The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Free Trade at What Costs?

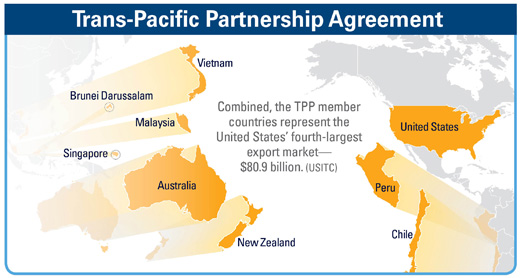

- The United States, Australia, Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam will meet next month for the 14th round of negotiations surrounding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)

- The TPP will encompass far more than trade, rewriting numerous domestic laws regarding, among other topics, intellectual property rights, investment, and environment protection throughout the region

- The TPP will also permit private foreign companies to sue sovereign countries on grounds of restriction of trade, thus supporting greater investor-to-state litigation

- A dearth of transparency has plagued the negotiations; beyond leaked texts and vague statements, few outside the negotiating room know anything about the details of the TPP

In November 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced Washington’s official pivot to Asia. Outlining a vision for an Asia-Pacific Century, Secretary Clinton described a desired symbiotic and unfettered relationship between the two regions that will provide “unprecedented opportunities for investment, trade, and access to cutting-edge technology.”[1] Washington hopes this engagement will help in “strengthening bilateral security alliances, deepening working relationships with emerging powers, engaging with relational multilateral institutions, expanding trade and investment, forging a broad-based military presence, and advancing democracy and human rights.” With the TPP as a first step, the ultimate goal is to “build a web of partnerships and institutions across the Pacific that is durable and consistent with American interests and values.”

At the center of this pivot has been the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an enigmatic trade pact that has been hailed as a true “21st century agreement.”[2] In negotiation since 2008, the TPP would link the United States with Australia, Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam (the TPP-9) across a variety of economic platforms. Mexico, Canada, and Japan are all looking to join the agreement (the TPP-12), which would make the TPP the largest trade bloc in the world, encompassing some 700 million people and about $26 trillion USD in various forms of economic activity.

But, for the most part, the member countries have conducted negotiations for the TTP under the mantle of utmost secrecy. The true scope of the agreement has only become apparent due to a few leaked texts and sporadic reports from the signatory countries. Evidently, trade is only the beginning of the TPP’s jurisdiction as it also contains chapters on customs, cross-border services, telecommunications, government procurement, competition policy, cooperation and capacity building, investment, financial services, environmental regulations, and intellectual property rights.[3] The very breadth of the agreement would require the rewriting of numerous domestic laws in every signatory country, threaten the sovereignty and autonomy of domestic legal systems, enable environmental degradation by transnational corporations, impose harsh patent regulations, and severely limit access to information across the globe. However, the most significant issue regarding the TPP is the very lack of transparency. Hailed as a new century trade agreement, the lack of information made available to the public, including the U.S. Congress, hardly embraces the realities of the twenty-first century. Ultimately, it is evident that the TPP has the power to transform the global economy and the Pacific community alike, with serious ramifications, both positive and negative, throughout the region.

Trade and Agriculture

Although the initial goal of the TPP was the promotion of free trade, only 2 out of 26 chapters concern this subject. The countries involved stand to benefit from lower prices resulting from fewer barriers to trade, but damage to the livelihoods of many workers appears to be inevitable. In 2011, the TPP-9 generated a GDP of $17.8 trillion USD, with the United States contributing 85 percent of this figure. Approximately 5 percent of U.S. trade flows are to its fellow TPP-9 countries; in 2011, U.S. exports totaled $105 billion USD to these countries while imports reached $91 billion USD.[4] The addition of Japan, Mexico, and Canada would bring both the combined GDP to $26.6 trillion USD and the TPP’s share of U.S. trade flows to 40 percent.[5] The TPP in its current form is estimated to augment the U.S. economy by $5 billion USD by 2015 and $14 billion USD by 2025, but this figure would drastically increase under the potential TPP-12.[6] These fiscal benefits would be far less for the U.S. than for other of its partners as Washington already has signed free trade agreements with Australia, Canada, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, and Singapore. Nevertheless, the U.S. hopes that this agreement will help it pivot its focus toward Asia politically by means of this regional forum, as well as economically by tapping East Asia’s increasing large disposable income.

