Despite Peace, Colombian Coca is here to Stay

By Jordan Bazak, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Everyday, on the streets of Washington D.C., someone pays $200 USD for a small bag of white powder. Know as an “8-ball,” this portion of cocaine hydrochloride—cocaine for short—weighs just 3.5 grams. It has traveled thousands of miles and lost a lot of weight. In the remote forests of Colombia, this tiny amount of cocaine began as five pounds of leaves hanging from a six-foot tall coca plant. The leaves were first ground into paste, which was then broken down by various chemicals into the fine white grains popularized on TV and in movies. As the cocaine traveled to market, money lined the pockets of guerilla armies, Colombian cartels, corrupt officials, drug mules, and U.S. gangs. Of the hundreds of dollars spent on the final purchase, the distant Colombian farmer received just 80 cents.[i]

But even given their miniscule share of total revenue, rural Colombians can earn far more growing coca than any legal crop. Income, of course, is just one part of the calculation. Cultivating the illicit plant forces farmers to live outside of legal institutions and the formal economy. At the same time, coca has fueled the activities of violent and extortive groups including paramilitaries, drug cartels, and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia). For those who abandon the crop, lower earnings are a fair price for a clear conscience and increased safety.

The Coca Boom

For many other Colombians, however, the economic appeal of coca is too hard to resist. After years of decline, cultivation of the plant is on the rise. From 2013 to 2015, the area devoted to coca doubled from 48,000 to 96,000 hectares, marking a return to 2007 levels.

There are a number of factors explaining the recent coca surge. First, economic and weather conditions have disproportionately harmed legal crops. In the past two years, Colombia has suffered from high inflation and a growing trade deficit, both results of the drop in global oil prices.[ii] The economic downturn has reduced demand for cacao and plantains, coca alternatives that are primarily sold in domestic markets. Furthermore, the El Niño weather pattern has done more damage to these less hardy crops.[iii] Coca, a durable plant that is mostly exported, is largely insulated against such phenomena.

Another reason for the recent coca boom is the suspension of aerial herbicide spraying in 2013.[iv] The use of spraying to destroy coca fields had created tensions between the government and rural Colombians, whose personal health and legal crops were often harmed by the strategy. Moreover, the tactic was losing effectiveness as growers shifted coca to protected areas such as national parks. Given these diminishing returns, Colombian economists believe the end of spraying to be an insufficient explanation for the latest spike in cultivation.[v]

The final factor, one emphasized by both U.S. and Colombian officials, is the Colombian peace process.[vi] Farmers were well aware that a solution to illicit drug cultivation was a key pillar of the Havana-based negotiations. Growers assumed, or learned directly from the FARC, that the accord would contain benefits to encourage coca farmers to switch to legal crops. To receive these perks, however, one would have to be harvesting coca in the first place. Officials claim that farmers have only adopted the crop to position themselves as beneficiaries of the agreement, after which they will return to legitimate economic activities.

It remains to be seen how the accord’s failure in the October 2 plebiscite will affect coca cultivation. Given that recently planted coca is just now reaching maturity and that a renegotiated peace agreement is unlikely to differ much on this particular topic, new growers have little reason to turn back to legal crops now. The problem could actually worsen. The FARC will need money to continue paying its troops as they return to the negotiating table. Also, a new agreement could very well lack the considerable compensation–$2,500 USD–promised to each ex-combatant in the August accord. Without this transfer, guerillas have a strong incentive to stash away as many illicit funds as possible before reintegration.

Simple Economics

| Crop | Price per Ton | Metric Tons per Hectare | Value per Hectare |

| Coca | $1,100 | 4.7 MT | $5,170 |

| Cacao | $3,000 | .5 MT | $1,500 |

| Palm Oil | $550 | 3.3 MT | $1,800 |

| ——- | Total Value of Crop | Number of Hectares | —— |

| Coffee | $1.157 Billion | 931,058 | $1,243 |

Regardless of the reasons behind the recent increase in coca cultivation, the cash crop’s survival in Colombia and in the greater region has never been in doubt. It is simple economics. The table below shows the annual value produced by one hectare of coca, cacao, palm, and coffee, respectively.[vii] While one hectare of coca produces a value of $5,170 USD per year, one planted with cacao, palm trees, or coffee only yields between $1,000 and $2,000 USD. Bananas, another often-proposed substitute, are reported to yield less than one-third the income of coca.[viii][ix]

| Sources: Coca: UNODC, 2014 Cacao: IndexMundi, 2016; Fedecacao, 2015 Palm Oil: Fedepalma, 2016 Coffee: Federación de Cafeteros |

The Path of Least Resistance

Still, many experts question the overall impact of alternative development. In 2001, Jason Thor Hagen of the Institute for Policy Studies challenged the ability of the Colombian bureaucracy to fully and fairly distribute AD funds.[x] Eight years later, writing for The Nation, Teo Ballvé revealed a number of disturbing incidences in which ex-paramilitary officers had received alternative development funding to grow palm oil on stolen lands.[xi] Although the prevalence of such abuses is difficult to determine, there can be little doubt that poor institutions limit the ability of AD funding to target those truly in need.

But even if Colombia’s bureaucracy were to noticeably improve, alternative development would not be a definitive solution to coca cultivation. According to Luis Carlos Reyes, an economics professor at the University of Javeriana, if the value and productivity of substitutes increased drastically, coca would still persist. The drug industry’s ample profit margins would allow criminal organizations to pay farmers more so that they keep growing the illegal crop.

