Venezuela, Violence, and the New York Times: Failing When it Comes to Selective Indignation

By Charles Ripley, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs with contributions from Larry Birns, Senior Editor and Director at COHA

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

Abstract: The Venezuelan protests that emerged in the beginning of 2014 attracted a wide range of academic and media attention to the quality of its reportage. The protests centered upon the nature of the opposition to the current President Nicolás Maduro (2013-present), the successor to former President Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (1999-2013). One of the most controversial issues pertaining to the political unrest was the tone of U.S. media coverage. Supporters of Chavismo claim that the U.S. mainstream media tends to focus on governmental abuses while ignoring the violence perpetrated by the opposition. Despite the widespread attention the crisis has generated, there has been little effort to systematically test the extent to which the violence is attributable to governmental forces and whether or not the U.S. media has accurately and dispassionately covered the events. Creating the first political violence dataset for the Venezuelan crisis, this research aims to measure the extent to which the U.S. media outlet, led by The New York Times, objectively covered the 2014 crisis. Results suggest that although the New York Times accurately reported governmental violence, it significantly underreported opposition violence. The study presented here not only hopes to broaden one’s view of the Venezuelan crisis, but aims to contribute to a wide range of academic and policy studies, including Latin American politics, political violence, and media studies.

“Somos dueños de nuestra historia . . . ya sea buena o mala la tenemos que escribir nosotros”

- Uruguayan President José Alberto Mujica Cordano (2010-2015)

Introduction

Since Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (1999-2013) was elected president of Venezuela in 1999, the country has attracted a wide range of scholarly and media attention. The waves of protestsand other forms of violence that began to destabilize the nation at the beginning of 2014 very soon was receiving special coverage. In addition to the much-expected absorption of the subject by academics, journalists, professional athletes and Hollywood entertainment stars took sides. Even socialite Paris Hilton tweeted about her findings about the country of Venezuela: “Praying for Peace in Venezuela. Such wonderful people, they don’t deserve this.”[i] The political unrest that left over forty people dead, hundreds wounded, and millions of dollars in private and public property damage is extremely complex to entirely understand. Nevertheless, much of the situation can be broken down between supporters of Chavismo, the Center-left movement based on the policies of Hugo Chávez, and the opposition movement. Supporters of current president Nicolás Maduro (2013-present), Chavez’ successor in the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela Party (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela) (PSUV), argue that Chavismo is a legitimate democratic movement. The protesters, on the other hand, tend to be members of the upper-class elite that aims to overthrow the democratically-elected president and desire to roll back the social and economic gains the poor masses have experienced through the “Bolivarian Revolution.”[ii] Essentially, protesters want to return the right-wing oligarchy and middle-class political base to a position of pre-eminence back to power. The opposition however, accuses the government of promulgating authoritarian rule and of being guilty of gross human rights abuses. For the opposition, the demonstrations stem from the government’s mismanagement of the economy, destruction of political institutions, and the excessive use of force against peaceful demonstrations.

One of the most controversial issues pertaining to the political violence and persistent unrest in Venezuela is the nature of media coverage in the United States.[iii] A number of scholars, journalists, and activists claim that the U.S. mainstream media tends to focus on governmental abuses while ignoring the violence and destruction perpetrated by the anti-Chavista demonstrators.[iv] In June 2014, Al Jazeera published an article suggesting that U.S. and international news outlets have completely dismissed both the right-wing violence and the accomplishments of the Venezuelan government under President Hugo Chavez, which had lasted fourteen years. Citing gains in rural land reform for an estimated 400,000 peasants and individuals negatively affected by a long history of right-wing attacks, the article contained that such objective information “doesn’t fit with the narrative” of an oppressive leftist government against peaceful demonstrations. Additionally, others have pointed out that the U.S. media inflates the extent and depth of the demonstrations.[v] Mark Weisbrot, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington D.C., points out that protests have been only narrowly concentrated in a few upper-class neighborhoods. “I came away skeptical of the narrative, reported daily in the media, that increasing shortages of basic foods and consumer goods are a serious motivation for the protests,” he observes after travelling to Venezuela in March 2014, “these people [average citizens] are not hurting – they’re doing very well. Their income has grown at a healthy pace since the Chávez government obtained control of the oil industry a decade ago.”[vi]

The accusation of bias coverage is not limited to Venezuela.[vii] Some sources observe that bias is common and intense against the rise of the manifestation of the new South American left. In the widely-read Huffington Post, William K. Black accused the New York Times (NYT) of unbalanced coverage between Italy’s former Prime Minister (2011-2013) and Minister of Economy and Finance (2011-2012) Mario Monti and Ecuador’s president Rafael Correa (2007-2017). Although both hold a Ph.D. in economics, Black contends that “the New York Times treat[s] Monti reverentially and Correa dismissively.” Black concludes that this kind of double-tiered coverage is ironic since Correa has been much more successful in handling Ecuador’s economy than Monti has with Italy’s.[viii] The Washington Post has also been criticized for its comments on President Nicolás Maduro. An editorial in the Washington Post described the president as an “economically illiterate former bus driver.”[ix] The Council on Hemispheric Affairs (COHA), a think tank that focuses on Latin America, derided the Post’s article as an “ad hominem attack with misinformed smears.” “The Post’s views,” such as post-critics director Larry Birns, Mills, Pineo counter-editorial observe, “appear to have been formed by uncritically accepting all of the propaganda offered up by the right-wing opposition press in Venezuela.”[x]

These are no trivial accusations. The responsibility of the media is to inform the citizenry on domestic and world events. The information generated by news coverage often guides public opinion and influences governmental courses of action. In short, coverage informs policy. It is also worth noting that prestigious newspapers often affect scholarly research. “In addition to producing much of the information available to government agencies, protesters, and rebels,” Baum and Zhukov point out in their own research on media bias, “news organizations generate the text corpora social scientists use to study political movements.”[xi] As a result, the media plays a pivotal role in how academics develop research questions, find evidence, build datasets, and make scholarly conclusions.

Despite the seriousness of such accusations, they are not often tested. In the absence of any frequent formal scholarly treatment, we only stand witness to the two major protagonists (pro- and anti-Chavistas) fighting it out through a wide range of media outlets, including radio, television, newspapers, blogs, and tweets.[xii] This research aims to fill an important gap in the literature surrounding the subject. Evaluating the role of the media, however, is not easily reducible to hypothesis testing and yes and no conclusions. Nor would it be possible to analyze all U.S. coverage of the Venezuelan crisis. Instead, this study specifically focuses on the New York Times and the extent to which it offered a fair or not a balanced understanding of the crisis. Focusing on the NYT is useful for two reasons. First, the NYT has been a focus of criticism over its coverage of Venezuela. Even famed director Oliver Stone attacked the NYT for calling the 2002 coup against Chávez a popular uprising and, since the rise of Chávez, has had a back-and-forth with the media outlet.[xiii] But even more importantly, the NYT is influential not only in policy and academic circles, but also with the broader rings of the U.S. public. It remains one of the country’s most reputable news sources and is often considered a more objective alternative to other sources such as the conservative Wall Street Journal. The NYT’s own apology for misinformation regarding weapons of mass destruction leading up to the 2003 war in Iraq highlights the paper’s importance and its influence over policy makers and the general public.[xiv] What is more, the fact that President Maduro, the former president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello (PSUV), and the government’s main critic Leopold Lopez all published op-eds in the NYT (Maduro even purchased space in the newspaper to explain Venezuela’s side of the recent Colombia-Venezuela border controversy) attests to its influence.[xv] Therefore, the NYT merits attention due to its alleged bias against South American leftist political movements and its scope and importance of its readership.