Agriculture primarily drives regional trade and governmental control over domestic agricultural sectors will be significantly impacted by the TPP. Canada, in particular, is concerned about the mandate that would force Ottawa to alter its supply management policy that presently protects approximately 15,000 dairy and egg farmers. This action would effectively neutralize the industry on the world market because they would not be able to compete against cheaper goods coming from Australia and New Zealand. The OECD estimates that Canadians spend an additional $3 billion USD on food products annually as a result of Canada’s supply management policies.[7] Despite these concerns, Canadian Prime Minister Steven Harper reiterated his eagerness to join negotiations at the June G20 summit in Los Cabos, declaring, “This is a further example of our determination to diversify our exports and to create jobs, growth and long-term prosperity for Canadian families,” especially because Canada lacks FTAs with East Asian countries.[8] Canada’s dairy supply management program is only one a number of policies practiced throughout the region that would detract from the benefits of free trade and manipulate the agreement to benefit domestic interests.

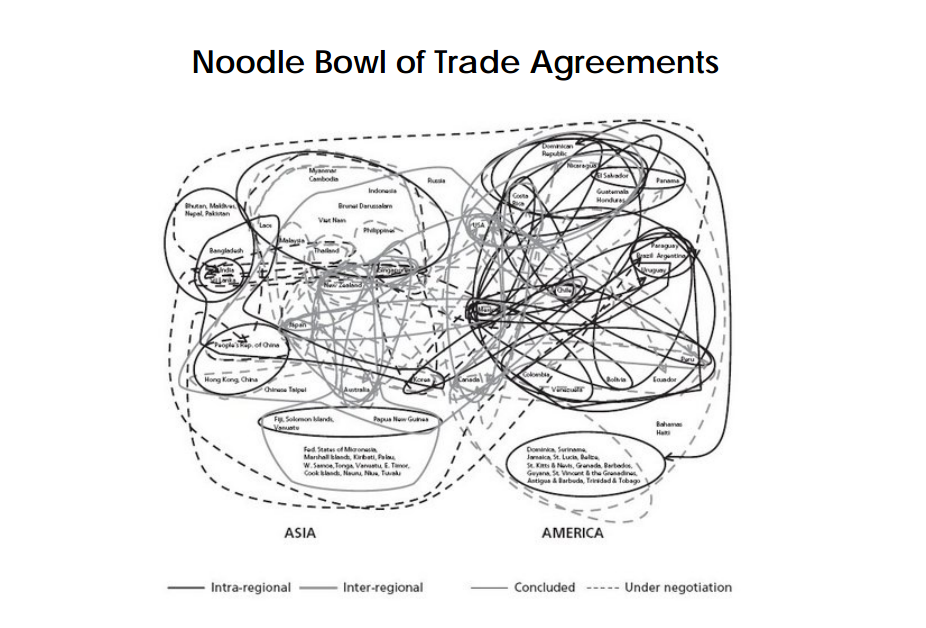

Nevertheless, there is no question that the TPP as it now stands would benefit regional trade. As Laura Dawson, an expert on Canadian trade relations explained, the number of regional alliances and FTAs complicates transactions and creates a “noodle bowl” of international trade, one that increases the cost of exportation by an average of 5 percent.[9] Consolidating the restrictions and regulations under one agreement would help cut down these costs, hopefully inducing further economic integration. With billions of dollars in potential gains, this integration is what truly generates interest in specific countries and points to what could be the most salient benefit from the TPP.

Transparency

The major concerns regarding the TPP surround the dearth of transparency provided by signatory countries. At the beginning of the negotiations, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) issued a statement declaring that the TPP is an “ambitious, next-generation, Asia-Pacific trade agreement that reflects U.S. priorities and values.”[10] President Obama’s own endorsement stated that the TPP will “boost our economies, lowering barriers to trade and creating more jobs for our people.”[11] But beyond these vague declarations, no one outside of the negotiators’ inner circles has been allocated detailed information regarding the treaty. Indeed, the public probably knows more about the defense budget and the aggregate deployment of U.S. nuclear warheads than it does about the U.S. position on the TPP.

In the recently concluded 13th round of negotiations in San Diego, the USTR invited 300 registered stakeholders to participate in a “Stakeholder Engagement Forum;” however, save for the cleared advisors—primarily industry representatives—few “had any clue what was really going on.”[12] As David Levine, an associate professor at Elon University School of Law and one of those invited to attend the forum, reflected, “The only thing that I knew with certainty was that I didn’t know much about what was happening in the TPP negotiations, and therefore I couldn’t offer much in the way of substantive questions and input.” Levine also signed an open letter from law professors around the world to USTR Ambassador Ron Kirk, which argued that the USTR must improve transparency in the negotiating process if indeed the goal is “to create balanced law that stands the test of modern democratic theories and practices of public transparency, accountability, and input.”[13]

