Odebrecht Pandora’s Box Opened: An Analysis of the Structure and Impact of Transnational Corruption in Latin America

By Sheldon Birkett and Tobias Fontecilla, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

Ángel Rondón, Odebrecht’s Dominican representative, was recently sentenced to one year in prison on corruption charges. Rondón is accused of having organized the distribution of $92 million in the form of bribes among several politicians to secure public work contracts and install a monopoly on the island.[i] The investigation further revealed the intricacy of the Brazilian conglomerate’s international bribing scheme. Odebrecht is a transnational company created in 1944 consisting of diversified businesses, which include infrastructure, energy, oil and gas, in addition to petrochemicals projects and services. On June 7, 2017, the Dominican Supreme Court judge Francisco Ortega sentenced several individuals to house arrest or prison on bribery charges whilst others were barred from leaving the country.

Odebrecht’s involvement in corruption first became global headline news in 2014 following the discoveries made by the Federal Police of Brazil, Curitiba Branch, as part of Operation Lava Jato (Car Wash).[ii] Operation Car Wash eventually implicated top Brazilian government officials including former president Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, current president Michel Temer (with audio tape evidence) and former Senate leader Delcídio do Amaral. Amaral was arrested after trying to buy the silence of jailed Petrobras executive Nestor Cervero who could implicate Amaral as a facilitator of illicit payments. Lula however has yet to be proven guilty, since no tangible evidence has been put forth. Cervero has denounced 74 individuals from across the political spectrum following a plea deal with the Brazilian government.[iii] Odebrecht was involved in numerous corruption scandals across Latin America between 2001 and 2016. In total, Odebrecht paid approximately $788 million in illegal bribes in twelve different countries securing public works contracts. Odebrecht’s corruption scheme has been associated with more than 100 projects across Latin America in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Venezuela.[iv][v] The scheme was able to operate almost undetected for 13 years until the commencement of Operation Car Wash. The United States, together with the Brazilian and Swiss governments, which have been major hubs for illicit money transfers, initiated legal action under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) on December 21, 2016. In a plea agreement the defendants agreed to pay $3.5 billion in penalties to all three countries.[vi] Given the magnitude of the corruption ring, the largest ever uncovered,[vii] strengthening preventive measures is of utmost importance when dealing with the propensity of grand corruption.[viii][ix] Court sentences in hindsight seem to do little to prevent corruption, especially when generous plea deals are proposed, limiting the risks involved when individuals and corporations decide to pursue these practices. Corruption itself and the exposure of corruption, was and continues to be, detrimental to developing economies in Latin America. Although concealed corruption gradually degrades the quality of investment spending, and ergo societies well being; the exposure of corruption results in the loss of investors confidence, and hence, a rapid reduction in investment.[x]

Money Laundering Circuit

In 2015, an anonymous source leaked over 11.5 million documents from the Mossack and Fonesca (M&F) legal firm’s database, now known as the ‘Panama Papers’ scandal. In them, more than 12 heads of states and over 140 politicians were proven to have used offshore tax havens. A grand total of 214,000 companies were established for 14,000 of M&F’s clients.[xi] The sheer number of documents may prove, as the investigation unfolds, that many more politicians, mobsters and other criminals may be involved. Odebrecht, unsurprisingly, was one of the largest clients of the firm, whose services included the design and implementation of a complex money laundering circuit. These large transfers of funds across national boundaries provided means of transferring funds discreetly for bribes and other devious purposes.

In order to pay for executives Paulo Roberto Costa, Pedro Barusco, and Renato Duque of the Petrobras semi-state-owned oil company,[xii] Odebrecht, with the help of M&F, transferred the bribes via a multilayered system of international money laundering in order to secure public contracts and receive preferential treatment. In this particular circuit, three layers have been uncovered. The first layer has its origins in the Swiss bank accounts of the Constructora Norberto Odebrecht S.A., alongside other company owned subsidiaries. With the use of offshore companies, established by M&F in the Virgin Islands and Uruguay,[xiii] Odebrecht was able to transfer the money.[xiv] This money would be ‘off the books,’ hidden through overpriced project budgets, fake purchases, and other techniques to inflate spending in order to funnel money into the bribing scheme.

The second layer has been described as the ‘linked accounts’ nexus. The first offshore companies would transfer money to other offshore companies internationally using bank accounts outside of Switzerland. These linked accounts were central to the circuit; the Meinl Bank, as well as other banks in Antigua and Panama, helped hide the funds true origin, free of scrutiny.

