Post-Coup Brazil: Temer’s Rise to Power and the New State of Exception

By Aline Piva, Research Fellow and Head of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs’ Brazil Unit, and Liliana Muscarella, Research Fellow at the Council On Hemispheric Affairs’ Brazil Unit

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Six coups, six different constitutions, and 13 presidents whose terms were cut short. Brazil has a long history of democratic ruptures and economic busts, but since democratically elected president Dilma Rousseff was illegally ousted on August 31, 2016, the country has witnessed the further deterioration of the rule of law and democratic legitimacy in all branches of government. The coup against Rousseff was not an isolated event: it was the result of a coordinated maneuver to overthrow the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT) government—a plan carried out by the Brazilian mainstream media and the country’s political and economic elites, with aid from the judiciary. Since Rousseff’s ouster, the de facto administration has drawn a tenuous hold on power from the steady deterioration of Brazilian institutions, creating a state of affairs with little resemblance to a democracy; and the very institutions that are supposed to guarantee constitutional rights are contributing to violence against opposition voices. This dynamic can be classified as an unconventional “state of exception” —one that has many similarities to the military dictatorship that began in 1964.

A “State of Exception” in Brazil?

Indicative of the crisis of legitimacy of constituted power in Brazil, some analysts are now arguing that the recent ruptures in Brazilian democracy are due to the so-called “state of exception” that became apparent with Rousseff’s illegal impeachment. A state of exception—initially conceived as akin to a “state of emergency” in which anything goes—is both triggered and engendered by the manipulation of democratic institutions and the instrumentalization of the law to legitimize illegal activities.[i] The impeachment and other manipulations by the current government are now “contaminating” other Brazilian institutions and further undermining the young democracy.[ii] The evolution of Rousseff’s ouster has brought into play the most reactionary elements of Brazil’s political spectrum and, given the right’s track record in Brazil’s dark past and recent government repression of dissent, this ominous trend poses an immediate threat to basic human and civil rights of the country’s disenfranchised constituents.

According to Allan Mohamad Illani, a scholar from the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (University of Rio de Janeiro State, UERJ), the term “state of exception” “defines a ‘state of law’ in which, on the one hand, the norm is in force,” but it is selectively applied to advance a political agenda. On the other hand, “acts that have no value of Law acquire their ‘strength’” through illegitimate means. The concept was first designed as a tool to protect the democratic state should it face an external threat. However, this analysis argues that the mechanism changed during the course of the 20th century from “an instrument of response to military threats” to “an instrument of containment of political and economic crises,” and toward a state of affairs in which it is impossible to dissociate the state of exception and the rule of law.[iii]

In a state of exception, the rules are established by casuistic interests, and only benefit a certain, few people.[iv] [v] In that sense, Rafael Valim, a professor from the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, PUC-SP), argues that “the exception undoubtedly undermines one of the pillars of the Democratic Rule of Law, that is, popular sovereignty.”[vi] In other words, democratic institutions that should guarantee the constitutional rights of the people—and that should recognize all citizens as equals—are subverted to guarantee the political and economic interests of a small, ruling elite.

One of the most striking features of a state of exception is that law enforcement can be manipulated in order to achieve certain political agendas. Indeed, Brazil has a long history of institutions within the government acting to protect specific interests disguised as being for the “greater good.” In 1964, the justification for the military coup was that the country needed to be protected from the “communist” threat and “cleansed” of the corruption of its political elites; the president at the time, João Goulart, had proposed a series of reforms for redistribution of wealth that had little to no resemblance to communism, but that threatened the privileges of Brazilian middle and upper classes. What followed was the implementation of a repressive regime that was completely aligned with U.S. interests and that stayed in power for 21 years. In 2016, the justification for what is now being recognized as a “soft coup” was that the country needed to be “cleansed” of the progressive Workers’ Party and that, having lost her political and popular support, Rousseff was unfit to finish her term.[vii] Just as in 1964, the alleged “corruption” of the Workers’ Party was only a facade behind which to put in power a government willing to implement a neoliberal agenda to bolster the interests of international capital.