As the tables indicate, the time under study is from February 2014 to February 2015. Limiting the research to this specific time frame has produced a number of advantages. First, mass protests, particularly in areas where the opposition is popular, emerged at the beginning of 2014 and began to fizzle out by the beginning of 2015. Focusing on this one-year period allows for a more accurate and in-depth understanding of the NYT’s coverage of Venezuelan politics. Essentially, the research is more manageable. There are literally thousands of sources, points of views, and stories to be told regarding the rise and rule of the Bolivarian Revolution. Focusing on a year of protests is a workable duration of events and sufficient coverage to test the continued accusations. Moreover, objectively coding for political violence and constructing a dataset offers a well-rounded snapshot of events without falling into confirmation bias. Supporters of Chavismo can simply cite protestor violence while members of the opposition observe governmental abuses. Information has become politicized. The research herein aims to offer a relatively more balanced perspective.

It is also important to note that Venezuela has undergone significant changes. Since the limited time under study, Venezuela has suffered new waves of protests that have emerged after the opposition won a super majority in the Venezuelan National Assembly in December of 2015 and the Supreme Court dissolved it in March of 2017. To replace the National Assembly, Venezuela held its first Constituent Assembly vote on July 30th, from which the opposition party Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) abstained in protest. This move, which the opposition calls a coup, has sparked more protests throughout the country.[xvi] As a result, the findings presented here are limited to the specific timeframe mentioned above. Nonetheless, the bias in coverage found in these accounts may be present in the current reporting of Venezuelan politics. Consequently, this should be a subject for future research on the ongoing Venezuelan crisis.

Methodology

The main methodology this time relies upon a different bouquet of qualitative coding. In a nutshell, coding organizes raw data into a more organized and systematic form. This process often entails assigning value to the specific economic, social, or political phenomena under study. In the case of Venezuela presented here, we rely upon what Johnny Saldaña calls magnitude coding.[xvii] Laying out each incident of political violence, we assign the magnitude value of high, medium, or low.[xviii] An act that results in the death of a student protester, for instance, would be high, whereas deliberately spilling gallons of oil in a street out of protest would be low. Medium, on the other hand, could involve slight bodily injury, forcible movements, and threats. We further attribute the act of violence to one of three categories: government, opposition, or accident. Creating another dataset for the NYT’s coverage, it is then left to compare the datasets to measure the extent to which the NYT provided balanced coverage. For the purpose of transparency, as well as to almost invite criticism, we opted to include the datasets (see Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4) in the main article instead of a coding handbook.

In addition to offering a better understanding of Venezuelan political events, this research creates a more reliable dataset for political violence in Venezuela. In the academic community, political scientists have assumed the responsibility of creating datasets to measure such concepts as democracy, terrorism, and political terror.[xix] Despite having scholarly value, these datasets often fail for Latin America for two reasons: Sources and funding. Datasets rarely rely on area experts or on the people of Latin America themselves. Sources are usually U.S. institutions that have invested interests in Latin American politics, such as the Department of State and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Teaching and research assistants, most of whom know little or nothing about Latin America, quickly sift through such documents and obtain a superficial, often slanted, and at times outrageous understandings of Latin America. Furthermore, such datasets are often funded by questionable U.S. governmental sources. Scholars, pressured to bring large sums of grant money to their universities, often rely on U.S. governmental institutions as a major source of funding, which is integral for maintaining research. All of these conditions can be problematic for research. Information that is cultivated under these conditions is often dominated by a U.S.-centric, English-based perspective. Latin American scholars have already expressed concerns about datasets for Latin America. Drawing upon Central America, Booth et al. point out that U.S. datasets “reflect the biases and fluctuating intensity coverage of the U.S. newspapers from which they are drawn and their manipulation by U.S. foreign policy makers.”[xx] What is written by intention in major U.S. newspapers, therefore, is crucial for the generation of new tranches of knowledge in both the academic as well as the public realm.

Dataset Comparisons

For the sake of comparison, I will briefly discuss three highly-cited datasets to highlight the main problems for Latin America and stress how the research presented here offers a more comprehensive, yet never complete, picture. They include Freedom House (FH), The Global Terrorism Database (GTD), and The Political Terror Scale (PTS).[xxi] Each dataset helps contribute to the understanding of democracy and terror, yet, for Latin America, there are serious shortcomings with such data. Created in 1941, Freedom House remains the oldest and most cited dataset related to world democracy. Funded by the U.S. government, FH has attracted a wide range of criticism. Despite being touted as an independent think tank, critics have longed accused FH of legitimizing regimes friendly to the United States and delegitimizing those that are not. Herman and Brodhead offered one of the first in-depth accounts of how FH served as a U.S. policy tool to legitimize questionable democratic elections in countries such as Rhodesia (1979) and El Salvador (1982).[xxii] Criticism is not limited to U.S. scholars. The former British ambassador in Uzbekistan (2002-2004) Craig Murray, for example, further confirms the prevalence of such multiple biases with Freedom House, noting how the organization ignored human rights abuses in the country since the Uzbek government was supporting the U.S. war on terror.[xxiii] Conversely, in an effort to delegitimize a country with which Washington has had tensions, FH relied upon opposition figure and former Contra member Arturo J. Cruz to report on democracy for Nicaragua in the 1980s. Cruz later admitted to being on the CIA payroll. In a complete reversal of his report, he also confirmed that the 1984 Nicaraguan presidential elections, from which he abstained, were fair and free. He acknowledged that he should have remained a principal opposition candidate, despite conceding he would have lost against the Sandinistas’ popularity.[xxiv] FH and the U.S. government, however, refused to recognize the elections since the Sandinista candidate Daniel Ortega had won with 67% of the votes.[xxv] It should be no surprise that research currently finds a strong link between FH and support for the Venezuelan opposition, opposed to remaining neutral.[xxvi] Despite offering in-depth literature and useful measurements for studying democracy, the intimate connection FH has had with U.S. policy goals remains a serious issue for objectivity in Latin America.

