Neo-Paramilitary Gangs Ratchet Up Their Threat to Colombian Civil Society and the Long Term Survival of Civic Rectitude in the Public Arena

- The emergence of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) represented the largest and most violent paramilitary group in the country, funding its murderous activities by means of the immensely enlarging ongoing drug trade.

- The Colombian government enacted Decree 128 and the Justice and Peace Law to launch and subsequently monitor the demobilization process, which failed under the Uribe administration, and led to the emergence of neo-paramilitary drug gangs known as the Bacrims. (Las Bandas Criminales)

- The Bacrims are still carrying out their atrocities with a modus operandi similar to that of their AUC paramilitary predecessors. This has resulted in human rights violations and stepped-up drug trafficking.

- The Bacrims continue to maintain a strong presence in municipalities where Uribe-backed candidates claimed victory in the October 30, 2011 elections, and their long-term success would unquestionably threaten the prospects for peace in Colombia.

Executive Summary

Colombia’s first paramilitaries were known as ‘self-defense groups’, after they began to emerge in the 1960’s. Most of their funding came sub-rosa from the Colombian military, and they committed continuous acts of sharpening violence against rural civilian bands perceived as supporters or sympathizers of the guerrillas. In 1997, a new paramilitary group commonly known as the United Self- Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) stepped into the spotlight. From that point on, human rights abuses dramatically increased until reversed by the demobilization process, which began in 2003. Overall, the demobilizing process proved to be ineffective, despite the Colombian government’s efforts to eradicate both leftist and rightist armed groups. The former paramilitary groups have evolved into criminal bands known as the Bacrims. Today, the groups are heavily involved in operations ominously similar to those of their AUC predecessors, and also distinctly influenced the recent October 30, 2011 elections. Although the majority of the candidates supported by President Santos won the recent local elections, the Bacrims continue to maintain a lingering presence particularly in municipalities where Uribe-backed candidates were not able to hold on to their elected positions. The unsettling influence of this neo-paramilitary group will continue to challenge the prospects for peace in Colombia.

The history of paramilitary groups is rife with acts of violence and forced displacement, sizeable numbers of civilian casualties, and a strong military presence dispersed throughout the country. The evolution of former paramilitary forces into neo-paramilitary Bacrims is due to the woefully ineffective demobilization process and the government’s inability to monitor its success. Violence directly attributable to neo-paramilitary groups has dramatically increased in Colombia. The Colombian government must be more proactive in combating the Bacrims, beginning with an investigation into the alleged or historical ties between the neo-paramilitary drug gangs and the winners of recent, national, and regional elections.

Historical Emergence of Paramilitaries

Both the guerrillas and the paramilitaries originally evolved from the protracted and brutal political conflict in Colombia between the late 1940s and early 1950s, known as La Violencia, waged between the Liberals and Conservatives. Therefore, in 1965, right-wing Colombian security forces initiated new military tactics aimed at diminishing the pervasive military capacity of powerful leftist guerrilla forces, mainly based in rural parts of the country. Decree 3398, which became permanent with the introduction of Law 48 in 1968, allowed the military to “create groups of armed civilians to carry out joint counter-insurgency operations.”[1] In the years following, Law 48 would lead to the creation of thousands of ‘self-defense’ paramilitary groups, which would later become responsible for the displacement of 3.6 million people[2], along with “tens of thousands of other civilian[s] … victims of torture, kidnapping, and disappear[ances].”[3] Labor unionists, small landowners, and rural farmers were often targeted because they were viewed by the paramilitaries as guerrilla sympathizers. “Paramilitaries were also used by local politicians to eliminate political opponents and to control social protest by targeting activist and peasant leaders.”[4] This interconnectedness between paramilitaries, economic elites, political leaders, and the military contributed to numerous acts of notorious human rights abuses.

The AUC Rises to Power

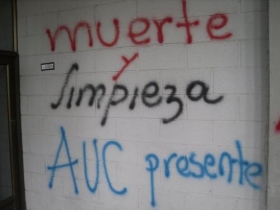

Despite major human rights atrocities committed by these “self-defense groups,” an even larger and more violent paramilitary group known as the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) emerged into the spotlight. Two brothers, Carlos and Vicente Castaño, founded this murderous body in 1997. The AUC proved to be extremely effective in its unqualified brutal methods, mobilizing several smaller independent paramilitary groups under one command, while actively promoting their overall goal, including the elimination of FARC leftist guerrillas and their supporters. The AUC’s tactical decision to combine multiple paramilitary groups and pool resources greatly increased their influence in the region and consolidated territorial control. In addition, the accumulated power and influence of the AUC was greatly augmented by the abundance of funding the faction received from the thriving drug trade in the late 1990s. Carlos Castaño claimed that “seventy percent of AUC revenue came from such trafficking.”[5] With funding from the drug trade and the military, the AUC prospered as a paramilitary organization, carrying out massive human rights atrocities, including random killings carried out until the early 2000s.