Not even Congress effectively has participated in the TPP negotiation process. On June 27, 132 members of Congress petitioned Ambassador Kirk to “provide [them] and the public with summaries of the proposals offered by the U.S. government.” They pushed the USTR to adopt a similar approach as during the Free Trade Area of Americas (FTAA) negotiations, when drafts of the text were released to Congress and the public.[14] In a largely symbolic move, Senator Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced a bill that would require the White House to distribute TPP documents. His calls have been mirrored by congressmen from both sides of the aisle; as Senator Richard Burr (R-N.C.) declared: “When our staff requested to review the TPP on behalf of the senator, even staff with what we consider to be appropriate clearance were denied.”[15]

Clearly, these closed-door negotiations do not resemble the White House’s vision of the TPP as a “21st century trade agreement.” Alarmingly, the President noted that the TPP was supposed to become “a high-level trade agreement that could potentially be a model, not just for countries in the Pacific region, but the world in general.”[16] However, the Obama Administration is not embracing the realities of the modern informative network, setting a detrimental precedence for such an important agreement. The USTR claims that this has been the most transparent FTA to date. Yet the USTR also argues that the TPP is not simply an FTA, but rather an international agreement in which trade is only one element involved in the negotiations. In this respect, the TPP has not lived up to the precedent set in such negotiations as the FTAA or in organizations such as the Asian Pacific Economic Community (APEC). Indeed, beyond any substantive concerns regarding the text of the TPP, the lack of transparency might be the most troubling aspect of the proposed pact.

Investment Chapter[17]

In a 2008 campaign speech, President Obama promised: “We will not negotiate trade agreements that stop the government from protecting the environment, food safety, or the health of its citizens; or give greater rights to foreign investors than to U.S. investors.”[18] Almost every provision promised in this speech has been violated by the TPP proposal, primarily in the recently leaked investment chapter. This chapter has become particularly contentious even within the sealed negotiations with Australia refusing to sign the provision. Using a broad definition of investment, provisions contained in the chapter will enact international laws that will protect anything from existing investments by domestic firms in foreign countries to shares and derivatives, public-private partnerships, mining and manufacturing licensing and permits, as well as expected future profits of other TPP investors. Therefore, the chapter defines investment far beyond the traditional bounds of real property.

The investment chapter threatens the national sovereignty of signatory nations due to the creation of an arbitrary international tribunal that could bypass domestic laws when it comes to ruling on investor-to-state disputes. This tribunal follows the trend of treaties subordinating the role of national legal systems in dispute resolutions. Thus, if an investor believes that a law, regulation, policy, or program in a foreign country has violated his or her rights—even if the foreign government implemented those laws for the welfare of its citizenry—the investor can sue the foreign government for compensation in an international tribunal.[19] As B.S. Chimini argues, “it is not the greater internationalization of interpretation and enforcement of rules that is problematic but its differential meaning for, and impact on, third world states and people.”[20] Over $350 million USD have been paid out by governments to corporations in these investor-state cases, such as the one between Renco and the Peru (detailed later), which attack anything from natural resource policy to health and safety measures.[21]

Because the TPP removes the host state of the foreign investors from litigation, investors would be capable of exploiting loopholes such as Most Favored Nation (MFN) status or utilizing the broad definition of indirect expropriation to pick advantageous standards and dispute settlement mechanisms.[22] These investor-to-state negotiations will enable transnational corporations to reap profits from foreign citizens over policy in the countries where the corporations operate, even when no international state-to-state disputes exist.

Intellectual Property Chapter[23]

The intellectual property chapter appears to carry with it the most substantive changes to international law to be found in the entire TPP. A leaked text, available via House Oversight Committee Chairman Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), details a harsh copyright law, mirroring that of the United States, which has the potential to alter domestic laws throughout the region. This chapter, driven primarily by the U.S., if adopted in its current state, would enact the strongest intellectual property protection and enforcement standards in any FTA to date. The proposed document embraces the controversial Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) and recalls the rejected Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), pushed by the powerful pharmaceutical and Hollywood-funded lobbying firms in Washington, by altering the ability to access information and vital resources for developing countries. The primary issues in the intellectual property chapter surround the extension of copyright, restriction of parallel importation, the enforcement of new laws, and the ramifications for such products as textbooks and medicine. The intellectual property chapter best exemplifies the maximalist stance Washington has taken in these negotiations, which contradicts the development agenda proposed in more transparent, multilateral agreements such as the 1994 WTO Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement (TRIPS).