The final layer would transfer the money to shell companies in Panama, whose bank accounts were owned by Paulo Roberto Costa, Pedro Barusco, and Renato Duque.[xv] Shell companies are corporations without active business, which are often used as vehicles for concealing illegal activities.[xvi] Different accounts and shell companies disseminated across the globe, in addition to the hashing of the total sum of bribes into several smaller transfers, all helped scramble the path from briber to bribee. M&F has been identified as the main facilitator, however, its protagonism has also been proven in many other circuits. The following section will devise an in-depth analysis of the ‘linked accounts’ and of the middle man’s importance within the bribing system.

Concealing Odebrecht’s Financial Distribution

Odebrecht established the “Division of Structured Operations,” as a separate off-book communications system for the transfer of illicit payments. Referred as the “Department of Bribery,” by the U.S Department of Justice, the division organized illicit payments through the use of secured emails, instant messaging, codenames, and passwords. The division distributed the funds through offshore banks, cash payments, wire transfers, and suitcase deliveries. In exchange for the payments distributed by the “Division of Structured Operations,” Odebrecht and its subsidiary, Braskem, received preferential rates for buying raw material, government contracts, favorable legislation, and tax breaks. In addition to the political leverage gained, Odebrecht profited $3.336 billion and Braskem $465 million from bribes. Norberto Odebrecht, CEO Marcelo Odebrecht’s grandfather and founder of the conglomerate, remarked that bankrolling political campaigns was necessary to get the best contracts, “[Everything] that was happening was normal, institutionalized… in how all those political parties functioned.”[xvii]

Antigua is one of the most heavily implicated countries in facilitating the wiring of illicit funds through the “Division of Structured Operations.” In 2010, the Antigua & Barbuda Honorary Consul to Brazil, Luiz Franca, was complicit with helping Odebrecht in acquiring 51 percent of the Austrian Meinl Bank in Antigua. Additionally, according to a testimony from Franca, by 2010 Odebrecht operations sent more than $1 billion through the Antiguan Overseas Bank (AOB). Odebrecht’s involvement in Antigua was extensive: 33 banks fed Odebrecht bribe money to 71 different bank accounts.

By mid-2015, the transferring of funds through the Meinl Bank in Antigua was raising suspicions around Obedrecht’s financial activity. According to the United States District Court Eastern District of New York hearing in 2016, “Odebrecht Employee 4 attended a meeting in Miami, Florida, with a consular official from Antigua […] Odebrecht Employee 4 requested that the high-level official refrain from providing to international authorities various banking documents that would reveal illicit payments made by the Division of Structured Operations on behalf of ODEBRECHT.”[xviii] According to the District Court, the Antiguan official, Ambassador of Antigua to the United Arab Emirates, Casroy James, received a total payment of $4 million for his cooperation. The meeting in Miami was also intended to politically sway the Antiguan Prime Minister to reject Brazil’s request to conduct an official investigation into the Meinl Bank. In a press statement, James confirmed receiving money from Odebrecht and agreed to repay the funds acquired, stating that he did not go to Miami as an Antiguan official to meet with Odebrecht.[xix] Instead, James asserted that he traveled to Miami as an independent consultant for his own consultancy firm “Global Residency and Advisory Services Ltd.” contracted by the Meinl Bank.[xx] The veracity of James statement that he worked as an independent consultant in Miami is questionable, as no trace of “Global Residency and Advisory Services Ltd.” could be found on any search engines.

On March 30, 2017, U.S District Judge Paul Engelmayor ruled that shareholders of Braskem American Depository Receipts (ADRs) may pursue claims of defrauding Braskem investors from deceptively buying and selling naphtha[xxi] at below market price through Petrobras. This was a key mechanism in facilitating the Braskem corruption scheme.[xxii] ADRs are financial certificates, issued by a U.S. bank, that represent a specific number of shares on a foreign stock trade denominated in U.S dollars. ADRs are used as a means to decrease the cost of currency exchange and international regulatory differences on stock exchanges. Following the 2008 financial crash, the U.S. regulatory body, Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), amended section 12(g) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act. The amendment exempted paper application requirements for the regulation of ADRs, and only required foreign firms to provide non-U.S. financial disclosure documents.[xxiii] These changes in “over-the-counter” stock regulation aimed at liberalizing international stock exchanges; however, they have facilitated money laundering through the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The ease with which Braskem, and ergo Odebrecht, could launder money through the NYSE reveals the need for stronger regulatory measures from the SEC.

