Leaving Behind the “Axis of Unity”: The Future of Iranian-Latin American Relations

On June 14, the Iranian people elected Hassan Rouhani as the nation’s new president in an election that was hailed by the international community as a potential turning point in Tehran’s foreign policy, as Rouhani is widely seen as a moderate. After the White House congratulated Rouhani on his victory, Secretary of State John Kerry briefly expressed his hope for the future of Iran: “[President] Rouhani pledged repeatedly during his campaign to restore and expand freedoms for all Iranians. In the months ahead, he has the opportunity to keep his promises to the Iranian people.” Such a statement shows that the White House is demonstrating cautious optimism when it comes to improving relations between Washington and Tehran, especially after Rouhani’s recent comments reaffirming his desire for a “dialogue” with world powers.

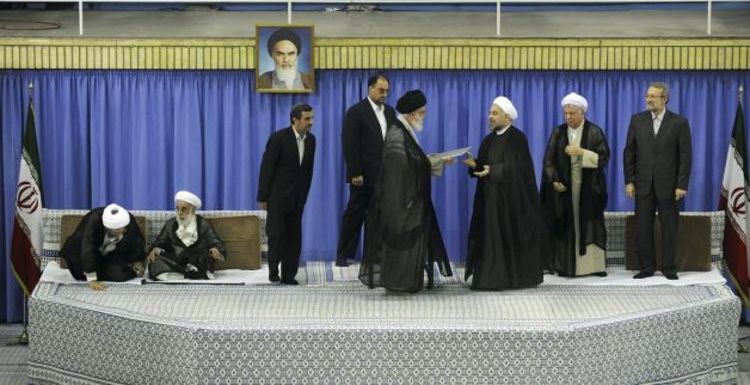

Rouhani assumed office on Saturday, August 3, replacing the at times relatively unpopular and often contentious outgoing president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Under Ahmadinejad, the Islamic Republic strengthened its ties to Latin America, particularly to the leftist, anti-U.S. bloc led by Venezuela and its late president, Hugo Chávez. However, Ahmadinejad’s tenure also brought a wave of increasingly harsh unilateral and multilateral sanctions on his nation, which is widely considered in the West to be a threat to international security due to its controversial nuclear program. (Memorably, former U.S. President George W. Bush went so far as to include the Islamic Republic in his “axis of evil” during his 2002 State of the Union address.) Rouhani’s election will likely cause Iranian-Latin American relations to again change course, as he appears more interested in increasing constructive engagement with Washington than further solidifying Iran’s alliances with the United States’ southern neighbors.

Photo source: AP via Salon

International Sanctions on Ahmadinejad’s Iran

Iran has been subject to international sanctions since Washington first imposed unilateral sanctions in 1979 in response to the Iranian hostage crisis. Further sanctions placed on Iran continued to be unilateral U.S. efforts until the implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1737 in December 2006. UNSCR 1737 imposed multilateral sanctions on Iran for the first time after the Ahmadinejad Administration’s failure to cease uranium enrichment. UNSCR 1737 combined targeted sanctions on individuals and entities (subjecting them to an assets freeze, as well as a travel ban) with the prevention of material, technical, and financial assistance to Iran’s enrichment-related or nuclear weapon-delivery system activities. [2] Peru and Argentina were both temporary members of the Security Council when it unanimously passed this resolution. In response, Ahmadinejad threatened to suspend diplomatic and economic relations with nations supporting the sanctions, but Lima and Buenos Aires continue to have both types of relations with Iran, most likely for purposes of international trade (as Iran hardly can afford to cut any willing trading partners). [3] Peru and Argentina’s votes in the Security Council marked the first time that Latin American nations joined the United States in officially censuring Iran for its non-compliance with the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which was first publicized by the International Atomic Energy Agency in 2003. [4]

UNSCR 1737 was followed by two more Security Council resolutions in 2008 that banned arms transfers, tightened financial restrictions (including increased vigilance on Iranian banks), and called for cargo inspections. [5] At the time, Panama and Costa Rica were both temporary members of the Security Council and supported the tightening of the sanctions on Tehran. While in recent years Peru has become a more important trading partner for Iran than it was in the past, both countries continue to have very limited diplomatic relations with Iran. For example, the Iranian government does not have a consular office in either country. These U.N. sanctions were augmented by stricter unilateral sanctions put in place by the United States and other nations.