Following the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, research on terror has grown immensely. Housed at the University of Maryland, the GTD is an outgrowth of this interest, coding for terrorist attacks perpetrated by non-state actors. Funded directly by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice, it often offers a U.S.-centric understanding of what is considered terrorism. To the researchers’ credit, they have highlighted a number of U.S.-supported terrorist groups such as the Nicaraguan CONTRA and Miami Cuban organizations. Nonetheless, the database should remain suspect for scholars of Latin America; for it codes popular democratic movements, peasant organizations, and people simply trying to defend themselves as terrorists. These include the Nicaraguan Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), the broad-based guerrilla movement which successfully toppled the U.S.-supported regime of Anastasio Somoza Debayle (1967-1979). The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a broad-based movement of Salvadoran guerillas, is also coded as a terrorist group. In most cases, guerilla fighters were defending themselves against a very violent and repressive government.[xxvii] On the other hand, Nicaraguan and Salvadoran governmental atrocities, as well as non-governmental groups such as the infamous Salvadoran death squads (escuadrones de muerte), have been able to escape the “terrorist” label. The idea that the Salvadoran military can slaughter up to 800 civilians in the 1981 Massacre of El Mozote and not be coded as “terrorism,” but the peasants who defend themselves from such acts are should be met with great suspicion.[xxviii] Dora María Téllez, a prominent Sandinista guerilla who played an integral part in overthrowing the Somoza Dynasty (1936-1979), personally finds the GTSD coding for terrorism as offensive. She further stressed that those involved with the database harbored a rudimentary understanding of Central American politics.[xxix] Lamentably, the database appears to reflect Noam Chomsky’s perennial criticism of the academia of terrorism. For Chomsky, scholars and journalists readily label peasant groups terrorists while ignoring the terrorist acts of powerful actors such as the U.S. government. “The ‘terrorism’ of properly chosen pirates, or of such enemies as Nicaraguan or Salvadoran peasants who dare to defend themselves against international [U.S.] terrorist attack,” Chomsky points out, “is an easier target.” “The U.S. terrorist war in El Salvador is not a topic of discussion among respectable people; it does not exist,” he concludes.[xxx] Therefore, the database, yet valuable for understanding non-state attacks, fails to take into account the Latin American experience and, therefore, should remain suspect for students of Latin American politics.

Turning specifically to state-sponsored terror, PTS aims to be a sophisticated dataset on political terror.[xxxi] Using numerical scale from 1 to 5 (1 being the least amount of terror and 5 being the most), the researchers deserve accolades for bringing state terror and human rights to the forefront of scholarly debate. Despite operationalizing terror in a thorough manner and demonstrating a genuine interest in examining human rights, the dataset falls short by relying on two limited English-centric US-based sources: The Department of State and Amnesty of International. Despite having a wealth of information, both sources suffer from severe biases. First, the State Department is a politicized governmental entity aimed at supporting friends and delegitimizing enemies. Alexander L. George and Andrew Bennett remind scholars of the intrinsic problems when we rely solely on governmental archival data. “It is well known that those who produce classified policy papers and accounts of decisions,” George and Bennett point out in their widely-read book Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences, “often wish to leave behind a self-serving historical record.”[xxxii] This could not be truer than for Latin America, Washington’s “backyard.” The Department of State has developed reports on political violence, human rights, and democracy, in the words of Latin Americanist Lars Schoultz, as “no more than a propaganda weapon to be pulled out of a nation’s arsenal whenever strategic considerations indicated it would be useful.”[xxxiii] It is no wonder why democratic governments such as Bolivia under President Evo Morales Ayma (2006-present) is oddly coded as having more political terror than Bolivia under the brutal racist dictatorship of Hugo Banzer Suárez (1971-1978).[xxxiv] Amnesty International also suffers from serious weaknesses. Most importantly, critics of AI stress that the NGO’s proximity to both the United States and United Kingdom’s foreign policy interests has significantly affected its work.[xxxv] Despite its methodological value, PTS suffers from source limitations.[xxxvi]

The research presented here, however, advances a more thorough and unbiased dataset on political terror. First, this study was carried out with no external funding. Governmental preferences had no influence over the results. The goal is to find, in the words of famed sociologist Max Weber, “inconvenient facts” that may challenge one’s preconceived notions and/or interests.[xxxvii] But possibly more important, this work relies upon a wide range of open-source information in both Spanish and English and does not limit sources to U.S.-centric and English-based, as well as opposition-biased, reports.[xxxviii] Opposition sources such as the news outlet El Universal and the very anti-Chavista outlet Lapatilla.com are consulted. However, sources supportive of the Bolivarian Revolution such as Venezuelaanalysis.com are also used to balance the information. Sources considered middle-of-the-road (one example is the Venezuelan daily Noticias24.com) further helps make sense of the data. In the end, hundreds of sources in Spanish and English are consulted to develop a dataset that can be considered objective. The research here does not claim to advance a comprehensible end-all understanding of the Venezuelan crisis. Nonetheless, it does have significant advantages over the more politicized literature and datasets noted above. Results, presented below, are included to allow for a greater understanding, as well as data collection transparency, of the crisis.

Graph 1 Graph 2

Graph 3 Graph 4

Table 1: Political Violence by Government

| Date | Location | Act of Terror | Result | Level |

| February 12, 2014 | Caracas | Attack of student protesters by Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional (SEBIN) | Death of Bassil Alejandro Dacosta | High |

| Feb. 12 | Caracas | Attack of student protesters by SEBIN | Death of Robert Redman | High |

| Feb. 12 | Caracas | Attack of student protesters by SEBIN | Death of Juan Montoya, 53 (Chavista) | High |

| Feb. 13 | Caracas | Abuse of detainees by La Guardia Nacional Bolivariana (GNB) | Juan Manuel Carrasco makes official complaint of torture | Medium |

| Feb. 17 | Caracas | Three raid of Voluntad Popular’s (political party) office | Infringement of rights | Medium |

| Feb. 18 | Valencia, Carabobo | Attack of protesters by possible governmental supporters | Death of Génesis Carmona Diez (February 20th) | High |

| Feb. 18 | Caracas | Arrest of Leopoldo López for inciting coup | Leopoldo López imprisoned | High |

| Feb. 18 | Maracay, Aragua | Dispersion of seven-day protest by GNB and la Policía Nacional Bolivariana (PNB) | 18 wounded | Medium |

| Feb. 19 | Valencia, Carabobo | Dispersion of protest by GNB | Death of Geraldine Moreno Orozco | High |

| Feb. 23 | Caracas | Attack of protesters by GNB | Death of José Alejandro Márquez | High |

| March 8-9 | Las Mercedes | Early 3:00am dispersión of protest by the GNB and the PNB | 243 students detained | Medium |

| March 19 | Caracas | San Diego Municipality Mayor Vicencio Scarano Spisso (“Enzo”) sentenced to prison for not removing barricades | Imprisonment | High |

| March 19 | San Cristobal, Tachira

|

Arrest of San Cristobal Mayor Daniel Ceballos for inciting violence

|

Imprisonment

|

High |

| March 10 | San Cristóbal, Táchira

|

Shooting of student governmental supporters called “Colectivos” | Death of Daniel Tinoco | High |

| March 11 | Barquisimeto | Dispersion of student protesters by GNB | Six injured | Medium |

| March 12 | Valencia, Carabobo | Attack of student protesters by “Colectivos” | Death of Jesus Enrique Acosta and Guillermo Sanchez | High |

| March 19 | San Cristobal, Tachira | Dispersion of protesters by GNB | Two injured by GNB | Medium |

| April 18 | Chacao, Miranda | Dispersion of protesters by PNB | Two protesters injured | Medium |

| August 4 | San Cristobal, Tachira | Dispersion of protesters by GNB | Protester injured | Low |

| Sept. 1 | San Cristobal, Tachira | Dispersion of protesters by GNB | Six protesters injured | Medium |

| February 10. 2015 | Táchira | Dispersion of protesters by GNB | Three students wounded at la Universidad Católica del Táchira (UCAT). | Medium |

| Feb. 25 | San Cristobal | Dispersion of protesters by GNB | Death of Kluivert Roa Núñez | High |