The Impact of Odebrecht’s Corrupt Business Ventures

A number of Odebrecht’s projects resulted in pernicious outcomes for the environment, for the displacement of peoples, and for local economies. Odebrecht’s use of bribery and other forms of political influence made it particularly difficult for critics of these harmful projects to be heard. In Peru for instance, Hitler Ananías Rojas Gonzales, an agricultural activist and mayor of the town of Yagen, situated in the northern part of the country, was assassinated in December 2015, after receiving several death threats. Gonzales was a fervent environmental activist who opposed the construction of a dam on the River Marañon awarded to Odebrecht, also known as the ‘Chadin ii project.’[xxiv] Gonzales argued that if the project were to be finalized, many farmers from the region would no longer be able to maintain their livelihood. Many would be forced to relocate, since 32 square kilometers of Amazonian forest would be flooded.[xxv]According to locals, Odebrecht had successfully infiltrated the local political elite, and with their help, tried to coerce the populace into signing an agreement to allow the project to continue. Government officials have both used physical force during protests and threatened to cut social programs, in order to satisfy Odebrecht’s agenda.[xxvi]

Similar human rights abuses have been noted in Brazil with the Belo Monte dam in the state of Pará. The funding for this dam was jointly made by the Andrade Gutierrez, Camargo Corrêa and Odebrecht firms.[xxvii] This monumental dam set to be the fourth largest in the world could, according to critics, displace 20,000 people.[xxviii] The dam was approved without the consent of indigenous communities in the region, which is in violation of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.[xxix] The resulting reservoir would cover 193 square miles of virgin Amazonian forest.[xxx] The impact on the biodiversity of the region and the Xingu river could translate into the loss of hundreds of species.[xxxi]