A notable shift in the sanctions regime against Iran occurred again in June 2010, when the Security Council and the United States (in tandem with the United Kingdom) imposed sanctions on the Persian state that were much more comprehensive in nature than the earlier targeted ones. According to the Iran Project, a New York-based nonprofit organization that seeks to improve relations between Washington and Tehran, these new sanctions were “designed to cause severe damage to Iran’s overall economy.” [6] For example, the U.S. unilateral sanctions included measures directly targeting the Iranian Central Bank. [7] Mexico and Brazil were both rotating members of the Security Council at the time, and Mexico voted in favor of the harsher sanctions prescribed in UNSCR 1929. However, Brazil joined Turkey in opposing the resolution. The two emerging powers instead sought support for the breakthrough diplomatic agreement they had reached with Iran in May 2010. The bargain included a fuel swap and was negotiated by the three nations independent of the P5+1, which is the group of countries—consisting of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council (China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States) plus Germany—that has taken the lead on multilateral negotiations with Iran. The P5+1 nations had expressed interest in a similar fuel swap agreement in 2009 and maintain that they hope to reach a diplomatic solution to the Iranian nuclear issue. However, the six nations dismissed the Brazilian and Turkish deal in favor of increasing multilateral sanctions under the terms of UNSCR 1929. [8] Even though the trilateral negotiations ultimately failed, they still marked a major instance of Latin American involvement in the Iranian nuclear talks and signified the region’s growing importance in issues of international security. Brazil’s role in the talks exemplifies the country’s relatively high level of independence and growing influence in global politics, also shown by its continuance of relations with Iran despite the sanctions regime—though Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff has gradually phased back its ties with Tehran in protest of Iran’s human rights abuses.

While the combination of unilateral, coordinated multilateral (such as the U.S.-U.K. 2010 sanctions), and U.N. sanctions makes pinpointing the effectiveness of specific sanctions regimes almost impossible, it is nevertheless clear that the ongoing sanctions against the Islamic Republic are damaging to the nation. Iran is experiencing a number of economic difficulties: the inflation rate reached 45 percent in June, oil exports are falling, and the unemployment rate was at 15.5 percent in 2012. [9] As the Iranian people struggle to make ends meet and contend with shortages of basic goods and pharmaceuticals, pressure has mounted inside the country to adopt softer foreign and nuclear policies in order to negotiate a loosening of the sanctions. This desire for change from within Iran was demonstrated by the mass protests in 2009 and 2010 following Ahmadinejad’s reelection.

Photo source: Washington Post

Ahmadinejad’s Latin America Policy

In the face of crippling sanctions and a struggling economy, former President Ahmadinejad made strengthening Iran’s ties with Latin America a foreign policy priority. Today, Iran has 11 embassies in the region, up from five when he took office. [10] His relationship with former Venezuelan President Chávez was particularly strong and the two leaders united their nations in an “axis of unity” against U.S. “imperialism.” Ahmadinejad flew to Caracas in March in order to attend Chávez’s funeral and again for the inauguration of his successor, Nicolás Maduro, in April. During the Ahmadinejad and Chávez presidencies, their governments also committed to over 100 accords to enhance collaboration between the two nations in fields such as construction and manufacturing—one particularly controversial area of cooperation was uranium mining in Venezuela. [11] However, Iran’s economic woes doomed many of these development projects. Recognizing the precarious state of his nation’s economy, Ahmadinejad also worked to increase economic ties with emerging Latin American powerhouses such as Argentina and Brazil. Ahmadinejad’s interest in Latin America could be seen as a component of his efforts to discredit the United States and decrease support for the U.S.-led international sanctions regime against his country, as well as essential to limiting the damage to the Islamic Republic’s economy by the sanctions as much as possible.