Table 2: Political Violence by Opposition

| Date | Location | Act of Terror | Result | Level |

| February 12, 2014 | Caracas | Attack against Public Ministry with firebombs | 23 injured governmental workers | High |

| Feb. 12 to May 12 | Caracas, among other major cities | Attacks against over 100 metro buses with firebombs and other arms | Over 200 passengers injured | Very High |

| Feb. 12 throughout the year | Throughout Venezuela | Physical attacks against up to 162 Cuban doctors and facilities | Injuries against doctors include burning doctors and severe property damage | Very High |

| Feb. 15 | Chacao, Caracas and Los Teques, Miranda | Attacks against Ministries of Transportation with gunshots and firebombs | Property destroyed and people dispersed | High |

| Feb. 19 | El Paraiso, Caracas | Roadblocks | Death of Luzmila Petit de Colina because roadblock obstructed access to hospital | Medium |

| Feb. 20 | San Cristóbal, Táchira | Attacks using fire mortars and rocks against the home of Governor of Táchira Jose Gregorio Vielma Mora | No injuries, but 157 children from the Special Rehabilitation Center were inside. Police dispersed protesters, no arrests | Medium |

| Feb. 20 | Ujano, Gran Barquisimeto | Shootings against those removing protester barricades | Death of Arturo Alexis Martinez | High |

| Feb. 20 | Mérida, Mérida | Use of wire in protester barricade to block streets | Death of Delia Elena Lobo | High |

| Feb. 21 | Sucre, Miranda | Use of electrical wire in barricade to block streets | Death of protester Elvis Rafael Durán De La Rosa | High |

| Feb. 24 | Maracaibo, Zulia | Sniper shooting of National Guard while clearing protester barricade | Death of Antonio José Valbuena Morales after being shot in head | High |

| Feb. 24 | Cagua, Aragua | La entrada de la Urbanización la Fundación de Cagua | Death of Wilmer Juan Carballo Amaya | High |

| Feb. 25 | Valencia, Carabobo | Individual crashed into barricade | Death of Eduardo Anzola | High |

| Feb. 28 | Valencia, Carabobo | Attacks against the home of Nancy Pérez, the Minister for the Ministry of Regional Development in Los Llanos | Warnings by neighbors that if the Minister left home there would be bodily injuries by protesters | Medium |

| March 1 | Ayacucho, Táchira | Oil poured into Ayacucho street | Property damage | Low |

| March 3 | Rubio, Táchira | Collision into protester barricade | Death of Luis Gutiérrez Camargo | High |

| March 6 | Los Ruices, Maracaibo | Sniper shootings against members of National Guard cleaning after protests | Death of Acner Isaac Lopez Lyon | High |

| March 3 | Chacao, Miranda | Crash of motorist into uncovered manhole used by protester barricades | Death of Deivis José Duran Useche | High |

| March 6 | Los Ruices, Caracas | Sniper shootings of private citizens while cleaning after a protest | Death of José Amaris Cantillo | High |

| March 7 | Caracas | Motorist slipped in oil protesters spilled | Death of Johan Alfonso Pineda Morales | High |

| March 7 | El Hatillo, Caracas | Attacked telenovela stars Roque Valero, Kenyú Suárez, Jorge Reyes, and Alejandra Sandoval | No injuries reported but was threatening to the extent to which local police had to escort them and a baby out of the restaurant for safety. | Medium |

| March 10 | Colinas de Unare, Bolívar | Student leaders attacked by opposition | Death of Angelo Vargas and two injured | High |

| March 17 | Aragua | Sniper shot member of the National Guard while he was cleaning up after a protest | Death of José Guillén Araque | High |

| March 19 | Carabobo, Valencia | Member of the National Guard shot | Death of Ramzor Ernesto Bracho Bravo | High |

| March 22 | Mérida, Mérida | State communications entity Movilnet | Death of Juan Orlando Labrador Castiblanco | High |

| March 24 | Mérida, Mérida | Member of the National Guard | Death of Miguel Antonio Parra Sargento | High |

| March 27 | Girardot, Aragua | Library fire | Fire of the library in Girardot | Medium |

| March 29 | San Cristobal, Táchira | Member of the National Guard shot | Death of Jhon Rafael Castillo Castillo | High |

| March 29 | San Cristóbal,

Táchira |

Member of opposition electrocuted | Death of Franklin Alberto Romero Moncada | High |

| April 1 | Caracas | Ministry of Housing on fire with Molotov cocktails | 1,200 workers were inside the building and daycare center | High |

| April 4 | San Cristóbal,

Táchira |

Buses lit on fire | Fire in streets | High |

| April 9 | Lara | Member of National Police Shot | Death of José Cirilo Darma García | High |

| April 18 | Chacao, Miranda | Protesters clash with PNB | One police officer injured | Medium |

| May 5 | San Cristobal, Táchira | Bus operator burned almost to death | Bus and driver set on fire, severe burns | High |

| May 5 | San Cristobal, Táchira | Catholic University attacked. | Chairs and desks lit on fire in street over rector’s decision to re-open. | Medium |

| May 5 | San Cristobal, Táchira | State oil company truck attacked | Truck lit on fire | Medium |

| May 6 | San Cristobal, Táchira | National Guard Truck attacked | Truck lit on Fire | Medium |

| May 7 | San Cristobal, Táchira | Grenade launched into PDVSA Gas Comunal | Business exploded | High |

| May 8 | Los Palos Grandes del municipio Chacao. | Clearing barricadas attacked by sniper | Death of Jorge Steven Colina Tovar, funcionario de la Policía Nacional Bolivariana (PNB) | High |

| May 8 | Los Palos Grandes del municipio Chacao. | Residents clearing barricadas attacked by sniper | Tony Orlando Gil injured in neck by sniper | High |

| May 8 | Pie del Tiro, in the Andean capital of Merida | Resident clearing barricadas attacked | Death of Chilean Giselle Rubilar | High |

| May 8 | Pie del Tiro, in the Andean capital of Merida | Resident clearing barricadas attacked | Two other injured | High |

| May 20 | municipio Diego Bautista Urbaneja del estado Anzoátegui | Office of Cantv governmental truck set on fire | Fire in Cantv | Medium |

| May 20 | municipio Diego Bautista Urbaneja del estado Anzoátegui | Office of Banco del Tesoro in Lechería set on fire | Fire in the Banco del Tesoro in Lechería | Medium |

| June 3 | Valencia, Carabobo | Use of fire in the streets | Rubber tires on fire blocking highway | Low |

| July 17 | San Cristobal, Táchira | Firebombing police station | Destruction of 28 motorcycles and 4 patrol cars | High |

| Oct. 1 | Caracas | Intentionally murdered at home | Death of Robert Serra | High |

| Oct. 1 | Caracas | Intentionally murdered at home | Death of María Herrera | High |

| January 30, 2015 | Mérida | Church in Mérida fire bombed | Church on fire | Medium |

| Feb. 9 | a un costado de la Universidad Católica del Táchira (Ucat), en Barrio Obrero | CANTV vehicle fire bombed at la Universidad Católica del Táchira

|

CANTV vehicle on fire | Medium |

| Feb. 18 | Chacao | Venezuelan Air Sargent attacked | Air Sargent Luis Alejandro Linares Espinoza injured | Medium |