In terms of copyright, the TPP will dramatically expand its minimum international standards in scope and length, many of which do not even reflect settled U.S. law. The treaty proposes to lengthen copyrights on published works; under the treaty they would expire 70 years after the death of the author or no less than 95 years from the first authorized publication. This would extend the length of copyright in a significant portion of signatory countries as well as annul the TRIPS standard of 50 years after death or 50 years after publication. Although this copyright period mirrors U.S. law, the U.S. law sets 70 years post-mortem as a ceiling, while the TPP denotes this as a minimum length. These extended laws go against economic rationality, as the government cannot incentivize the creation of work that already exists under copyright, thus it draws no additional economic benefits. Rather, the extended laws would cut supply in the creative goods sector, particularly in developing countries where the public domain plays an increasingly important role in information dissemination.[24]

The intellectual property chapter further enables the patent or copyright holder to block parallel importation of copyrighted works. Parallel importation is the practice of importing a legitimate copyrighted good, not an illegal reproduction, at lower prices than what is available domestically without the permission of the copyright holder.[25] Many of the smaller TPP countries benefit from this practice because they lack the sufficient population or demand to attract a low market entry price. For example, with the TPP in effect, a school in Malaysia or Peru would be forced to purchase textbooks at higher domestic prices rather than contracting with a buyer who could purchase the textbooks at a lower price in a market such as the United States and then sell them to the school at the lower price. The restrictions on parallel imports remain unsettled or unenforced in every TPP signatory nation, including the United States. The current international laws surrounding this practice, denoted in TRIPS, leave countries free to adopt their own policies based on their domestic intellectual property laws.[26]

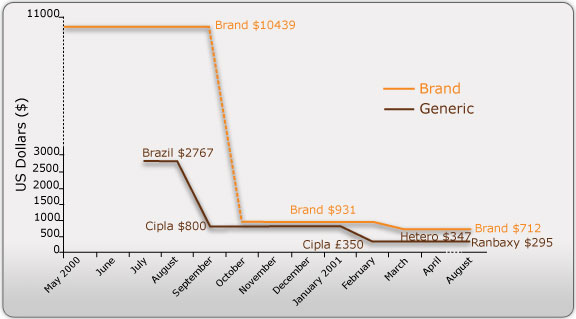

Another area where the proposed TPP text threatens domestic laws and the pre-existing international intellectual property framework involves the easing and expansion of patentability standards. The TRIPS provision only allows for additional patents on a product or process if the addition has industrial applicability or alters the function of the product.[27] The TPP, however, would allow additional patents for any new form, use, or method of utilizing an existing product, even if no applicability or efficiency measure exists.[28] Where this technique, known as evergreening, is most applicable is within the competing pharmaceutical and generic medicine industries. As Doctors Without Borders argued, evergreening allows major pharmaceutical companies to extend monopoly protection by making slight alterations to existing formulas, delaying the arrival of a more affordable generic version.[29] The first generation of HIV antiretroviral drugs, in 2000 shortly before the patent expired, cost an average of $10,000 to $15,000 USD per person per year—far outside the means of an average person living in a developing country. However, by 2011, the price of a similar generic drug combination had fallen to merely $60 USD per person annually.[30] Under the current intellectual property chapter of the TPP, such a devaluation process would take far longer, keeping these important innovations in health care out of developing countries in exchange for greater profits for the major pharmaceutical companies. This provision further contradicts President Obama’s position on refusing to negotiate trade agreements that “prevent developing country governments from adopting humanitarian licensing policies to improve access to lifesaving medications.”[31]

The final area of concern in the proposed intellectual property chapter is the enforcement aspect of copyright infringement. The U.S. has proposed a multi-faceted scheme for patent violations that allows for prosecution based upon pre-existing or statutory damages, a provision that appears in U.S. law, but not in that of any other signatory nation. This part of the TPP proposal takes the ability to punish infringers one step further by allowing for the prosecution of every infringer, rather than only willful ones.[32] This provision encourages a rent-seeking behavior on patent filing and deters innovation, both of which could prevent advances beneficial to social and economic development.

Environmental Regulations and Ramifications

Many U.S. environmental groups, in particular the Sierra Club, have expressed both concerns and hopes over the potential ramifications of the TPP.[33] U.S. negotiators have allegedly been pushing for stronger environmental regulations in the agreement, particularly regarding illegal logging, wildlife protection, and overfishing. But many other aspects of the TPP have the potential to damage the environment due to increased rights of corporations as well as the sweeping definition of investment.

The TPP would likely allow for increased exports of liquid natural gas with fewer regulations. This would undoubtedly result in an increase in hydraulic fracturing, a process that results in substantial environmental degradation, in order to obtain more natural gas. Hydraulic fracking threatens the environment and human health through water and air contamination, the migration of poisonous gases and chemicals to the surface, and the mismanagement of hazardous waste.[34]

Moreover, the aforementioned investment chapter stipulates that under the TPP, corporations will have the ability to sue governments over any piece of legislation or regulation that they perceive as damaging to their future profits. Many worry that this will allow corporations to challenge domestic laws protecting the environment. Under the U.S.-Peru FTA, U.S. mining company Renco was able to sue the Peruvian government for $800 million USD in damages following the denial of their request for a third extension for their obligated chemical clean up.[35] Under the TPP, lawsuits such as this one would likely become more common and would be resolved by foreign tribunals with rotating judges.