Although democratic ruptures seem to be a familiar trend in Brazilian politics, Rousseff’s illegal impeachment was unique in that it was, among other things, the climax of a carefully planned attack to undermine the legitimacy of the Workers’ Party government and regain conservative power. According to Jessé de Souza, a Brazilian sociologist and writer:

the ouster of the president […] meant the culmination of an unprecedented siege in the country’s recent history: a judicial, political, and mediatic attack against the political and ideological hegemony initiated in the first government of [former] president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. The real purpose, however, was nothing new in relation to all other coups d’etat practiced in the nation’s past: to serve the financial and political interests of the small monetary elite. […] Brazil’s history has seen a series of coups d’état that have used corruption as a motto. The reason is simple: it lends itself effortlessly to be used arbitrarily as a selective weapon against the political enemy of occasion.[viii]

The present disintegration of Brazilian institutions for political gain is despicable in and of itself, but what is more worrisome are the human rights atrocities that accompany this state of exception—with little legal recourse—and that are reminiscent of the dictatorial “years of lead.” It is dangerous to view the extrajudicial killings, massive corruption, and general repression as simply another manifestation of the global right-wing discontent that seems to both alarm and despair much of the American populace. Instead, a disturbing era of Brazilian history is dangerously close to repeating itself and reverting to something similar to the military dictatorship that left 434 people disappeared and countless others tortured, including Rousseff herself.[ix] Recent developments, while perhaps less high-profile, are not all that different.

Rule of Law and Human Rights in a State of Exception

The illegal manipulations and democratic rupture that characterize a state of exception reverberate disturbingly in the current abuses being suffered by Brazilians. Since Temer’s takeover of the Brazilian state last year, atrocities ranging from extrajudicial police killings to political oppression to governmental corruption and the regression of social rights and constitutional guarantees have occurred—classic signals of a country in democratic crisis with no accountability. In the first two months of 2017, the number of deaths by police doubled to 182 in Rio de Janeiro, disproportionately decimating black favela populations.[x] Meanwhile, Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Landless Rural Workers’ Movement, MST), the largest social movement in Latin America, has also been targeted, as exemplified by the 61 deaths of such activists in 2016 and the recent murder of Waldomiro Costa Pereira, who was murdered by police forces in a hospital bed as he was recovering from a previous assassination attempt. These statistics and illicit activities are not random apparitions—they are haunts of previous dictators and troubled democracies that demand resolution in the new state of exception.

Corruption is recognized—or at least touted—as a problem by Brazilians on both side of the political spectrum. Therefore, an investigation into corruption in Brazil was a crucial development welcomed by many upon its inception in March 2014; after decades of unbridled bribery and money laundering, Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) finally promised an inquiry into the massive corruption that had too long benefited politicians and state economic interests while ignoring the country’s underprivileged. But the process itself is ridden with irregularities that seem to shield the very individuals suspected of the most illicit activities, while at the same time targeting specific individuals in order to promote certain partisan aims.

Despite the fact that the investigations are still underway, there is already cause for suspicion as to their integrity. First, there is the lack of convictions of people linked to certain parties, such as the conservative Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (Brazilian Social Democracy Party, PSDB). Just as worrisome are two other problems: first, the questionable soundness of the investigations; namely, the fact that the Workers’ Party and the left in general are allocated disproportionate attention in the investigations. This can be largely attributed to the way in which the media covers certain facts and not others, highlighting the allegations against leftist parties while virtually ignoring the corruptive manipulations committed by the PSDB. This is most evident in the simple division of airtime when reporting on the investigations. When Attorney General Rodrigo Janot first released the names of politicians potentially linked to the corruption scheme, TV Globo, for example, spent five minutes discussing Temer’s involvement, nearly 20 for Rousseff and 33 for former President Lula.[xi] Given Temer’s position of power relative to Rousseff’s and Lula’s, there is no reason for the disparity of airtime granted to these discussions. Secondly, and relatedly, those responsible for the operation seem to be instrumentalizing the persecution of Workers’ Party favorite Lula in order to prevent his eventual candidacy for reelection in 2018.[xii] [xiii] This has a pernicious long-term impact on the dynamics of Brazilian politics, and also contributes to the erosion of so-called “democratic institutions” in the country—especially the ones designed to combat corruption.

Going unaddressed due to this evasion of justice is the oppression of peaceful demonstrations and the targeting of social leaders and vulnerable communities in Brazil. The terms “political oppression” and “mass murder” have become nearly synonymous in Temer’s state of exception. Targeted populations include journalists, indigenous populations, and social movements like the MST. On one day alone, May 24, 10 MST campesinos were murdered in Pará state during a police raid.[xiv] Even everyday protesters are subjected to extreme oppression; most tellingly was the recent march of 200,000 in Brasilia against which Temer called the federal troops, who met the largely peaceful protesters with tear gas, flash bombs, and firearms—eerily reminiscent of a similar march, for similar causes, in 1996. In that year as now, there has been no legal recourse for such oppression, as the authorities that are supposed to investigate such cruelties are ineffectual.