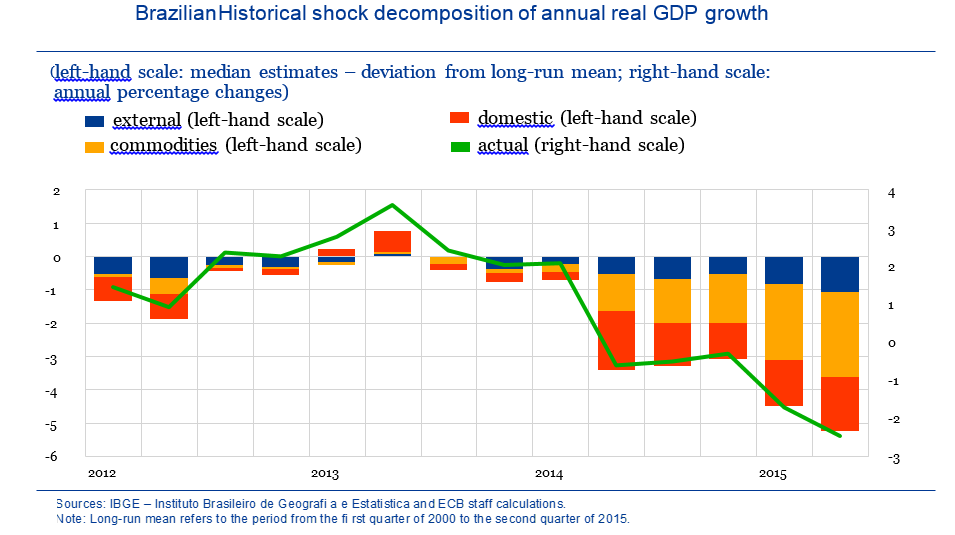

Nonetheless, the macroeconomic consequences have been much more alarming. The economic downturn Brazil experienced directly correlates with the public outbreak of Operation Car Wash. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), real GDP growth decreased sharply from 3.01 percent in 2013 to 0.5 percent in 2014. 2015 marked the start of a recession which averaged a negative 3.85 percent growth until the beginning of 2017. By the end of 2017, projections calculate Brazilian growth will reach 0.68 percent, showing first signs of a possible recovery.[xxxii] The Brazilian Ministry of Finance has argued that the decline of Petrobras’ investments, due to the large-scale scandal in the domestic economy, has subtracted around 2 percentage points from the GDP growth in 2015 alone.[xxxiii] Although corruption is not the sole factor in the decline of the Brazilian economy, it has sharply contributed to the recession alongside the fall of global commodity prices in the recent years.[xxxiv] The rest of the region might feel the ripple effect from the downturn in Brazil, and decrease in foreign investment, due to the loss of trust in Latin American politicians. Peruvian president Pedro Pablo Kuczynsk, who is also suspected of corruption, has promised a gradual disentanglement from Odebrecht in Peru. In March, he stated that in light of recent developments, many of the projects undertaken by the conglomerate will be terminated within the next six months.[xxxv] Other countries may take similar measures, which based on their level of commitment with the Brazilian company may translate into the loss of investments and distort GDP growth projections. As a result, declines in growth may manifest themselves in the region.

Provisions to Combat Grand Corruption

Odebrecht’s involvement in bribing government officials for preferential treatment of public works contracts, facilitated by an intricate web of international money laundering, was truly pervasive throughout Latin America. Merely criticizing the actions of Odebrecht is simply not enough; it is essential that governments take a proactive stance when combating grand corruption. The following five provisions could help in this pressing endeavor.

Firstly, the adoption and enforcement of Freedom of Information (FOI) laws, as a means of increasing government transparency is a preventative measure towards reducing corruption activities. Freedom of Information laws give citizens the right to access government information at the national level. Adequate FOI laws can increase democratic participation, protect the rights of citizens, increase functionality of governing bodies, and improve access to past legal disputes.[xxxvi] By increasing politicians’ risk of exposure, transparent FOI laws reduce the expected utility of corruption.[xxxvii]

Secondly, it is necessary to develop sound democratic institutions as a preventative measure against grand corruption. A quantitative study, Natural Resource, Democracy and Corruption, measured 124 countries between 1980-2004, and found that “natural resource rents increase corruption if and only if the quality of the democratic institution is below a certain threshold level.”[xxxviii] The findings present that sound democratic institutions are central to fighting corruption, irrelevant of regulating rent seeking activities.

Thirdly, although plea deals reduce time-consuming investigative work, such leniencies drastically decrease the risks associated with individuals choosing to partake in corruption. In other words, the benefits undertaken when engaging in these illicit activities greatly outweigh the costs (i.e prison time); thus, there are no real incentives for corruption to cease. The ‘big fish’ tactic recommends punishing high-profile corrupt individuals as harshly as possible, demonstrating a real desire to apply anti-corruption reforms to the public and deter possible future instances of corruption.[xxxix] Others have proposed to adjust punishment in proportion to the bribes received by public officials, as well as proportional to the profits obtained by the briber as a result of his illicit payments.[xl]

Fourthly, past international agreements have proven inefficient in countering grand corruption. The Organization of American States has drafted an Inter-American Convention Against Corruption signed by 33 parties. It has stated two objectives: promoting mechanisms to combat corruption across member states and enhance cooperation to detect, prevent, and punish instances of corruption.[xli] Many other international institutions offer similar promises and cooperative measures, such as the International Monetary Fund, Interpol, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, to name a few. Nonetheless, relying exclusively on the current information-sharing and evaluation services that these institutions provide, is insufficient to prevent grand corruption. The need to manufacture an effective ‘carrot and stick’ approach has yet to be formulated. Governments who would allow international institutions to investigate freely within their jurisdictions, and willingly agree to implement anti-corruption reforms would be rewarded with preferential tariffs, financial aid, and other benefits. If they refuse, they would be excluded from these economic and diplomatic benefits.[xlii]

Finally, pervasiveness of international capital flows has incentivized offshore preferential tax regimes, known as tax havens. Although tax havens increase international investment in poorer countries, this has made such countries more susceptible to money laundering. Therefore, money laundering prevention should be addressed through stronger regulatory measures of offshore financial centers.[xliii] Regulation from within financial sectors is sometimes weakened in order to maintain competitiveness with other tax havens.[xliv]It is necessary for tax haven regulation to be implemented from the “outside-in,” creating an internationally-level playing field. The OECD report Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue, concluded that “[Member countries] need to act collectively and individually to curb harmful tax competition and to counter the spread of harmful preferential tax regimes.”[xlv] Collective regulatory agreements, like the OECD project, could counteract negative preferential tax regimes which can result in money laundering and other illicit financial activities.