Table 3: Accidental Controversies

| Date | Location | Act of Terror | Result | Level |

| Feb 18 | Carúpano, Sucre | Student hit by truck | Death of José Ernesto Méndez | High |

| Feb 24 | San Cristobal, Tachira | Student fell off roof | Death of Jimmy Vargas | High |

Table 4: Coverage by New York Times

| Publication Date | Author | Act of Terror or Abuse | Attribution | Level |

| February 12, 2014 | W. Neuman | Two killed in peaceful protest. Protesters attribute killings to government and government to “fascist” protesters | N/A | High |

| Feb. 14 | W. Neuman | Two opposition protesters and one governmental supporter dead | N/A | High |

| Feb. 18 | W. Neuman | Opposition leader Leopaldo Lopez turns himself in to authorities after being charged with murder and terrorism; repression of protesters, media, Lopez’ political party the Popular Will | Gov | High |

| Feb. 18 | N. Kitroef

(blog) |

Leopaldo Lopez turns himself in to authorities | Gov | Medium |

| Feb. 20 | W. Neuman | Death of Genesis Carmona, death of protesters, repression against the media and protesters. | Gov | High |

| Feb. 20 | J. Preston

(blog) |

Death of Genesis Carmona | Gov | High |

| Feb. 21 | N. Kitroef

(blog) |

Media repression | Gov | High |

| Feb. 23 | W. Neuman | Death of Roberto Redman | Gov | High |

| Feb. 25 | W. Neuman | In Barrio Sucre, fired against woman and son; 2 killed in San Cristóbal at least 12 deaths | Gov | High |

| Feb. 25 | J. Preston

(blog) |

Repression of media | Gov | Medium |

| Feb. 26 | W. Neuman | Death of Jimmy Vargas and National Guard Attacks | Gov | High |

| Feb. 27 | E. Krauze

(opinion) |

Dictatorship | Gov | High |

| Feb. 28 | D. Waldstein

(Sports) |

New York Yankees players fear retribution against families | Gov | Medium |

| Feb. 28 | E. Krauze

(opinion) |

Economic mismanagement; corruption; repression; | Gov | High |

| March 1 | W. Neuman | Over a dozen deaths | Gov. | High |

| March 7 | D. Gonzalez

(blog) |

Country that is failing | Gov. | low |

| March 12 | W. Neuman | Death of Daniel Tinoco and Acner Lopéz | Gov | High |

| March 20 | W. Neuman | Imprisonment of Daniel Ceballos, the former mayor of San Cristóbal, and Vicencio Scarano Spisso, mayor of San Diego Municipality | Gov | High |

| March 26 | W. Neuman & V. Burnett | Abuse of protesters | Gov and Cuba | Medium |

| July 20 | L Alvarez | Fleeing political crises to Miami | Gov | Medium |

| July 25 | W. Neuman | Support for terrorists the FARC; drug ties | Gov | Medium |

| July 29 | W. Neuman | Drug ties | Gov | Medium |

| Aug. 7 | D. Lansberg-Rodríguez

(opinion) |

Press freedom stifled | Gov | Medium |

| Aug. 16 | E. Krauze

(opinion) |

Anti-Semitism | Gov | Medium |

| Sept. 14 | P. Oloixarac

(opinion) |

“Neo-socialist” use of technology to monitor people | Gov | Medium |

| Sept. 21 | W. Neuman | Imprisonment of Iván Simonovis (political prisoner) | Gov | High |

| Sept. 21 | Editorial Board | Repression of peaceful opposition and media. Imprisonment of Lopez. Despotic rule of Chavez and his successor Maduro | Gov | High |

| Sept. 22 | Ernesto Londoño

(blog) |

“Atrocious crackdown” against the opposition | Gov | High |

| Oct 21 | Ernesto Londoño

(blog) |

Crackdown against the opposition and “pro-democracy activists” | Gov | High |

| Feb. 20, 2015 | G. Gupta | Arrest of Caracas Mayor Antonio Ledezma | Gov | High |

| Feb. 21 | G. Gupta | More on the arrest of Caracas Mayor Antonio Ledezma | Gov | High |

| Feb. 22 | S. Romero & G. Gupta | Crackdown on dissident | Gov | High |

| Feb. 28 | W. Neuman | Detained missionaries | Gov | Low |

The New York Times and Empirical Analysis

From the beginning of 2014 to roughly the beginning of 2015, Venezuela experienced widespread protests, particularly in areas where opposition to President Maduro continues to have strong support. The opposition attributes the rise of protests to the government’s increasing authoritarian rule and mismanagement of the economy. For the opposition, Chavismo has politicized public institutions and led to economic disaster, creating scarcity and inflation.[xxxix] Supporters of Chavismo, on the other hand, attribute the aggressive protests to a number of other factors. First, they cite the failure of the opposition to make strong gains in the local elections following the close presidential race between Capriles and Maduro. Instead of being able to defeat Chavismo in the ballot box, “la Salida” (the exit) became the rallying cry for the violent protesters, most of whom are related to the now-imprisoned Leopoldo Lopez. Second, defeated presidential hopeful Capriles shook hands with Maduro, conceding defeat. The economy, which did not change from the election in the following years, serves as a pretext for initiating the violent overthrow of democracy and returning to the old ruling oligarchical elite.[xl] The NYT showed increasing interest in Venezuela when the protests emerged in earnest in the beginning of 2014.[xli] During the time period under study, the Venezuelan crisis was mentioned in thirty-three articles. Eighteen articles were international news stories with journalist William Neuman serving as the principal author for all but three. Girish Gupta, Simon Romero, Victoria Burnett, and María Eugenia Díaz were also contributors. The NYT did not limit its attention to the international section. The crisis appeared in one editorial, one national news story, five opinion pieces, and seven blogs. Venezuelan politics even emerged in the sports section. Two Venezuelan baseball players in the league threw in their support for the opposition protest. The question becomes, what do we really know about this time period in Venezuelan politics?

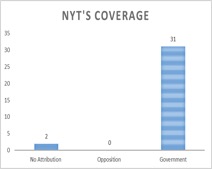

This research finds that the NYT accurately covered the political violence initially carried out by governmental entities. The Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional) (SEBIN) was involved in two notable acts of terror at the beginning of the crisis. On February 12th, 2014, members of SEBIN were responsible for the death of Bassil Alejandro Dacosta, a twenty-three-year old student and protestor. Almost immediately after Dacosta’s death, SEBIN utilized excessive violence again, leading to the death of Robert Redman, a thirty-one-year-old protester, on the same day. During the time under study, nine civilians were killed at the hands of the government or governmental supporters. The government committed further acts of terror through the violent dispersion of protesters and raids on the offices of opposition candidates. These acts often led to scores of injured protesters and the imprisonment of opposition figures Leopoldo Lopez, Vicencio Scarano Spisso, mayor of the municipality San Diego, and Daniel Ceballos, the mayor of San Cristóbal. As table 1 and Graph 1 demonstrate, out of the twenty-two acts of violence found, the majority, 55%, is coded as high. Medium and low acts of political violence compromise of 40.5% and 4.5%, respectively. Table 4 offers an in-depth view of the NYT’s coverage. The international and national news sections, opinion pieces, blogs, and an editorial covered the nine deaths, dispersion of the protesters, and the raids on opposition candidates, as well as other acts of violence such as the repression of media outlets and even the monitoring of people.