Further shielding the government from accountability for these overt human rights violations is Temer’s newest Supreme Court Justice, Alexandre de Moraes. Following the highly suspicious death of Justice Teori Zavascki in a plane crash in January, Moraes was nominated by Temer to replace Zavascki—and thus, impeding the investigation of Operation Car Wash, in which Zavascki had been a major player. Moraes is a murky character in other senses, too; as Chief of Security of São Paulo, “he defended the use of lethal weapons by police forces in an operation to end the occupation of a school by teenage students.”[xv] He also has a questionable past with former Speaker of the Lower House Eduardo Cunha, having defended the Speaker’s corrupt activities before Operation Car Wash brought Cunha down (a development that was met with mixed reactions).[xvi]

Perhaps the biggest test of the right-wing’s cohesiveness was the May 30 leak of audiotapes in which Temer reveals an illicit accordance with Joesley Batista, a businessman currently under investigation in five different corruption inquiries. In the recording, Temer can be heard tacitly approving Batista’s continuing to give hush money to Cunha, a key figure in Rousseff’s overthrow.[xvii] What’s more, this hard evidence tipped the scales in Justice Fachin’s favor, prompting him to authorize the opening of investigations against the illegitimate president, as well as a third of his cabinet and the company that accepted one billion USD in bribes during the 2016 Olympics.[xviii] This is the second time in Brazil’s history that a president will be officially investigated while still in office.[xix] While a promising development, Temer’s ability to shield himself and his allies from corruption investigations goes even further: current Attorney General Rodrigo Janot, responsible for releasing the taped conversation and, in part, carrying out the investigations against Temer, announced that he will not run for a third term. Therefore, if Temer stays in power, he could potentially be the one responsible for choosing who will conduct these investigations against him.[xx]

A recent ruling on the legality of the Rousseff-Temer electoral platform when Temer was Rousseff’s running mate further emphasizes Temer’s seeming immunity.[xxi] The judicial action calling for the nullification of the 2014 platform on the grounds of alleged abuse of political and economic power in those elections was rejected with by four votes to three. The most striking feature of this decision is how Justice Gilmar Mendes—a long-term friend of Temer’s and the presiding judge of the case—changed his understanding of the facts. In March 2015, before Rousseff’s impeachment, the then-presiding justice, Maria Thereza de Assis Moura, ruled against the continuation of the trial, considering at the time that the allegations were too generic and lacked sufficient evidence. Mendes asked for the reopening of the case: for him, there was enough evidence, at that time, that their campaign had committed fraud. Strangely enough, now that Rousseff is no longer in power and Mendes’ friend and ally is, Mendes could no longer find strong evidence to convict their electoral platform. As professor Bruno Galindo points out, “the discrepancy in the Court’s understanding in such a short period of time may lead to a number of considerations: on the one hand, the volatility of the Court’s positions […]; on the other hand, the possibility that such a circumstance might favor casuistic rulings in the Court”.[xxii]

A final indicator of the current Brazilian state of exception and its historical foundations is the presence of U.S. support for right-wing governments, articulated via institutions like the Organization of American States (OAS). In 1964, as now, leftist governments in the hemisphere are politically and economically vilified by U.S. allies in the OAS and the more conservative ones are exalted as protectorates of human rights and democracy despite track records pointing to the contrary. Some examples of this in the present day may be found in recent manipulations taken in the OAS to denounce similar leftist governments (notably, Venezuela), while placing countries like Honduras and Mexico on a pedestal of U.S. allyship—moderating criticism of abuses perpetrated by state actors in those countries.

A Dubious Return to Democracy

What we see in Brazil today is the growing instrumentalization of the rule of law to achieve political ends and impose a neoliberal agenda consistently rejected in the ballot box. Frequently, flagrant violations of due process are dismissed as a “necessary evil” to achieve conservative goals. Just recently, a judge overruled an allegation contesting the way Operation Car Wash was being conducted, affirming that “extraordinary times” call for “extraordinary measures.” Coincidently, that is the same justification used by Colonel Brilhante Ulstra, Rousseff’s torturer, to justify the atrocities committed under the military dictatorship.[xxiii] As Brazilian judge Rubens Casara argues, “in a constitutional democracy [..] it is the responsibility of the judiciary to safeguard the legal limits imposed on political power, economic power and the exercise of its own jurisdictional power. The fact that political agents dismiss fundamental rights and guarantees […] reveals the dangerous path that is being followed” now in Brazil.[xxiv]