Who is Hassan Rouhani?

President Rouhani is an Iranian cleric and a member of the Combatant Clergy Association political party. The Combatant Clergy Association is considered a pragmatic conservative party, meaning that Rouhani is religiously conservative (like Ahmadinejad) but favors economic liberalization in Iran and greater integration into the global economy. [12] Rouhani’s political mentor and former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) appointed Rouhani the Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council in 1989, a position he held for 16 years until his resignation upon Ahmadinejad’s election in August 2005. However, Rouhani is better known internationally for serving as Tehran’s chief nuclear negotiator from 2003 to 2005, during the administration of then-President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). [13] During this period, he gained a reputation as the “Diplomat Sheikh” as a result of his recognition that some concessions must be made to the West in order to make progress in nuclear negotiations.

However, it is a mistake to portray Rouhani as a moderate and his election as unquestionably a major turning point in Iranian foreign relations. He is highly loyal to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the office of the Supreme Leader—he followed the late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini into exile in the late 1970s. [14] The Ayatollah continues to hold ultimate power over Iran’s nuclear ambitions and other policies, and Rouhani will not challenge this role. While the election of a candidate to the political left of current President Ahmadinejad indicates that the Iranian citizenry may be tiring of his intentional provocations of the West and failed economic policies, it is highly unlikely that Rouhani will undertake all of the major reforms that the country’s economy requires. On the other hand, Rouhani’s negotiating experience and campaign promise to establish a “government of wisdom and hope” are positive signs that a tempering of the Islamic Republic’s traditionally confrontational foreign policy may be in the cards. [15]

Photo source: Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images, via The Guardian

Rouhani’s Expected Latin American Foreign Policy

It is likely that Latin America will become less of a priority for Tehran during Rouhani’s presidential term. As a pragmatic conservative, he is not interested in “deliberately antagonizing” the West, as many saw Ahmadinejad as doing. [16] Rouhani has, however, expressed interest in engaging in a dialogue with the United States and other international leaders like the P5+1 nations about Iran’s nuclear program in the hopes of lightening the sanctions regime. In his first press conference after the election, when asked about Iran’s relations with Latin America, Rouhani stated that Iran’s “priority would be firstly [its] neighbors, the Islamic and non-aligned states” and emphasized the importance of restarting productive nuclear negotiations with the West. [17] However, he also assured reporters that “[Tehran] favor[s] expansion of relations with all countries, including the Latin American states.” [18] Reading between the lines, it seems that Rouhani will not continue outgoing President Ahmadinejad’s focus on cultivating relationships with the Global South, and instead will seek to improve relations with the traditional powers, which he sees as more prudent for his nation’s survival. Rouhani recognizes that negotiating a reduction of the sanctions would be the most beneficial foreign policy maneuver he could engage in, and this necessitates prioritizing a diplomatic thaw with the West over aligning with Latin American nations in protest of U.S. hegemony. However, it is important to note that Rouhani’s Iran may present fewer human rights concerns than Ahmadinejad’s and therefore may prove more attractive to Latin American nations, especially Brazil. If Iranian-Latin American relations strengthen under the new administration, the more probable cause will be interest on the Latin American side than interest on Rouhani’s.

For example, even though Venezuelan President Maduro has announced plans to meet Rouhani and expressed his desire for enhanced cooperation between Tehran and Caracas, Iranian-Venezuelan relations will likely weaken without the strong personal ties between Ahmadinejad and Chávez keeping the two countries close. [19] Both nations are contending with a variety of economic woes; Venezuela also faces shortages of basic goods, such as, most recently, toilet paper and even wine for Communion. Thus, neither Tehran nor Caracas are in a position to significantly help the other economically—the goal of many of the accords signed during the Ahmadinejad and Chávez Administrations. Both nations are instead turning towards Asia as a potential economic savior. Tehran and Caracas are also less relevant to each other’s political goals now than in the previous decade, likely rendering the well-publicized “axis of unity” rhetoric a vestige of the previous administrations.