The TPP may also allow for corporations to challenge “preferential” labeling because such stringent standards on labels could result in favoritism towards a certain country’s product, therefore violating the FTA. This provision could result in more cases like the WTO ruling that forbid the U.S. from labeling tuna fished in a manner that prevented harm to marine mammals as “dolphin safe,” because it “unfairly discriminated” against Mexican tuna that was not required to feature this label.[36]

In May 2007, due to concerns that FTAs were opening up the potential for multinational corporations to damage to the environment, Congress arrived at a bipartisan consensus that all future trade agreements would include enforceable environmental chapters.[37] The TPP will undoubtedly include such a chapter. In FTAs with countries that are participating in the TPP, the U.S. already has shown some commitment to strengthened environmental standards. For instance, the U.S.-Peru FTA aimed to reduce illegal logging, a leading cause of deforestation.[38] Although there is the potential to help the environment through free trade agreements such at the TPP, profits often outweigh environmental concerns.

Latin America and the TPP

In recent years, Latin American and Asian markets have become increasingly intertwined through trade networks. In 1990, 60 percent of Latin America’s trade was with the U.S. and only 10 percent was with Asia while in 2012 those figures are markedly different.[39] In recent years, East Asian economies have invested heavily in the greater Latin American region and as a result many Latin American countries are striving to gain greater political and economic connections to East Asia. The TPP would facilitate such connections, making the agreement important for Latin American countries. Nevertheless, with its explicit focus on the United States and Asia, Latin America is only approached by little better than proxy in this agreement, which as a result has negatively affected perceptions of the pact around the region. As of now, Chile, Peru, and Mexico are the only three Latin American countries currently in, or seeking membership in, the TPP.

Chile, one of the original TPP members, already has enacted FTAs with a number of TPP countries including Australia, Mexico, the U.S., and Peru. Therefore, Santiago has recently expressed concern that it would receive minimal benefits from the TPP. Santiago takes issue with Washington’s strong stance on intellectual property issues, as current Chilean trade negotiator Ana Novik acknowledged, “We are not just negotiating with countries with high IP standards. This agreement needs to reflect that. We will not sign the TPP no matter what comes out of the process.”[40] This change in attitude has worried TPP supporters because Chile was long considered a guaranteed signatory. However, many in Chile who still support the TPP believe that the agreement will provide the country with greater access to TPP markets in addition to providing a multinational enforcement authority. Chilean ambassador to the U.S. Arturo Fermandois claimed, “We needed to integrate [with] the world” and views the TPP as the best manner in which to do so.[41]

Under President Alan Garcia’s second term from 2006 to 2011, Peru pursued a variety of free trade agreements including ones with the U.S., Canada, Singapore and China. Due to these already forged connections in the TPP region, similar concerns over the dearth of potential trade benefits exist in Lima. But, Peruvian Ambassador to the U.S. Harold Forsythe has remained optimistic, stating, “Peru is the main door for entry into Latin America for economies in the Asia-Pacific,” and thus will benefit from increased trade and economic opportunities under the TPP.[42]

The TPP members welcomed Mexico into the talks in June, much to the joy of departing president Felipe Calderon. Calderon believed that, “[The TPP] is one of the free trade initiatives that’s most ambitious in the world and would foster integration of the Asia Pacific region, one of the regions with the greatest dynamism in the world.”[43] But many in Mexico view the TPP as a modernization of NAFTA, whose significant contributions to economic growth were overshadowed by the havoc it wrecked on the livelihoods of farmers and other Mexican workers. Further, many in Mexico City have criticized the conditions of entrance for Mexico. Washington has encouraged Mexico to sign ACTA, an act with large-scale opposition in Mexico, and Mexico will have to accept any provisions already negotiated in the TPP because the negotiating table will not be reopened.[44] But Mexico fears potential ramifications for not participating in the TPP, in terms of trade with the NAFTA region, investment by East Asian countries, as well as the benefits of potential future expansion to Japan, South Korea, and China, so Mexico City has appeared to accept the harsh conditions.