Those who argue that we are witnessing an end to the progressive cycle in Latin America, pointing to Brazil and Argentina to buttress their arguments, may have drawn their conclusions with too much haste. The pushback in Argentina and Brazil against the neoliberal regime, as well as the recent election of Lenin Moreno in Ecuador, are all indications that there is significant constituent resistance to a conservative wave. Furthermore, the ongoing attempts by OAS Secretary-General Luis Almagro, backed by the United States, to isolate Venezuela in order to legitimize a foreign intervention, while troublesome, is far from a done deal, as both regional and global actors continue to call for dialogue instead of war. Should Brazil be able to make a return to progressive, democratic rule, it would not only be a remarkable recovery for the country, it would also signify a concrete, regional shift in favor of Latin American integration and independence.

Whether such hopes are sustainable, though, is uncertain, as is Brazil’s own outlook. It is true that the climate of power is changing in the country: Brazilian media outlets that played a major role in the coup against Rousseff seem to have turned against Temer; protests against his illegitimate government are growing at a fast pace; and Temer’s political base is not as cohesive as it was a few months ago. However, while this may seem promising for the revival of the left, any change in this direction, including Temer’s removal, would need the approval of the same institutions that supported the coup against Rousseff and that are now compromised by the spill-off from the unconstitutional impeachment. So, whether it is a state of exception or merely a nation in crisis, Brazil’s outlook is undeniably grim. The only certainty is that the long-term consequences of the coup will haunt the Brazilian people for decades to come.

By Aline Piva, Research Fellow and Head of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs’ Brazil Unit, and Liliana Muscarella, Research Fellow at the Council On Hemispheric Affairs’ Brazil Unit

Additional editorial support provided by Larry Birns, Director at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

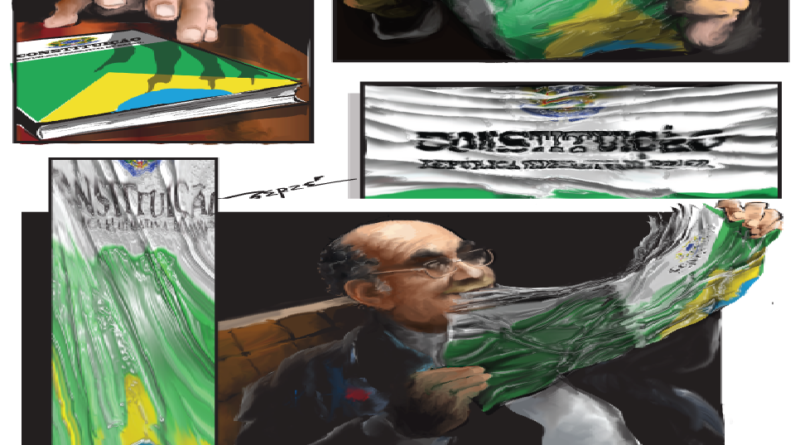

Featured image: Berzé: A Constituição; Taken from: Viamundo

[i] “A Brief History of the State of Exception.” A Brief History of the State of Exception by Giorgio Agamben. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/009254.html.

[ii]Matuoka, Ingrid. “A democracia tem sido corroída pelo Estado de Exceção”. CartaCapital. January 13, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://www.cartacapital.com.br/revista/933/dilma-a-democracia-tem-sido-corroida-pelo-estado-de-excecao.

[iii]Mohamad Hillani, Allan. “ENTRE A DEMOCRACIA E O ESTADO DE EXCEÇÃO: A AÇÃO POLÍTICA PARA ALÉM DO VOTO .” Direito UFPR. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.direito.ufpr.br/petdireito/pdfs/entre%20a%20democracia%20e%20o%20estado%20de%20excecao.pdf.

[iv] According to Merriam-Webster, the term “casuistry” means “a resolving of specific cases of conscience, duty, or conduct through interpretation of ethical principles or religious doctrine” — and implies the application of that interpretation to new, select instances.

[v] “Casuistry.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, n.d. Web. 20 June 2017.

[vi] Valim, Rafael. “Estado de exceção: a forma jurídica do neoliberalismo, por Rafael Valim.” Jornal GGN. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://jornalggn.com.br/noticia/estado-de-excecao-a-forma-juridica-do-neoliberalismo-por-rafael-valim.

[vii] Aline Piva – Frederick B. Mills. “What is a Coup? Analysing the Brazilian Impeachment Process.” Www.counterpunch.org. October 11, 2016. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/10/11/what-is-a-coup-analysing-the-brazilian-impeachment-process/.

