Cile, the year following the ban, veteran artist Bounty Killer, known to be a frequent offender of the directives regulations, agreed with the censorship imposed by the government and the confinement of vulgarities to spaces attended by adults. [10] Others, such as popular conscious dancehall artist Konshens, have continued fears that censure will diminish marketability. While the Broadcasting Commission has not furthered the ban, it claims to be constantly watching the dancehall environment should the need arise for it to interject itself into the recording booth in the future. [11] With one of the liberated presses in the world, especially with consideration of regional neighbors, further censors on music seem counterproductive to social growth in Jamaica. [12] The 2009 standardization of music distribution has proved effective, but intensification of prior censorship directives could contribute to the stagnation of Jamaican open social society if extreme care is not taken to defend against repression of expression.

Aleia Walker, Research Associate at Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Sources:

[1] Oumano, Elena. “Jah Division: Free Speech, Cultural Sovereignty, and Human Rights Class in Reggae Dancehall Homophobia Debate.” The Village Voice 50, no. 7 (2005): 28-30, 32. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1220742?accountid=14585.

[2] Davis, Dawn A. 2004. Anti-gay controversy reaches boiling point in dancehall. Caribbean Today, December 1.

[3] Jamaican Broadcasting Commission. 1996. The Television and Sound Broadcasting Regulations, 1996. Kingston, JM. Section 30 (a).

[4] Palmer, Addijah. Ramping Shop. From Pon di Gaza 2.0. Tad’s Record Inc. 2008, compact disc.

[5] Tyson, Esther. 2009. ‘Rampin’ Shop’ – Musical Poison. The Gleaner, February 1, Commentary.

A letter in the commentary section of The Gleaner written by school principal Esther Tyson branded “Ramping Shop” musical poison and became additional incentive to spur the Broadcasting Commission into action as it was published five days before the February 6th ban as there were also multiple rebuttal and response articles published in the print media following Tyson’s article.

In dancehall, a deejay is equivalent to a rapper in hip-hop.

[6] Jamaican Broadcasting Commission. 2009. Statement by the Broadcasting Commission on Actions and Recent Directives Relating to Broadcasting Media Content. Kingston, JM.

[7] Jamaican Broadcasting Commission. 2009. Statement by the Broadcasting Commission. Kingston, JM.

The commission defined daggering as a colloquial term or phrase used in dancehall culture as a reference to hardcore sex or what is popularly referred to as “dry” sex, or the activities of persons engaged in the public simulation of various sexual acts and positions. A statement released May 22, 2009 clarified that the commission had not and had not intention of compiling a list of banned songs and videos and had no intention of doing so per international broadcasting regulations. The Television and Sound Broadcasting Regulations were originally published in 1996 and amended in 2007. The statues, the Television and —Sound Broadcasting Regulations and the Children’s Code for Programming of 2002 both have guidelines for regulating explicit material. As defined in the February 6, 2009 directive the statutes relating to music broadcasting are Regulations 30(d) and 30(l) of the Television and Sound Broadcasting Regulations. The degrees of explicitness for violence, sex, and language are detailed in the “Children’s Code for Programming”.

[8] Lawrence, Sheldon. Flying Dagger (100 Stab). From Sky Daggering Riddim. Equiknoxx Records. 2008, compact disc.

Lawrence, Sheldon. 6:30. From 6:30 Riddim. Notnice & Corey Records. 2011, compact disc.

Palmer, Addijah. Neva Get a Gyal. From Ducati Riddim. Black Street Music. 2010, compact disc.

Palmer, Addijah. Ramping Shop. From Pon di Gaza 2.0. Tad’s Record Inc. 2008, compact disc.

I compared lyrics of Aidonia’s “100 Stab” (2008) and “6:30”(2011) and Vybz Kartel’s “Ramping Shop” (2008) and “Neva Get a Gyal (Never Get a Girl)” (2010). Both lyrical daggering offenders, I found these two artists to be a small representative sample of the contentions within dancehall.

[9] Davis, Anthony, I’m Okay. From One Day Riddim. Seanizzle Productions. 2010, compact disc.

For example see Beenie Man “I’m Okay”. The 2010 song expresses the feelings of the artists following the revocation of his United States visa. Following the 2010 extradition of Christopher “Dudus” Coke, the U.S. visas of many prominent dancehall artists were revoked.

[10] “Broadcasting Commission Directives (3 of 5).” [3/20/2010]. Video clip. Accessed September 3, 2012. YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3-OmVQTldPc&feature=relmfu.

[11] “Cordel Green Speaks on the Issue of Payola.” [6/27/2011]. Video clip. Accessed September 3, 2012. YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTzRN6RgpMw.

[12] “Press Freedom Index 2011-2012.” Reporters without Border. 2012. Accessed September 1, 2012. http://en.rsf.org/press-freedom-index-2011-2012,1043.html.