Future Expansion

With the Doha Round of the WTO stalled, many view the TPP as the next step toward opening up and regulating international trade. The TPP could serve as a pathway to the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), which would also include other Asian powers such as South Korea and China in addition to the TPP-12. The addition of further countries, particularly large economies such as Japan, South Korea, and China would greatly increase the impact and importance of the TPP. These three countries in particular have recently shown great interest in Latin America, with China investing $15 billion USD in 2010 in the region, mainly in Brazil, Peru, Chile, and Mexico.[45] In 2011, Japan surpassed that investment figure, displacing China as the region’s top Asian investment and trade partner. Thus a possible TPP-12, or even TPP-14 with South Korea and China, would make the agreement much more attractive to Latin American countries. But significant obstacles will have to be addressed before any of these countries are able to join.

Much to the excitement of the U.S., Japan signaled its interest in joining the TPP talks last November but has balked regarding its formal application due to opposition in Tokyo. Washington welcomes the possibility of Japan joining the TPP because it hopes that the removal of Japanese protectionist policies will shrink its $62.2 billion USD trade deficit with Japan.[46] Concerns have risen over Japan’s highly protectionist agricultural sector as well as its auto industry. The rapidly aging Japanese farming population generally resides on small-scale farms and most farmers now receive a large portion of their income from nonagricultural sources. In terms of the staple of rice, Japan cannot compete with rice-producing bastions such as Vietnam, and instead resorts to absorbent tariffs that all but eliminate foreign supply of rice in the domestic Japanese market.[47] The cost that Tokyo incurs from protecting this industry with tariffs exceeds the value of production. Thus, removing the protections on Japanese farms would undoubtedly destroy the industry in its current form, but could spur a rapid modernization of the Japanese agricultural sector.[48] Similar controversy surrounds the auto industry, which uses import regulations to suppress the flow of American autos into the domestic market.[49] Many of the TPP-9 would like to see Japan admitted to help open up the economy to foreign products and services, ending this post-World War II era of protectionism.

Although South Korea remains more focused on developing free trade agreements within Asia, Seoul has been contemplating the possibility of joining the TPP. Seoul feels that the recently signed KORUS FTA as well as FTAs with other TPP-9 countries has bought it enough time that it can sit out the initial rounds of negotiations.[50] Thus, although Seoul currently is focusing on regional integration, as exemplified by the proposed Japan-China-Korea FTA and the recently opened China-Korea FTA, South Korea remains the most likely next step for future TPP expansion after the TPP-12.

Beijing has viewed the TPP with significant suspicion, with some detractors considering it to be a cross-continental trade agreement that intentionally excludes China in order to check its economic growth. Similar to Seoul, Beijing has focused on regional integration and has pushed ASEAN to expand to ASEAN+3, which includes China, Japan, and Korea.[51] Although no invitation is required to join the TPP and countries simply must meet its guidelines, China would most likely face difficulties achieving and maintaining those standards. Beijing’s policy of sustaining state run enterprises, the difficulties surrounding land purchase in China, the Chinese Central Bank’s intentional undervaluation of the currency, and various barriers to free trade all violate the principles of the TPP. Therefore, China’s addition would be seen as a massive asset, but one that would only be possible in the long term.

Conclusion

The Trans Pacific Partnership, which began as a modest trade pact between Singapore, New Zealand, and Chile, has the potential to alter existing global economic relationships. This so-called trade pact of the future covers far more than just trade, with chapters addressing modern topics such as an extension of investment past real property, intellectual property rights, and environmental standards among others. There is no question that the agreement would positively affect many signatory nations’ economies; however, many of the proposed regulations pushed by the U.S. would violate regional domestic laws while compromising national sovereignty. Most significantly, these regulations would contradict promises President Obama has made regarding trade negotiations and uphold the investor-to-state relationships that place the interests of big business ahead of those of the general citizenry.

Although this trade pact addresses many facets of international economic relationships, negotiations suspiciously have been conducted behind closed doors. The incredible dearth of transparency does not adequately represent a 21st century agreement, but rather one of the Cold War era, shrouded in secrecy. The secrecy prevents both dialogue in the general public through academic and policy organizations alike as well as citizens from expressing their opinions to elected leaders. Importantly, without this greater transparency, it is difficult to ascertain many implications of the pact.

As a centerpiece of President Obama’s pivot to Asia, which includes Latin America via the TPP, the trade pact sets a powerful, if not potentially dangerous, precedent for future trade agreements in the emerging region. But instead of encouraging sustainable economic trends and responsible transnational relations, the TPP could enact the same policies that have been proven detrimental in past smaller-scale agreements like NAFTA. The TPP rhetoric misrepresents the potential of free trade as it encourages, through greater international regulations, such as those seen in the intellectual property and investment chapters, the creation of domestic policies to manipulate the international market. Often, these actions strengthen the economically powerful, particularly by granting to the leadership the right to set its own nation’s course of action and implement its own visions, while those at the margins suffer. Thus, the TPP presents a troubling case of free trade being purchased at too great a price.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

[1] Clinton, Hillary. “America’s Pacific Century.” Foreign Policy (November 2011).