According to a June 25 State Department report on the role of the Islamic Republic in the hemisphere, Iran’s influence is demonstrably in decline. The report states that, “as a result of diplomatic outreach, strengthening of allies’ capacity, international nonproliferation efforts, a strong sanctions policy, and Iran’s poor management of its foreign relations, Iranian influence in Latin America and the Caribbean is waning.” [20] Despite Ahmadinejad’s attempts to more actively engage with the rest of Latin America beyond established partners such as Venezuela, the international sanctions regime impeded him from making real, sustainable headway into the hemisphere, especially economically. Consequently, Rouhani will experience a similar fate until nuclear negotiations yield positive results and prompt a reduction of the sanctions.

Photo source: Times of Israel

Spotlight on Argentina: Rouhani Inherits Highly Controversial AMIA Case

Rouhani begins his presidential term with a potential diplomatic crisis involving Iran and Argentina to contend with that could hinder his ability to engage with the Latin American nation. New developments regarding Iran’s role in a 1994 terrorist attack in Buenos Aires, including allegations against Rouhani himself, have exacerbated tensions between the two countries. On July 18, 1994, the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina’s (Argentine Israelite Mutual Association; AMIA) community center in Buenos Aires was bombed in the deadliest terrorist attack in Argentine history, with 85 people left dead and several hundred injured. This followed the earlier 1992 bombing of the Israeli embassy in Argentina, for which many suspect that the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah and Tehran were involved. After the bombing, there was a good deal of speculation that the Iranian government was in some way behind the attack and, in 2006, the official government prosecutors for the AMIA case, Alberto Nisman and Marcelo Martínez Burgos, formally accused Hezbollah of carrying out the attack and the Iranian government (then under Rafsanjani) of directing it. Several former and current high-ranking Iranian officials, including two of this year’s presidential candidates, Mohsen Rezai—who is wanted by international policing organizations like Interpol in connection with the attack—and Ali Akbar Velayati, are the targets of outstanding indictments in Argentina. [21]

On a personal level, more concerning for Rouhani are the June allegations by the Washington Free Beacon, a conservative online news source, that he is also responsible for the 1994 bombing in Buenos Aires, despite the lack of any formal charge against him by Argentine authorities. According to 2006 testimony from former Iranian intelligence officer Abolghasem Mesbahi, Rouhani was a member of the special committee—comprised of members of the Supreme National Security Council—that planned the attack. [22] This contention, while debatable due to the questionable veracity of Mesbahi’s testimony, is nevertheless plausible since Rouhani was the secretary of the council at the time. If further evidence backing the Free Beacon’s hypothesis comes to light as the investigation continues, it could prove very damaging to Rouhani’s presidency and particularly to the Islamic Republic’s relations with Latin America.

Photo source: Baltimore Sun

The allegations of Rouhani’s involvement in the attack came as part of increasing publicity of the AMIA bombings after prosecutor Nisman submitted a 502-page indictment to the Argentine government. The indictment reaffirmed Iran’s central role in the terrorist attack and alleged that Iran had created a clandestine network of terrorist cells throughout South America, directly contradicting the aforementioned State Department report that claimed waning Iranian influence in the region. The most recent “Nisman Report,” submitted on May 29 and following up on an earlier report in 2006, came at a very inopportune time for both Argentina and Iran, since they had agreed to establish an independent “truth commission” to investigate the bombing on January 27. The Islamic Republic heatedly maintains that it had no role in the affair, and that the commission will pave the way for intensified relations between the two countries by clearing Tehran’s name. [23] However, the international Jewish community insists that Iran and its leaders be held responsible for the bombing. Pressure has come from within the Argentine administration, especially from Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman, who is close to Argentine President Christina Fernández de Kirchner and has adamantly called for the prosecution of those responsible for the attacks. Many observers have condemned Kirchner for agreeing to the truth commission, seeing it as a politically and economically motivated move rather than one seeking justice for the victims of the terrorist attack.