Directly after his inauguration in August 2002, right-leaning President Álvaro Uribe began talks with the paramilitaries to move towards demobilization. Although “the AUC viewed Uribe as a president they could do business with, they then declared a permanent ceasefire on December 1, 2002…”, largely because their brutal methods were embarrassing to Bogotá. [6] This ceasefire provided a sense of relief not only for Uribe, but also for the many other victims of paramilitary violence. However, Juan Forero in the New York Times article argued that paramilitaries’ motivations for demobilizing were merely to fulfill their own “desire to obtain a deal that [would]… allow them to avoid extradition to the U.S while serving as little time in prison for their crimes as possible.”[7] It became apparent that tAAAhe ultimate fate of both the paramilitary groups and of their helpless victims were not destined to be determined within the Colombian justice system.

Decree 128

The majority of paramilitaries demobilized because of Decree 128, which was enacted on January 22, 2003. The most important section of this decree, Article 13, stipulated certain legal and economic benefits to be derived by members of these armed groups who were not under investigation for crimes involving “atrocious acts of ferocity or barbarism, terrorism, kidnapping, genocide, and murder committed outside combat.”[8] Although most of the paramilitary groups routinely had committed such types of violations, if there was no pending investigation into such matter, then they would not be prosecuted under Decree 128. Most of the armed groups that benefited from this decree were under investigation for “illegal carrying of arms and membership of an illegal armed group,” rather than for the more “atrocious acts” listed.[9] Those not penalized under the decree were to then be tried under Justice and Peace Law.

The Justice and Peace Law and the “Sham” Hearings

The Justice and Peace Law, approved by Congress on June 21, 2005, required that paramilitaries who did not fall under Decree 128 be “tried at so-called ‘free version’ hearings and sentenced to no more than eight years imprisonment, which they could serve on ‘work farms.’”[10] According to an International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) report published in 2007, only eight percent of the more than 30,000 demobilized paramilitaries were effectively prosecuted under the Justice and Peace Law. Therefore, this ruling was largely ineffective, as it disregarded the fundamental principle of ensuring that combatants were “effectively removed from the conflict and not simply ‘recycled’ or ‘redefined’ into new armed, yet legal, structures.”[11] The actions covered by the Justice and Peace Law should have justified harsher prison sentences, including specific requirements and provisions regarding reintegration into society. Many human rights organizations have viewed this law as a sham, suggesting that it was designed mainly to help war criminals assimilate back into the community.[12] Moreover, at the “free version” sessions, “paramilitaries were not forced to confess their crimes, disclose the names of those who supported their structures, or even show repentance for their crimes.”[13] These “free version” hearings also provided little safety for the victims who had attended them. Since these hearings began, “sixteen victims have been murdered with absolute impunity.”[14] Not only has the Justice and Peace Law proved to be something of a pretense, but the Colombian government has also continued to be extremely ineffective in monitoring the demobilization process of paramilitary units.

Paramilitary Demobilization: A Failed Process

In September 2007, when President Álvaro Uribe told his United Nations audience that in Colombia, “…there is no paramilitarism. There are guerrillas and drug traffickers”[15] he conveyed the success of the Colombian government after 31,671 paramilitary forces laid down their arms in the demobilization process. However, the government failed to verify the identities of these demobilized forces, particularly as many Colombians disguised themselves as stand-ins for guilty paramilitary perpetrators who continued to carry out their illegal operations. According to Human Rights Watch, seventy-five percent of those who demobilized in Medellín were not true paramilitary soldiers. In addition, the government failed to oversee the process in which the AUC forces were demobilized since they tracked the locations of no more than five thousand former paramilitary members.