[2] “The Trans-Pacific Partnership Leaders Statement.” The Office of the United States Trade Representative. November 12, 2011. http://www.ustr.gov/about-us/press-office/press-releases/2011/november/trans-pacific-partnership-leaders-statement.

[3] “Important Progress Made at TPP Talks in San Diego.” The Office of the United States Trade Representative. July 10, 2012. http://www.ustr.gov/about-us/press-office/press-releases/2012/july/important-progress-tpp-talks-san-diego

[4] “The Significance of the Trans-Pacific Partnership for the United States.” The Brookings Institute, May 16, 2012. http://www.brookings.edu/research/testimony/2012/05/16-us-trade-strategy-meltzer

[5] Ibid.

[6] Peter A. Petri, Michael G. Plummer and Fan Zhai, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment” Work Paper No. 119, October 24, 2011, p. 37

[7] “Economic survey of Canada 2008: Modernising Canada’s agricultural policies.” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. June 11, 2008. http://www.oecd.org/eco/economicsurveysandcountrysurveillance/economicsurveyofcanada2008modernisingcanadasagriculturalpolicies.htm

[8] “What is the Trans-Pacific Partnership?” CBC News, June 20, 2012. http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/story/2012/06/20/f-trans-pacific-partnership-explained.html

[9] Dawson, Laura. “Canada and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.” Speech, Wilson Center, Washington D.C., August 8, 2012.

[10] “The United States in the Trans-Pacific Partnership.” The Office of the United States Trade Representative. August 14, 2012. http://www.ustr.gov/about-us/press-office/fact-sheets/2011/november/united-states-trans-pacific-partnership

[11] Ward, John. “Making the Asia-Pacific Region a Top Priority for U.S. Trade.” International Trade Administration: Tradeology, December 7, 2011. http://blog.trade.gov/2011/12/07/making-the-asia-pacific-region-a-top-priority-for-u-s-trade/

[12] Levine, David S. “The Most Important Trade Agreement That We Know Nothing About.” Slate (July 30, 2012). http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2012/07/trans_pacific_partnership_agreement_tpp_could_radically_alter_intellectual_property_law.single.html

[13] Flynn, Sean. “Law Professors Call for Trans-Pacific Partnership Transparency.” InfoJustice, May 9, 2012. http://infojustice.org/archives/21137

[14] Congress of the United States House of Representatives, Open Letter to Ambassador Ron Kirk (Washington, DC: GPO, June 27, 2012). http://www.publicknowledge.org/files/TPP%20Letter%20FINAL.pdf

[15] Carter, Zach. “Obama TPP Trade Deal Secrecy Insulting, According to Senator Ron Wyden.” OpEdNews, June 7, 2012. http://www.tradereform.org/2012/06/obama-tpp-trade-deal-secrecy-insulting-according-to-senator-ron-wyden/

[16] Obama, Barack. Speech at the November Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, Yokohama, Japan, 2011.

[17] Available at Public Citizen. http://www.citizenstrade.org/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/tppinvestment.pdf

[18] National Democratic Convention Committee. “Renewing America’s Promise.” Paper presented at the 2008 Democratic National Convention, Denver, Colorado, August 13, 2008. http://www.citizenstrade.org/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/2008DemocraticPlatformbyCmte_08-13-08.pdf

[19] TPP Investment Chapter, Section A

[20] Chimni, B.S. “Third World Approaches to International Law: A Manifesto.” International Community Law Review 8 (2006), pp. 3-27.

[21] Earthjustice, Friends of the Earth, Institute for Policy Studies, Public Citizen, Sierra Club. “Key Elements of Damaging U.S. Trade Agreement Investment Rules that Must Not Be Replicated in TPP.” Public Citizen, February 2012. http://www.citizen.org/documents/tpp-investment-fixes.pdf

[22] Ibid.

[23] Intellectual Property Chapter available at http://keepthewebopen.com/tpp. A special thank you to Professor Sean Flynn, Professorial Lecturer and Associate Director for the Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property at the American University College of Law for his help on this subject.

[24] Flynn, Sean, Margot Kaminski, Brook Baker, and Jimmy Koo. “Public Interest Analysis of the US TPP Proposal for an IP Chapter.” Northeastern University School of Law Research Paper 82-2012 and American University WCL Research Paper 2012-07 (December 6, 2011).

[25] TPP Intellectual Property Chapter, Article 4.2; “Parallel Importation.” Australian Library and Information Association, March 1, 2010. http://www.alia.org.au/advocacy/copyright/your.ques.answered.html

[26] Agreement on Trade-‐Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Art. 6, Apr. 15, 1994, Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, Legal Instruments—Results of the Uruguay Round, 1869 U.N.T.S. 299 [hereinafter TRIPS].