[viii] “A radiografia do golpe.” O Cafezinho. August 24, 2016. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.ocafezinho.com/2016/08/24/a-radiografia-do-golpe/.

[ix] Romero, Simon. “Brazil Releases Report on Past Rights Abuses.” The New York Times. December 10, 2014. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/11/world/americas/torture-report-on-brazilian-dictatorship-is-released.html?_r=0.

[x] “Amnesty International.” Brazil: Spike in killings by Rio police as country faces UN review. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/05/brazil-spike-in-killings-by-rio-police-as-country-faces-un-review/.

[xi] Shalders, André. “Jornal Nacional Deu 4h Sobre Lista De Fachin; Lula Recebeu 33 Minutos.”Poder360.com.br. Poder360, 18 Apr. 2017. Web. 20 June 2017.

[xii] “Como a Lava Jato ‘interfere, interferiu e interferirá’ na política, segundo este professor.” Nexo Jornal. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://www.nexojornal.com.br/entrevista/2017/03/16/Como-a-Lava-Jato-%E2%80%98interfere-interferiu-e-interferir%C3%A1%E2%80%99-na-pol%C3%ADtica-segundo-este-professor?utm_campaign=selecao_da_semana_-_18032017&utm_medium=email&utm_source=RD%2BStation.

[xiii] As a leftist favorite in Brazil, attempts to delegitimize Lula and implicate him in Operation Car Wash and other corruption investigations — when there is no evidence — may be seen as an orchestration by the right to once again prevent the constituent power from expressing its wishes in the next election. Lula’s 2018 election would reveal the true will of the Brazilian people, not the elite that illegally and coercively brought Temer to power last year.

[xiv] “Brazil Police Killing of 10 Amazon Region Land Activists Under Probe.” U.S. News. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-05-25/brazil-police-killing-of-10-amazon-region-land-activists-under-probe.

[xv] Piva, Aline. “How the Zavascki Plane Crash Could Advance a Political Agenda in Brazil.” COHA. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://coha.org/how-the-zavascki-plane-crash-could-advance-a-political-agenda-in-brazil/and “Why Alexandre de Moraes is a bad name for the Brazilian Supreme Court.” Plus55. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://plus55.com/brazil-politics/2017/02/alexandre-moraes-brazilian-supreme-court.

[xvi] Piva, Aline. “Brazil Takes Another Step Towards Its Deconstruction Of Rule Of Law – Analysis.” Eurasia Review. March 07, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.eurasiareview.com/07032017-brazil-takes-another-step-towards-its-deconstruction-of-rule-of-law-analysis/.

[xvii] Mariana Schreiber -. “Delação da JBS: quais são os cenários possíveis caso se confirmem denúncias contra Temer – BBC Brasil.” BBC News. May 17, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-39957918 and “Joesley Batista e empresas foram alvos de 5 operações da PF desde 2016.” G1. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://g1.globo.com/economia/negocios/noticia/joesley-batista-e-empresas-foram-alvos-de-5-operacoes-da-pf-desde-2016.ghtml.

[xviii] “Brazil Judge Targets Dozens of Politicians for ‘corruption’.” BBC News. BBC, 12 Apr. 2017. Web. 16 June 2017.

[xix] Schreiber.

[xx] Bulla, Beatriz. “Oito candidatos concorrem ao cargo de Janot – Política.” Estadão. May 24, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,temer-vai-escolher-procurador-que-ira-investiga-lo,70001812181.

[xxi] “Por 4 votos a 3, TSE rejeita cassação da chapa Dilma-Temer na eleição de 2014.” G1. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/por-4-votos-a-3-tse-rejeita-cassacao-da-chapa-dilma-temer-na-eleicao-de-2014.ghtml.

[xxii] “O 7×1 de Carl Schmitt contra Hans Kelsen no Caso Dilma/Temer no TSE.” Justificando. June 14, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://justificando.cartacapital.com.br/2017/06/14/o-7×1-de-carl-schmitt-contra-hans-kelsen-no-caso-dilmatemer-no-tse/.

[xxiii] Vermelho, Portal. “Debate: Judici.” Portal Vermelho. Accessed June 15, 2017. http://www.vermelho.org.br/noticia/294593-6.

[xxiv] Casara, Rubens. “Tentação autoritária.” O Globo. Accessed June 15, 2017. https://oglobo.globo.com/opiniao/tentacao-autoritaria-21430663#ixzz4ixYA9AT3.