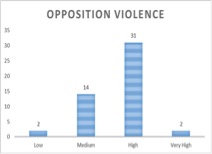

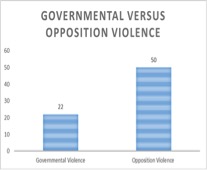

This research finds, however, that the NYT significantly underreported political violence perpetrated by the opposition. Despite two articles in which no attribution for violence is made, coverage exclusively focuses on governmental political violence and fails to report any damage or death attributable to the protesters (see both Table 3 and Graph 4). Despite this notable lack of coverage, the opposition committed the majority of political violence during the time under study[xlii]. Table 2 lists the political violence attributable to the opposition protesters and Graph 3 compares the amount of opposition violence to that of the government. Opposition violence makes up 69.4% of the overall political violence. Similar to the violence carried out by the government, the majority is coded as high at 68% (see Graph 2). Medium and low violence reflect 28% and 4%, respectively.

One of the most shocking series of deaths and injuries took place during the time in which neighboring residents and governmental officials tried to clear the demonstrators’ barricades (barricadas) that blocked the circulation of traffic. Barricades are a common sight during demonstrations in Latin America. [xliii] Sooner or later acting police officials and/or neighboring residents clear the areas to resume the normal movement of traffic. In the case of Venezuela, members of the opposition would return and use sniper fire to intentionally harm those removing the barriers. This form of violence took five lives and injured three. One noteworthy death was Chilean student and single mother Giselle Rubilar. The forty-seven-year-old was studying a master’s degree in education when she was shot helping remove a barricada in her neighborhood in the state of Merida. Giselle died a day later from her wounds in the hospital in the University of Merida. Two others were wounded with her.[xliv] Additionally, members of the Venezuelan National Guard and police force were killed or severely injured in this fashion. Opposition violence was not limited to attacking those clearing the barricades. Other acts of notable violence includes the use of arson. During violent demonstrations, protesters lit governmental buildings and transportation vehicles on fire, which led to property damage, bodily harm, and even death. The opposition also periodically attacked Cuban doctors, in some cases using arson. Since there are a number of documented cases is so high (162), this act of terror is coded as Very High.[xlv] The other Very High act of violence is also attributable to the opposition (see Table 2).

Since the vast majority of political violence is committed by the opposition, protesters are responsible for the majority of deaths. Of the thirty-one causalities found at the time, twenty-one is attributable to the opposition and ten to the government. Coverage also overlooked one of the most brutal and shocking acts of political violence: The death of Robert Serra and his partner María Herrera. Serra and Herrera were both brutally murdered at home in Caracas. Apart from a short Associate Press article that appeared on October 2, 2014, there is no indicative of an in-depth article of the mysterious and brutal deaths that shocked Venezuela. The youngest congress person ever elected in Venezuela, Serra was a rising star in Chavez’ wing of the socialist party and considered a popular candidate for a future presidential run. Evidence suggests that the murder was not a conventional robbery, but a political assassination.[xlvi] Former Colombian President (1994-1998) and Secretary of UNASUR (2014-present) Ernesto Samper stated, “The assassination of the young legislator Robert Serra in Venezuela is a worrying sign of the infiltration of Colombian paramilitarism”[xlvii]. Conversely, the NYT invested significant journalistic resources into covering the death of Alberto Nisman, the Argentine prosecutor suspiciously found dead under The Center-left government of Cristina Elisabet Fernández de Kirchner (2007-2015).[xlviii]

Lesser, yet notable violence was completely ignored. In one salient case that took place in early March of 2014, a trio of Telenovela stars and a female news presenter were attacked by opposition protesters. The incident later became known as the “cacerolazo.” While leaving the Caracas restaurant El Hatillo, Venezuelan actors Roque Dalton, Jorge Reyes, Venezuelan news presenter Kenyú Suárez, and Dalton’s Colombian actress wife Alejandra Sandoval found themselves trapped within the restaurant against their will for over three hours by violent protesters. Sandoval, who was hit a number of times, had to protect her young son during the incident. The stars were attacked for their sympathies toward Chavismo. They later gave emotional speeches at a rally with President Maduro.[xlix]

It is also worth noting that the NYT drew no attention to the counter protests and movements that continue to seek indemnification for opposition violence. Venezuelan cities were full of not only anti-governmental protests, but also pro-governmental ones as well. What is more, since the opposition protesters committed a great deal of political violence, a prominent group, the Committee of Victims of Guarimba Violence, developed to help those negatively affected. The group became famous for demanding indemnity far beyond Venezuela. Members have been presenting their case before the United Nations since 2014.[l] The NYT also drew no attention to the governmental responses to the excessive violence. The Venezuelan government tried and prosecuted up to eight officials for their participation in the death and injuries of protesters. In addition to failing to report so much surrounding protester violence, the NYT did not cover the extensive opposition violence that fell outside the demonstrations. In November of 2014, in the midst of the protests, the Association of Relatives of Assassination Victims (Asociación de Familiares de Víctimas de Sicariato – Asofavisi) among other activist groups protested against the roughly one hundred and seventy-eight killings of rural peasants by the hands of the wealthy landowner elite. ASOFAVISI collected seventeen thousand signatures to create a law protecting the peasantry from such acts of terror.[li] One hundred and seventy-eight is significantly more than the forty plus deaths that occurred during protests. As a result, it may not be how many are killed and wounded, but WHO is killed and wounded. Roughly six months later, peasant leader Roberto Carrera was assassinated in Carabobo State. Again, this incident was not reported by the NYT.

Implications

The data and results presented here do not suggest a conclusive and comprehensive understanding of the Venezuelan crisis. Despite developing thorough and rigorous datasets that were used to measure the extent to which the NYT covered Venezuelan politics over a period of time, future research and commentary is necessary. Nonetheless, the results strongly suggest a steady bias of media coverage for the time under study. The NYT focused exclusively on political violence carried out by the government and failed to cover any by the opposition. One unaddressed question inevitably emerges: Why would the NYT, one of the world’s most prestigious media outlets, offer such a lopsided view of events? The data collected in this research offer no special insight into why the NYT would fail to report opposition violence. But there is no shortage of theories explaining why mainstream new outlets tend to reflect a nation’s foreign policy interests. The most widely-cited and discussed theory continues to be Chomsky and Hermann’s “propaganda model,” developed in the 1988 book Manufacturing Consent. Countries that were considered “enemies” received unfavorable coverage, while friendly ones were given more favorable reporting. Fair and free presidential elections (1984) in Nicaragua (1984), a country the Reagan Administration (1981-1989) deemed hostile, attracted only negative coverage, whereas faulty elections in El Salvador (1982), a staunch anti-communist ally, drew positive reports.[lii] Additional research has confirmed mainstream media’s reflection of U.S. official policies. Drawing upon four U.S. newspapers (the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, LA Times, and USA Today), Desai et al. discover that the discourse on waterboarding is less likely to be referred to as “torture” when carried out by the United States. The researchers further find that from 1930 until 2004, when the waterboarding scandal broke, a shift took place in characterizing the act as torture. Instead, the word torture was rarely used and replaced with softer vocabulary such as “objectionable.”[liii]

Regardless of the reasons, the failure to report the opposition’s political violence has serious implications for how the outlined world interpret and understand the Venezuelan crisis because it distorts events in a number of ways. Most importantly, it creates and perpetuates a narrative in which the opposition is peaceful and the government is violent. The NYT’s coverage stresses a peaceful opposition throughout its coverage. The editorial piece, for instance, openly sides with the protesters, claiming that the opposition and López “peacefully called for Mr. Maduro’s resignation.”[liv] The results in this study, however, challenge the prevailing wisdom. The opposition has relied on a significant amount of violence, possibly more than the government itself. What is more, one must imagine if protesters in any major U.S. city relied on sniper fire to injure governmental police officials. The outrage in the United States would be harsh. No local, state, or federal government would allow this to take place. By failing to report not only opposition violence, but its brutality, readers fail to put governmental responses in context. Of course, this is not to exonerate governmental political violence. As coded, the government has carried political violence. Nor does this research exonerate the recent waves of violence from protests attributable to the closure of the National Assembly. However, the black-and-white analysis of peaceful opposition and violent government must be reassessed. Venezuelan politics, like that in any part of the world, are extremely complex. The study presented here is a modest step toward broadening our view and putting us in a better position to understand this very difficult and possibly misunderstood crisis.