Throughout the procedure, the government also failed to target former paramilitary networks and the assets that sustained the groups, leading up to the emergence of the neo-paramilitary Bacrims. In turn, this group made use of former paramilitary drug routes, investment networks, and support services within a number of military and political sectors; the AUC evidently infiltrated the political system, putting eighty members of the Colombian Congress under investigation for their links to former paramilitary groups.[16] Many Colombian security forces regrettably are known to continue to collaborate, tolerate, and support these neo-paramilitary Bacrims and their illegal activities.[17]

The Bacrims: Neo-Paramilitary Drug Gangs

The Bacrims, heirs to the multi-million dollar drug trafficking operations formerly run by the AUC, operate in 152 municipalities throughout seventeen departments in Colombia.[18] As they gradually evolved, these neo-paramilitary drug gangs have inherited the strategic locations their paramilitary predecessors once used. This has provided the Bacrims with access to drug crops, trafficking corridors, and departure points for ships. According to General Óscar Naranjo, Colombia’s National Police commander, the “biggest threat to national security is now the activities of the Bacrims.” [19] As a result of their activities, violence has greatly increased in Colombia and the Bacrims are responsible for as much as the twenty-five percent increase in the number of kidnappings and massacre victims since their inception.[20] Police authorities have reported that 7,200 out of 15,400 homicides that occurred in Colombia last year were related to fighting between rival Bacrim street gangs.[21]

The Bacrims also, according to government officials, have collaborated with several guerrilla groups such as the FARC and the National Liberation Army (ELN) to promote their common interests in the drug trade. According to General Alberto Mejia, commander of Colombia’s fourth army brigade, the FARC and the Bacrims continue to assist each other as “the Bacrim pay in supplies, ammunition, and weapons,” while the rebels “protect Bacrim leaders and even train some of their men.”[22] This collaboration of far left and right-wing groups undoubtedly has prolonged Colombia’s civil conflict. This clearly distinguishes the Bacrims from the AUC, who never wavered from their core objective of defeating the guerrilla rebels.

These new successor groups are also deeply involved in kidnappings, murders, smuggling, extortion, money laundering, and anti-union violence, which also has lead to the enormous internal displacement of civilians. According to the widely respected Colombian NGO Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES), the number of displaced persons in Colombia rose from 305,961 persons in 2007 to 380,683 persons in 2008.[23] Despite the increasing number of human rights violations affecting Colombian citizens, the government has failed to combat problems of displacement and anti-union violence. Along with forced displacements caused by the Bacrims, there had also been an elevated level of violence leading up to the recent October 30, 2011 elections.

Future Prospects for Colombia

The Bacrims successfully have perpetrated acts of violence leading up to the recent local, municipal, and gubernatorial elections on October 30, 2011. As of September 22, 2011, 138 acts of violence, including threats, attacks and kidnappings, have been carried out against candidates for local office. [24] In addition, according to a report by Insight Crime, like their AUC forerunners, the Bacrims effectively utilized fear to manipulate the October 30, 2011 elections by infiltrating the political system, bribing likely elected candidates, as well as murdering 41 political opponents. These consistent cases of violence surrounding political candidates should be an incentive to President Santos and the victorious local candidates to acknowledge the growing presence of the Bacrims and their strong will to exist, even triumph. Moreover, the Bacrims should be watched with the greatest of care, so that newly elected officials maintain their vigil and are not caught off guard.

According to Noticias Uno, a Colombian newscast, ninety percent of the candidates supported by Uribe lost in their Sunday races, including Enrique Peñalosa, who was decisively defeated by his long-term political enemy and former guerilla fighter, Gustavo Petro, in the race for the mayoralty of Bogotá. [25] However, pockets of support for Uribe remained in areas ridden with neo-paramilitary violence, such as Córdoba, where Uribe-backed candidates suspiciously were able to retain ninety percent of the municipalities.[26] The Colombian government and newly elected officials should closely monitor these areas where Uribe still retains an intimidating degree of influence due to historical ties with former paramilitaries. Moreover, at a recent Washington, D.C. panel regarding the ongoing influence of the Bacrims, a Colombian expert asserted that “a strategic advantage for neo-paramilitary groups is to get political officials on their side.”[27] Therefore, it will be crucial to closely monitor future developments within the newly modified political arena.

As recently as October 31, 2011, President Santos formally announced the dissolution of the Administration Department of Security (DAS), the extremely corrupt and violence-prone Colombian intelligence agency, which has a long “history of collaboration with the AUC — that includes helping the paramilitary group to traffic drugs and launder the proceeds, as well as sharing intelligence.”[28] This new political achievement by President Santos should be praised by his supporters, and should be accepted as a step forward in targeting corruption and diminishing the large influence of the Bacrims. “About half the 6,000 DAS employees will transfer to the chief prosecutor’s office…others are being shifted to the national police and related government ministries.”[29] Effectively neutralizing these DAS staff members should be one of the main tasks of the Santos administration. The Colombian government should actively prevent employees from establishing ties to neo-paramilitaries as they proceed to be integrated into other national police and governmental units. With the dissolution of the DAS, the Colombian government will hopefully be more proactive in combating the corruption that currently exists throughout the bureaucracy, thwarting the political influence of the Bacrims, and improving the modest prospects for peace in today’s Colombia.