If President Kirchner feels the need to conciliate the Jewish-Argentine community by adopting a harsher stance regarding Iran and the AMIA investigation, there could be disastrous consequences for the Islamic Republic. On October 27, Argentine voters will head to the ballot box for legislative elections that have the potential to lengthen her time in office. (If her political coalition receives a congressional majority, it could pass a constitutional reform increasing presidential term limits to make her eligible for a third term.) Thus far, Kirchner has pursued much warmer relations with Tehran than her predecessors. Argentina currently does not honor the U.N. sanctions, and stands as the seventh-biggest exporter to Iran after Argentine exports increased from $319 million USD to $1.08 billion USD during her tenure. These exports primarily consist of all-important foodstuffs like corn, soybeans, and wheat. [24] New revelations regarding the AMIA bombing may necessitate a reversal of Kirchner’s Iran policy for domestic political purposes and over human rights concerns, which would deal a harsh blow to Iran as Rouhani assumes the presidency.

Conclusions

The sharp contrast between President Rouhani and former President Ahmadinejad has caused many analysts around the world to predict significant changes to Iran’s foreign policy under the new Rouhani Administration. However, Rouhani’s conservative credentials should not be overlooked in his popular portrayal as a “moderate.” The Supreme Leader ultimately controls the direction of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy and nuclear program, and Rouhani’s loyalty to Khamenei precludes the possibility of him independently engaging in relationships not sanctioned by the Ayatollah. However, he recognizes that a more conciliatory approach to multilateral negotiations is essential to securing a desperately needed loosening of the sanctions regime and reducing the likelihood that the United States or Israel will be tempted to use their military superiority against the Islamic Republic.

Rouhani’s shift back towards traditional Western powers, as opposed to Ahmadinejad’s realignment with the Global South, suggests that Latin American nations should expect their diplomatic connections with Iran to diminish during Rouhani’s tenure, though Tehran’s interest in economic relations will remain strong so long as some Latin American nations maintain their willingness to engage with Iran despite the sanctions regime. In addition to the potential of sanctions violations, questions about Rouhani’s human rights record—in light of recent accusations regarding the AMIA bombing—raise concerns about continuing engagement with the Islamic Republic by Latin American countries, especially Argentina. These reservations existed during the Ahmadinejad Administration as well, with good reason. Iran’s questionable democratic process and non-compliance with international norms and laws regarding nuclear proliferation mean that Latin American governments must carefully consider their relationships with Tehran, especially considering that the U.S. government closely scrutinizes all such interactions. Washington clearly hopes that Iran’s new “moderate” president will find the political will and power to sufficiently reform both the Islamic Republic’s domestic and foreign policy to make his nation less of a questionable partner to Latin America. Though the Iranian government may, in the short run, put its Latin American partners on the back burner in order to focus on the more pressing political question of its nuclear program and to work to mitigate the resultant international sanctions regime, mutual economic interests may revitalize the relationship in the long run. Symbolic of the changing nature of Iran’s relationship with the hemisphere, no Latin American head of state attended Rouhani’s inauguration, even though all were invited by the Iranian government. [25]

Rebecca Lullo, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

[1] Erik Wasson, “White House Congratulates Iranians After Rouhani Victory,” The Hill, June 15, 2013, http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/305797-white-house-congratulates-iranians-after-rouhani-election.

[2] U.N. Security Council, 4106th Meeting, “Resolution 1737 (2006)” (S/RES/1737), December 23, 2006. http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/focus/iaeairan/unsc_res1737-2006.pdf.