By Charles Ripley, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Featured Image: Guarimbas Mural Taken From: Wikimedia

[i] See Paris Hilton’s Twitter account at https://twitter.com/ParisHilton/status/436457920923193344.

[ii] For a well-balanced understanding of the Bolivarian Revolution, see Margarita Lopez Maya, et al. Chavez: una revolucion sin libretto. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Auora, 2002.

[iii] Scholars in the social sciences have wrestled with the definition of political violence for decades. For the purpose of this research, I borrow from the conventional and long-standing definition Graham and Gurr advanced decades ago. Violence entails “behavior designed to inflict physical injury on people or damage to property.” Graham, Hugh Davis and Gurr, Ted Robert. Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspective (New York: Praeger, 1969), xxvii. Such bodily harm or property damage becomes political when it results from contentious political gain. The extensive work of Charles Tilly offers an in-depth understanding of political violence. For just one reference, consult: Tilly, Charles. The Politics of Collective Violence. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[iv]For recent criticisms of U.S. media coverage on Venezuelan politics, see the following: Boothroyd-Rojas, Rachael. “Can the NYT Really Answer Your Questions on Venezuela?” Venezuelaanalysis. Jan. 21, 2016. https://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/11828. Bolton, Peter. “Venezuela’s Outages and the Western Press’s Confirmation Bias Problem.” COHA, April 12, 2016. https://coha.org/venezuelas-outages-and-the-western-presss-confirmation-bias-problem/

[v]“Venezuela’s right-wing violence is ignored, say pro-government groups.” Al Jazeera. June 3, 2014. http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/6/3/venezuelaa-s-rightwingviolenceisignoredsayprogovernmentgroups.html.

[vi] Weisbrot, Mark.”The truth about Venezuela: a revolt of the well-off, not a ‘terror campaign.’” The Guardian. March 20, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/20/venezuela-revolt-truth-not-terror-campaign

[vii] It is crucial to note that there is no scarcity of research on media bias. Chomsky and Herman’s 1988 book Manufacturing Consent has become legendary for analyzing the media and foreign policy. More recently Desai et al. completed a study critical of U.S. coverage of torture. See Desai, Neal et al. Torture at Times: Waterboarding in the Media. Harvard Student Paper. April, 2010, 2 and 4. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/4420886.But what exactly is media bias? For this study, I rely upon the definition advanced by Matthew Baum and Yuri Zhukov. In a study on the international media’s coverage of the 2011 Libyan crisis, they define media bias as “the media’s tendency to systematically underreport or overreport certain types of events” (384).

[viii] Black, William K. Why Is the Failed Monti a ‘Technocrat’ and the Successful Correa a ‘Left-Leaning Economist’? Huffington Post. Dec. 9, 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/william-k-black/new-york-times-profile_b_2269009.html

[ix]“Venezuela doesn’t deserve a seat on the U.N. Security Council.” The Washington Post. Sept. 20, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/keep-venezuela-off-the-un-security-council/2014/09/20/1e23f01e-3dcd-11e4-b0ea-8141703bbf6f_story.html?utm_term=.c53a3cad14d0

[x] Birns, Larry, Mills, Frederick B., and Pineo, Ronn. “The Washington Post gets it Wrong About Venezuela.” COHA. Sept. 24, 2014.https://coha.org/the-washington-post-gets-it-wrong-about-venezuela/

[xi] Baum, Matthew and Zhukov, Yuri. “Filtering revolution: Reporting bias in international newspaper coverage of the Libyan civil war.” Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 3 (2015): 385.

[xii] Since the rise of Hugo Chavez, Venezuela has been the subject of intense political debate. One of the most colorful exchanges to develop is between actor Sean Penn, a vociferous supporter of Hugo Chavez, and his former co-star from the movie Colors (1988) actress María Conchita Alonso. Alonso, a Cuban-born naturalized Venezuelan citizen and vehement critic of Chavez, called Penn a “communist a-hole” in an informal heated exchange in LAX airport. Penn responded by calling her a “pig.” Bond, Paul. “Maria Conchita Alonso and Sean Penn Get Into Heated Shouting Match Over Hugo Chavez Comments (Audio).” The Hollywood Reporter. Dec 19, 2011. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/sean-penn-maria-conchita-alonso-hugo-chavez-275477)

[xiii] For a good example, see the NYTs’ Letter to the Editor by Oliver Stone, Mark Weisbrot, and Tariq Ali. “Oliver Stone’s Latin Film.” [Letter to the Editor]. New York Times. July 24, 2010. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0DE6D91F30F937A15754C0A9669D8B63

[xiv] In an article, the newspaper concedes that some coverage “was not as rigorous as it should have been” and “was insufficiently qualified or allowed to stand unchallenged.” “From The Editors; The Times and Iraq.” New York Times. May, 26 2004. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/26/world/from-the-editors-the-times-and-iraq.html?_r=0

[xv] The ad was published on Wednesday, September 9th, 2015 under The Truth About the Venezuela-Colombia Border Situation.

[xvi] For more on recent protests and the Constituent Assembly, see the following: “Venezuela crisis. What is behind the turmoil?” BBC, May 4, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-36319877. Pannell, J. “Examining the 8 million – An Analysis of Venezuela’s Constituent Assembly Vote.” COHA. Aug. 3, 2017. https://coha.org/examining-the-8-million-an-analysis-of-venezuelas-constituent-assembly-vote/.

[xvii] Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (2nd ed). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2013.

[xviii] Only two cases get the coding for “Very High.” The reason is the sheer number of victims that could have been coded individually: a.) over 100 metro buses firebombed with 200 injuries; and b.) up to 162 attacks against Cuban doctors throughout Venezuela.

[xix] The coding presented here can later be put in numerical form for regression analysis and agent-based modelling. For the purpose of this study, I draw upon simple descriptive statistics.

[xx] Booth, John A., Wade, Christine J. and Walker, Thomas. Understanding Central America. 5th ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008): 232.

[xxi] This is not to say there are no reliable datasets on Latin America. For a very in-depth and thorough dataset (based in Latin America) on the conflict in Colombia, see Jorge Restrepo, et al. “The Severity of the Colombian Conflict: Cross-Country Datasets versus New Micro-Data.” Journal of Peace Research, 43, no. 1 (2006): 99-115.