Right wing parties in Brazil, alongside other countries, have used Operation Car Wash as a defamation strategy to gain momentum. However, this has backfired as individuals within their ranks have been associated with the scandal. This might translate in an increase in vote shares for fringe political parties on the right and left. Future incumbent governments regardless of ideological inclination, should address the elimination of systemic grand corruption in order to restore legitimacy. This is not the time for articulate political rhetoric, rather, detailed policy formulation should be proposed to the constituency to ensure a sound economic development in the region, free from corruption.

By Sheldon Birkett and Tobias Fontecilla, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Dr Charles H. Blake, Senior Research Fellow, Mitch Rogers, Extramural Contributor, and Alex Rawley, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Featured Image: Odebrecht Taken From: Flickr

[i] “Quién es Ángel Rondón Rijo, el empresario citado por la Procuraduría en el caso Odebrecht,” Www.diariolibre.com, January 10, 2017, https://www.diariolibre.com/noticias/quien-es-angel-rondon-rijo-el-empresario-citado-por-la-procuraduria-en-el-caso-odebrecht-FM5961106.

[ii] Will Connors, “How Brazil’s ‘Nine Horsemen’ Cracked a Bribery Scandal,” The Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-brazils-nine-horsemen-cracked-petrobras-bribery-scandal-1428334221.

[iii]Daniel Gallas, “Brazil’s Delcidio do Amaral: Turncoat or whistleblower?” BBC News, May 5, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-36211526.

[iv]“United States of America Against Odebrecht S.A.,” United States District Court Eastern District New York, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/919911/download.

[v] Two Portuguese-speaking African nations, Angola and Mozambique, were also involved.

[vi] “Odebrecht and Braskem Plead Guilty and Agree to Pay at Least $3.5 Billion in Global Penalties to Resolve Largest Foreign Bribery Case in History,” The United States Department of Justice, December 21, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/odebrecht-and-braskem-plead-guilty-and-agree-pay-least-35-billion-global-penalties-resolve.

[vii]“Odebrecht: The company that created the world’s biggest bribery ring,” CNNMoney, http://money.cnn.com/2017/04/05/news/economy/odebrecht-latin-america-corruption/index.html.

[viii] “Corruption is behaviour which deviates from the formal duties of a public role because of private-regarding (personal, close family, private clique) pecuniary or status gains; or violates rules against the exercise of certain types of private-regarding influence.” This includes behaviours such as bribery, nepotism, and misappropriation. Grand corruption refers to: “high-level officials pocketing money from kickbacks, theft, embezzlement, insider deals, and the like. Privatizations of public enterprises provide some of the most spectacular recent cases of grand corruption in the region.”.

[ix] BLAKE, CHARLES H., and STEPHEN D. MORRIS, eds. Corruption and Democracy in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009.

[x] Méon, Pierre-Guillaume, and Khalid, Sekkat. “Does Corruption Grease or Sand the Wheels of Growth?” Public Choice 122, no. 1/2 (2005): pg. 69-97.

[xi] Juliette Garside, Holly Watt, and David Pegg, “The Panama Papers: how the world’s rich and famous hide their money offshore,” The Guardian, April 3, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/apr/03/the-panama-papers-how-the-worlds-rich-and-famous-hide-their-money-offshore.

[xii] Petrobras happens to be the largest company in Brazil. Jonathan Watts, “Brazil’s largest company, Petrobras, accused of political kickbacks,” The Guardian, September 17, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/17/brazil-petrobras-scandal-oil-general-election.

[xiii] Such as Smith & Nash Engineering Company INC, Golac Projects, and Arcadex Corp.

[xiv] Romina Mella and Gustavo Gorriti, “How Brazil’s Odebrecht Laundered Bribe Money,” InSight Crime | Organized Crime In The Americas, March 30, 2016, http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/how-brazil-odebrecht-laundered-bribe-money.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] “Shell Corporation,” Investopedia, November 26, 2003, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/shellcorporation.asp.

[xvii]Michael Smith, Sabrina Valle, and Blake Schmidt, “No One Has Ever Made a Corruption Machine Like This One,” Bloomberg.com, June 8, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-06-08/no-one-has-ever-made-a-corruption-machine-like-this-one.

[xviii]“United States of America Against Odebrecht S.A.,” United States District Court Eastern District New York, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/919911/download.

