The Potential of Cuba’s Search for Oil

The recent discovery of offshore oilfields in the Gulf of Mexico has given Havana new hopes of establishing rich deposits of its own, thereby decreasing Cuba’s present dependence on foreign energy sources.

Fidel Castro began to look for new energy suppliers immediately upon coming to power in 1959, and he soon found one. The Soviet Union was Cuba’s largest supplier of energy resources during the Cold War, but Moscow’s collapse in the early 1990s, coupled with the longstanding American embargo, drove the Cuban economy into a deep depression. Havana, in response, has begun implementing market-based reforms, including intensifying efforts to open the country to tourism,[1] as well as encourage strategic partnerships with other Latin American countries, most notably Venezuela.[2]

In 2011, Cuba produced about 55,000 onshore barrels of oil per day, mostly from the northern province of Matanzas, refining it at the island’s four refineries (in Cabaiguán, Cienfuegos, La Habana, and Santiago de Cuba). Consumer needs, however, call for over 170,000 barrels per day, making the island a net importer of oil.[3] Currently, the bulk of these imports come from Venezuela, which meets two-thirds of Cuba’s daily requirements thanks to an energy agreement the two countries signed in October 2000. Cuba has become a crucial partner for Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, as reflected in both countries’ membership in the rising Alianza Bolivariana para Amèrica Latina (ALBA) trade bloc.

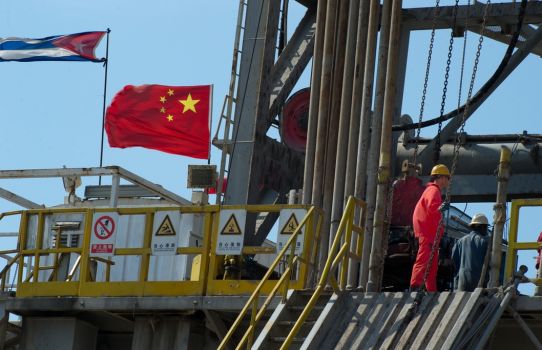

In early 2012, a deepwater drilling rig was built in China by an Italian company, Saipem, which is owned by the oil and gas multinational Eni, and then leased to Spain’s Repsol. The Spanish company began offshore oil exploration 22 miles north of Havana, in the Jaguey block of the Cuban Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), as early as 2004, and is hoping to find between 5 and 9 billion barrels in that area.[4] Yet Repsol will hardly be the only foreign company operating in Cuban territory, as it will be working in just six blocks within the EEZ, and will be doing so in cooperation with Norway’s Statoil-Hydro and India’s Ongc. 22 other blocks, meanwhile, have been awarded to other foreign companies, including Petronas (Malaysia), PetroVietnam (Vietnam), Gazprom (Russia), Sonagol (Angola), PDVSA (Venezuela), and CNOOC (China).[5] While each is eager to hit black gold in the region, it would take three to five years of drilling before real production could begin even if the deposits live up to expectations.[6]

The United States, which is not taking part in the drilling because of its embargo against Cuba, could nevertheless not be more interested. Washington, alarmed by the drilling site’s location just 60 miles from Florida’s coast, has been expressing its concerns about the potential environmental risks posed by the explorations, and has commissioned a panel of environmental and energy experts to discuss possible solutions to any potential disaster in the region. According to William K. Reilly, former head of the Environmental Protection Agency under George H.W. Bush, “the Cuban approach to this is responsible and appropriate to the risk they are undertaking.”[7] But should an accident similar to the BP disaster of 2010 occur, the absence of a bilateral oil spill agreement between the U.S. and Cuba, in conjunction with strict American regulations freezing the transfer of technology between the two countries, would threaten American interests in the region, as well as pose a real environmental danger to the entire Gulf of Mexico. The matter is further complicated by the fact that offshore explorations are not taking place in U.S. territorial waters, within Washington’s legal reach, and are therefore not governed by the Clean Water and Oil Pollution Acts. Thus, any U.S. effort to take control of the situation in the event of an oil spill would be much more difficult, and would be bound to cause a diplomatic incident. Clearly, Washington must begin to consider a possible adjustment or elimination of the restrictions imposed upon the Caribbean country, and ask itself whether the embargo truly still represents American interests.

Economically, it must not be forgotten that if the investigations of Repsol and others reveal that there is a considerable amount of oil in the Cuban EEZ, Cuba could be transformed from an oil-importing country to one of Latin America’s largest oil producers almost overnight. Such a stark transition would undoubtedly affect relations between Havana, Caracas, and Washington, as well as completely change the geopolitical equilibrium of the region, possibly producing explosive results.

Another crucial issue is the conflict between the Argentine and Spanish governments over Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s nationalization of YPF, a now-former Repsol subsidiary. On April 19th, the Castro administration announced its support for the takeover, stating that Argentina has the right to exercise permanent sovereignty over its natural resources. Such a controversial declaration, even if coherent once one takes into account Argentina’s alliance with Havana, could end up being a risky and counterproductive step for Cuba.

A potential geopolitical turning point for the region, the discovery of oilfields in the Cuban EEZ could represent Havana’s ticket to the further liberalization of Cuban institutions, an escape from poverty and underdevelopment, and the end of Washington’s disdain for their Caribbean neighbor. Still, the Cuban position on the Argentinian YPF seizure could prove problematic, and Havana would do well to reformulate its position in order to ease tensions with the Spanish oil company. At the same time, however, if the United States is interested in benefiting from this discovery and in staving off a potential ecological disaster mere miles from its southern coast, then it, too, must work to ease tension and adapt to the post-Cold War world.

To view sources, please click here.