[3] “U.N. Passes Iran Nuclear Sanctions,” BBC News, December 23, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/6205295.stm.

[4] “Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Report by the Director General” (GOV/203/75), November 10, 2003, http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Board/2003/gov2003-75.pdf.

[5] Brendan Taylor, Sanctions as Grand Strategy, New York: Routledge, 2010.

[6] William Luers and Priscilla Lewis, “Weighing Benefits and Costs of International Sanctions Against Iran,” The Iran Project, 2013, http://www.scribd.com/doc/115678817/IranReport2-120312-2 – fullscreen.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Colum Lynch and Glenn Kessler, “U.N. Imposes Another Round of Sanctions on Iran,” The Washington Post, June 10, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/06/09/AR2010060902876.html.

[9] “Iranian Inflation Accelerates, Posing Headache for New President,” Reuters, July 25, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/07/25/iran-inflation-idUSL6N0FV1Y120130725; “CIA World Factbook: Iran,” Central Intelligence Agency, continually updated, accessed August 1, 2013, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ir.html.

[10] Steven Stanek, “US ‘Threatened’ by Iran’s Relationship with Latin America,” The National, October 29, 2009, http://www.thenational.ae/news/world/middle-east/us-threatened-by-irans-relationship-with-latin-america.

[11] Joshua Goodman, “Iran Influence in Latin America Waning, U.S. Report Says,” Bloomberg, June 26, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-26/iran-influence-in-latin-america-waning-u-s-report-says.html.

[12] Etel Solingen, Sanctions, Statecraft, and Nuclear Proliferation, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 217-218.

[13] Judith Levy, Ed., “Who is Hassan Rouhani?” Ricochet.com, June 16, 2013, http://ricochet.com/main-feed/Who-Is-Hassan-Rouhani.

[14] Al Jazeera Staff, “Profile: Hassan Rouhani,” Al Jazeera English, June 16, 2013, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/06/2013616191129402725.html.

[15] Li Jianmin, Yang Dingdu, and He Guanghai, “News Analysis: Iran Foresees Victory of Moderate Presidential Candidate Rouhani,” Xinhua News, June 15, 2013, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/world/2013-06/15/c_132457575.htm.

[16] Al Jazeera Staff, “Profile: Hassan Rouhani.”

[17] “President Elect Hassan Rohani Gives First Press Conference,” Trade Bridge Consultants, June 18, 2013, http://tradebridgeconsultants.com/news/government/president-elect-hassan-rohani-gives-first-press-conference/.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Associated Press. “Maduro to Meet Rouhani,” The Hindu, June 19, 2013, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-international/maduro-to-meet-rouhani/article4829059.ece; “Italy, OIC, Venezuela Congratulate Iran on Rohani’s Presidential Victory,” PressTV, June 17, 2013, http://www.presstv.com/detail/2013/06/17/309533/italy-oic-venezuela-felicitate-rohani/.

[20] Goodman, “Iran Influence Waning.”

[21] Dashiell Bennett, “Two of Iran’s Presidential Candidates are Wanted for Murder,” The Atlantic Wire, May 23, 2013, http://www.theatlanticwire.com/global/2013/05/iran-presidential-candidates-bombing/65531/.

[22] Alana Goodman, “New Iranian President Tied to 1994 Bombing,” The Washington Free Beacon, June 19, 2013, http://freebeacon.com/rowhani-may-have-helped-plan-1994-bombing/.

[23] “Iran and Argentina Create ‘Truth Commission,’” Al Jazeera English, January 28, 2013, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/americas/2013/01/20131272055398688.html.

[24] H.C., “Argentine-Iranian Relations: A Pact with the Devil?” The Economist, January 29, 2013, http://www.economist.com/blogs/americasview/2013/01/argentine-iranian-relations.

[25] Antoine Blua, “Rohani’s Election Lacking VIP Allies,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, August 2, 2013, http://www.rferl.org/content/iran-rohani-inauguration/25062421.html.