[xix]Casroy James, “Press Statement By Ambassador E. Casroy James On The Matters of Odebrecht SA, Meinl (Antigua) Ltd and Antiguan Officials,” Antigua Observer, December 28, 2016, http://antiguaobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Press-Statement-by-Ambassador-Casroy-James-on-the-matter-of-Odebretch-SA.pdf?x35888.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Substances such as coal, shale, or petroleum.

[xxii]Jonathan Stempel, “Brazil’s Braskem must face U.S. lawsuit over Petrobras scandal,” Reuters, March 31, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/braskem-lawsuit-idUSL2N1H80PV.

[xxiii]Securities and Exchange Commission, “Exemption from Registration Under Section 12(g) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For Foreign Private Issuers,” United States Securities and Exchange Commission, September 5, 2008, https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2008/34-58465.pdf.

[xxiv] “Proyecto Hidroeléctrico Chadín II,” BNamericas, https://www.bnamericas.com/project-profile/es/chadin-ii-hydro-project-chadin-ii.

[xxv]“Environmental Rights Leader Assasinated in Peru,” News | teleSUR English, http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Environmental-Rights-Leader-Assasinated-in-Peru-20151229-0030.html.

[xxvi] Comunicación, Tejido De, “Perú: Comunidades se pronuncian sobre Central Hidroeléctrica Chadín II en el río Marañón,” http://anterior.nasaacin.org/index.php/informativo-nasaacin/viviencias-globales/6284-per%C3%BA-comunidades-se-pronuncian-sobre-central-hidroel%C3%A9ctrica-chad%C3%ADn-ii-en-el-r%C3%ADo-mara%C3%B1%C3%B3n.

[xxvii] Jonathan Watts, “Brazil: insider claims Rousseff coalition took funds from Belo Monte mega-dam,” The Guardian, April 8, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/08/brazil-rousseff-corruption-belo-monte-dam.

[xxviii]“The Belo Monte Dam,” The Belo Monte Dam | AIDA, http://www.aida-americas.org/our-work/human-rights/belo-monte-dam.

[xxix]Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Sonia Barbosa Magalhaes, “Experts Panel Assesses Belo Monte Dam Viability,” October, 2009,http://assets.survivalinternational.org/documents/266/Experts_Panel_BeloMonte_summary_oct2009.pdf.

[xxxii]“Domestic product – Real GDP forecast – OECD Data,” The OECD, https://data.oecd.org/gdp/real-gdp-forecast.htm.

[xxxiii] “What is driving Brazil’s economic downturn?” European Central Bank, 2016, http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/eb201601_focus01.en.pdf?64a2cdbd9c4a9c254445668338164746.

[xxxiv] Henry Sanderson, “Explainer: Why commodities have crashed,” Financial Times, August 24, 2015, https://www.ft.com/content/459ef70a-4a43-11e5-b558-8a9722977189.

[xxxv] “Odebrecht could abandon all projects in Peru within six months: Kuczynski,” Reuters, March 05, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-peru-corruption-odebrecht-idUSKBN16C0VX.

[xxxvi] David Banisar, “Freedom of Information Around the World,” Privacy International, 2006, pg. 8, http://www.freedominfo.org/documents/global_survey2006.pdf.

[xxxvii]Daniel Berliner, “The Political Origins of Transparency,” The Journal of Politics 76(2), pg. 479-491, http://www.danielberliner.com/uploads/2/1/9/0/21908308/berliner_jop_2014_-_the_political_origins_of_transparency.pdf.

[xxxviii] Sambit Bhattacharyya, Roland Hodler, “Natural Resource, democracy and corruption,” European Economics Review, August 12, 2008.

[xxxix]Robert Klitgaard, “Controlling Corruption,” University of California Press, 1988, pg. 186.

[xl] Susan Rose-Ackerman, Corruption: A study in Political Economy, New York: Academic Press.

[xli] “Organization of American States: Democracy for peace, security, and development,” OAS, August 1, 2009, http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/inter_american_treaties_B-58_against_Corruption.asp.

[xlii]Susan Rose-Ackerman, “International Actors and the Promises and Pitfalls of Anti-Corruption Reform,” (2013). Faculty Scholarship Series. Paper Number 4944. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5954&context=fss_papers.

[xliii] Peter Schwarz, “Money launderers and tax havens: Two sides of the same coin?” International Review of Law and Economics, January 21, 2010, pg. 46.

[xliv] Ibid, 39.

[xlv] “Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue,” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, April 9, 1998, pg. 56, http://www.uniset.ca/microstates/oecd_44430243.pdf.