[27] TRIPS Article 27.1

[28] TPP Intellectual Property Chapter, Article 8.1

[29] Doctors Without Borders Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines. “How the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement Threatens Access to Medicines.” TPP Issue Brief (September 2011). http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/press/2011/MSF-TPP-Issue-Brief.pdf

[30] “AIDS, Drug Prices, and Generic Drugs.” AVERT International AIDS charity. Updated August 2012. http://www.avert.org/generic.htm

[31] National Democratic Convention Committee. “Renewing America’s Promise.” Paper presented at the 2008 Democratic National Convention, Denver, Colorado, August 13, 2008. http://www.citizenstrade.org/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/2008DemocraticPlatformbyCmte_08-13-08.pdf

[32] TPP Intellectual Property Chapter, Article 12.4

[33] “The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (aka NAFTA on Steroids): What it could mean for the Environment.” Sierra Club. http://www.sierraclub.org/trade/downloads/TPP-Factsheet.pdf

[34] “Fracking.” Food and Water Watch. Last updated August 2012. http://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/water/fracking/

[35] “Analysis: Renco Group Uses Trade Pact Foreign Investor Provisions to Chill Peru’s Environment and Health Policy, Undermine Justice.” Public Citizen Global Trade Watch, March 2012. http://www.citizen.org/documents/renco-memo-03-12.pdf.

[36] World Trade Organization. United States — Measures Concerning the Importation, Marketing and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products: Dispute DS381 (June 13, 2012). http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds381_e.htm

[37] Office of the United States Trade Representative. Bipartisan Trade Deal (May 2007). http://www.ustr.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/factsheets/2007/asset_upload_file127_11319.pdf

[38] Free Trade Agreement between the United States of America and the Republic of Peru, U.S.-Peru, Art. 16.10.2(c), Apr. 12, 2006 [hereinafter U.S.-Peru FTA], available at http://www.ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade- agreements/peru-tpa/final-text

[39] “Asia and Latin American United Through the Trans-Pacific Partnership.” Inter-American Development Bank, January 31, 2012. http://www.iadb.org/en/topics/trade/asia-and-latin-america-united-through-the-trans-pacific-partnership.html

[40] Flynn, Sean. “Chilean Trade Officials Question TPP Benefits at Seminar in Santiago.” Info Justice, April 16, 2012. http://infojustice.org/archives/10712

[41] Park, Ariella and Rachel Spence. “Trans-Pacific Partnership: A Western Hemisphere View.” Council of the Americas, January 31, 2012. http://www.as-coa.org/articles/trans-pacific-partnership-western-hemisphere-view

[42] Ibid.

[43] Palmer, Doug. “Mexico to join Trans-Pacific Partnership talks.” Reuters, June 18, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/06/18/us-usa-mexico-transpacific-idUSBRE85H1LC20120618

[44] Sanchez, Luz Maria de la Mora. “Mexico and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.” Speech, Wilson Center, Washington D.C., August 8, 2012.

[45] Chang, Jack. “Asian investment boom seen in Latin America.” Salon, April 18, 2012. http://www.salon.com/2012/04/19/asian_investment_boom_seen_in_latin_america_2/

[46] Bernhardt, Jordan and Sabina Dewan. “Japan’s Inclusion Makes the Trans-Pacific Partnership a Big Opportunity.” Center for American Progress, May 8, 2012. http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2012/05/japan_tpp.html

[47] Udo, Chandler H. “Japanese Rice Protectionism: A Challenge for teh Development of Agricultural Trade Laws.” Boston College International and Comparative Law Review 31.1 (December 2008). pp. 169-184. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=iclr

[48] Yamashita, Kazuhito. “Ensuring Japan’s food security through free trade not tariffs.” East Asia Forum, March 10, 2010. http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2010/03/10/ensuring-japans-food-security-through-free-trade-not-tariffs/

[49] Smitka, Michael J. “Adjustment in the Japanese Automotive Industry: Microcosm of Japanese Cyclical and Structural Changes.” Washington and Lee University. http://home.wlu.edu/~smitkam/autoswithgraphs.pdf

[50] “South Korea prioritizes Asia trade pacts over Pacific partnership.” Reuters, May 17, 2012. http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/politics/AJ201205170023

[51] Stubbs, Richard. “ASEAN Plus Three: Emerging East Asian Regionalism?” Asian Survey 42.3 (2002). pp. 440-455. http://www.alternative-regionalisms.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/stubbs_aseanplusthree.pdf