[xxii] Herman, E. and Brodhead, F. Demonstration Elections: U.S.-Staged Elections in the Dominican Republic, Vietnam, and El Salvador (Boston: South End Press, 1984).

[xxiii] Murray, Craig. Murder in Samarkand. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2006.

[xxiv] For the full interview and a deeper understanding of Cruz’ role in the 1979 Nicaraguan Revolution, see Stephen Kinzer. “Ex-Contra Looks Back, Finding Much to Regret.” New York Times. Jan. 8, 1988. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/08/world/ex-contra-looks-back-finding-much-to-regret.html.

[xxv] Krennerich, Michael. “Esbozo de la historia electoral nicaragüense 1950-1990.” Revista de Historia 7 (I). Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua, Universidad Centroamericana, Managua, 1996.

[xxvi] Bigwood, Jeremy. “Freedom House: The Language of Hubris.” NACLA (Summer, 2012): 59-63.

[xxvii] Atrocities carried out by the government of the Somoza Dynasty (1936-1979) and Salvadoran death squads are well-documented. For Nicaragua, see Booth, Wade, and Walker. 2006. For El Salvador, consult the following thinktank and book, respectively: Spence. Jack and Vickers, George. “Toward a Level Playing Field: A Report on Post-War Salvadoran election process.” Cambridge, MA: Hemisphere Initiatives, 1994. Wood, Elizabeth Jean. Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[xxviii] For in-depth coverage of the Massacre of el Mozote, see Danner, Mark. The Massacre at El Mozote. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1994.

[xxix] Téllez, Dora María. Interview with author, July, 2012.

[xxx] Chomsky, Noam. Pirates and Emperors, Old and New: International Terrorism in the Real World (New York: Haymarket Books, 2015): xix and 42.

[xxxi] To obtain a general understanding of PTS, see Wood, Reed M. and Gibney, Mark. “The Political Terror Scale (PTS): A Re-introduction and a Comparison to CIRI.” Human Rights Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2010): 367-400.

[xxxii] George, Alexander and Bennett, Andrew. Case Study and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2005): 101.

[xxxiii] Schoultz, Lars. Beneath the United States: A History of U.S. Policy toward Latin America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1998): 4. For more well-documented work on the U.S. and propaganda, see the following books by Schoultz: Human Rights and United States Policy toward Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981. National Security and United States Policy toward Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987.

[xxxiv] This is based on the aggregate Department of State terror scores of the tenure of each leader.

[xxxv] For general criticism, see former AI board member Francis Boyle’s interview in Dennis Bernstein and Dr. Francis Boyle” Discuss the Politics of Human Rights.” CovertAction Quarterly Summer (2002): 73, 9—12, 27. Related to Venezuela, see the following: Pearson, Tamara. “Amnesty International Opposes Venezuelans Defending Their Human Rights.” Venezuelanalysis. March 23, 2014. https://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/10524. Mallett-Outtrim, Ryan. “Amnesty International Whitewashes Venezuelan Opposition Abuses.” Venezuelanalysis. March 31, 2015. https://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/11304.

[xxxvi] The opinion here is that PTS could correct its weaknesses by diversifying its sources and including area specialists.

[xxxvii] The quote is lifted from William David Du Bois and Dean R. Wright. Politics in the Human Interest: Applying Sociology in the Real World. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books (2008): 15. See chapter 2 for a full description of Weber’s famous saying.

[xxxviii] This does not mean that the opposition does not get a say. Coding takes into account opposition sources such as el Universal and Tal Qual.

[xxxix] The online newspaper TalCualDigital.com, created by opposition figure Teodoro Petkoff, offers insight into how much of the opposition views the presidencies of Chavez and Maduro.

[xl] Sources sympathetic to the Bolivarian Revolution, such as Venezuelaanalysis.com and the U.S. think tank Center for Economic and Policy Research have communicated this interpretation of events.

[xli] It is worth noting that the articles were found through the LexisNexis online database and conventional online Google searches.

[xlii] The fact that the opposition committed the majority of violence is interesting in and of itself since many reputable sources attributed all the violence and death the government. See, for instance, Jairo Munoz. “Why China Should Worry About Venezuela.” The Diplomat. June 9, 2014. http://thediplomat.com/2014/06/why-china-should-worry-about-venezuela/.

[xliii] Living in Central America eight years, this became a noticeable motif in protests, regardless of ideology. Protesters would erect barriers in streets and civilians and governmental workers would later clear the roads when the protests calmed down.

[xliv] For more information, see Nicolás Sepúlveda. “El perfil bolivariano de la chilena que murió en Venezuela luchando contra las barricadas.” El Mostrador. March 10, 2014. http://www.elmostrador.cl/noticias/pais/2014/03/10/el-perfil-bolivariano-de-la-chilena-que-murio-en-venezuela-luchando-contra-las-barricadas/.for more information.

[xlv] For attacks on Cuban doctors, see José Manzaneda. “162 Attacks on Cuban Doctors in Venezuela Ignored by Media.” Venezuelanalysis. April 28, 2014. https://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/10651.

[xlvi] For more on Serra’s death and its relations with Colombian paramilitares and the Venezuelan opposition, see the following Frederick B. Mills (2014, Oct. 9). Aftermath of the Assassinations of Robert Serra and Maria Herrera. COHA. Oct. 9, 2014. https://coha.org/aftermath-of-the-assassinations-of-robert-serra-and-maria-herrera/. Koerner, L. Thousands March to Commemorate Anniversary of Venezuelan Legislator’s Assassination. Venezuelanalysis. Oct. 1, 2015. https://venezuelanalysis.com/news/11538.

[xlvii] “Venezuela: the disturbing message of Robert Serra’s murder.” The Guardian. Oct 9, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/09/venezuela-disturbing-message-robert-serra-murder.

[xlviii] Through a search on LexisNexis Academic, up to forty-seven articles were found to be covering the story. Only one AP article was found on the death of Serra.

[xlix] For more on the incident and the speeches, watch Roque Valero, su esposa, Jorge Reyes y Alejandra Sandoval hablan sobre en cacerolazo en El Hatillo. (2014, March 8). YouTube [videofile]. March 8, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q356rsI1X6A.

[l] Little has been written on the Committee, apart from local newspapers. For developments on its relations with the United Nations, see the following: Francisco Alonso, Juan. “Víctimas de las guarimbas exigen a la ONU que las escuche.” El Universal, Dec. 2, 2014. http://www.eluniversal.com/nacional-y-politica/141202/victimas-de-las-guarimbas-exigen-a-la-onu-que-las-escuche. “‘Víctimas de las guarimbas’ entregan informe ante ONU.” Globovision. April 19, 2016. http://globovision.com/article/victimas-de-las-guarimbas-entregan-informe-ante-onu.

[li] “Agricultores proponen ley contra el sicariato.” ÚltimasNoticias. Nov. 20, 2014. http://ve.noticiasol.com/ultimas-noticias/agricultores-proponen-ley-contra-el-sicariato.html.

[lii] Chomsky, Noam. and Herman, Edward. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

[liii] Desai et al. Torture at Times, 2 and 4.

[liv] “Venezuela’s Crackdown on Opposition.” [Editorial]. New York Times. Sept. 20, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/21/opinion/sunday/venezuelas-crackdown-on-opposition.html?_r=0