Professor Reyes is equally skeptical of coercive methods. Both he and Hagen agree that coca production tends to find the path of least resistance. The moving of fields to national parks to avoid aerial spraying is just one example. On an international level, the decline in Colombian coca from 2007 to 2013 was partly offset by an increase of cultivation in Peru.

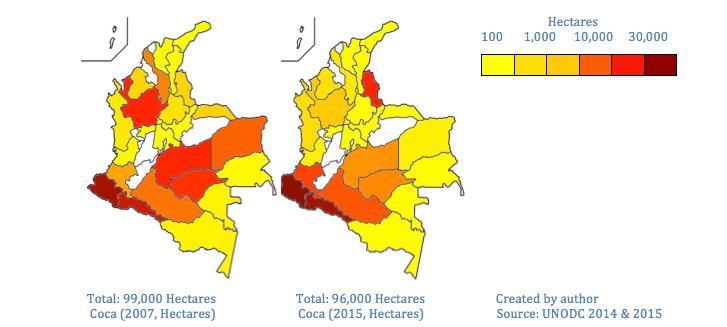

The following charts demonstrate how the geographic distribution of coca within Colombia shifted between 2007 and 2015, years in which total output was more or less the same. In general, coca cultivation moved away from the middle of the country toward more peripheral regions. This shift reflects improved law enforcement, as well as more favorable conditions for alternative crops, in central departments such as Antioquia, Santander, and Meta.

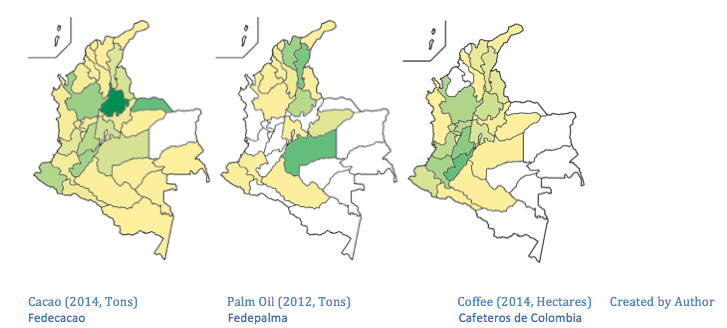

The next set of charts shows the current distribution of cacao, palm oil, and coffee. The commonly proposed substitutes to coca are found in areas where the production of the illegal crop has decreased or was never prevalent to begin with. In the remote and less hospitable departments where coca production has spiked—Putumayo, Nariño, and Norte de Santander—substitute crops have struggled to gain a foothold. This evidence supports the hypothesis that AD and law enforcement efforts are displacing, rather than replacing, coca.

Legalization: A Distant Dream

If Professor Reyes had one wish, it would not be to perfect alternative development. Instead, he would legalize drugs such as cocaine, marijuana, and heroin worldwide. In reality, achieving such a policy would require a miracle. The power of the United States and Europe, regions that bear the brunt of drug usage, precludes any serious attempt at global legalization. Still, its proponents make a compelling case for a world of legal narcotics.

In Colombia, drug legalization would remove the primary source of funding for violent criminal groups. Furthermore, the policy would allow current coca growers to reenter the formal economy. They could secure lines of credit, sign enforceable contracts, and partner with companies to commercialize coca products. Additionally, the Colombian government would be able to tax the multi-billion dollar industry.

It is unclear whether legalization would make coca farmers better off economically. Although they would get a larger share of cocaine’s retail value, this value would plummet rapidly. Once the risk is removed, coca is just a leaf that anyone can grow. It would not be surprising if legalization actually favors alternative crops.

The benefits for United States are less obvious. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) estimates that 1.8 percent of the US population used cocaine during the past year, a smaller percentage than in the 1990s but still 5 million Americans.[xii]

There are good reasons to regulate cocaine. To treat its users as rational actors who have weighed short-run enjoyment against long-run effects would be a gross mischaracterization. Cocaine is extremely addictive and requires escalating doses to achieve the same effects.[xiii] Down the road, the stimulant is known to cause heart attacks, strokes, and birth defects.[xiv] Cocaine use also has strong negative externalities. It can strain healthcare services, scare away potential employers, and place extreme stress on other family members.

But through legalization, the United States would be able to tackle the issue as a public health problem instead of as a crime. In doing so, the government could save billions on policing, prisons, and border control. Furthermore, the millions of Americans either currently in jail or in danger of prosecution for non-violent drug offenses would be able to come out of the shadows and contribute more fully to society.

Would legalization increase cocaine usage? Maybe, but this need not be an inevitable outcome. The government could tax the drug, reducing consumption and raising revenue.

Conclusion

Even with the pending conclusion of Colombia’s 52-year civil war, illicit coca cultivation is unlikely to disappear anytime soon. So long as there exists high international demand and the large profits created by prohibition, new criminal organizations will fill the vacuum left by the FARC. Alternative development programs that raise productivity and forge partnerships between small-scale growers and companies may see some success. However, they should not be viewed as an ultimate answer to the problem. Cultivation will move to new areas or countries where government influence is weaker and alternative crops less viable. A permanent solution to cocaine must also address first-world drug demand and should give serious consideration to legalization, a policy that would allow U.S. drug users and Colombian farmers alike to participate in the formal economy and seek the help they need without fear of prosecution.

By Jordan Bazak, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Original research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews. com and Rights Action.

Featured image: Cocoa03.jpg taken from Wikipedia Commons.

[i] Luis Carlos Reyes, “Se acabará la guerra y seguirá el narcotráfico,” El Espectador, August 31, 2016. Accessed November 3, 2016. http://www.elespectador.com/opinion/se-acabara-guerra-y-seguira-el-narcotrafico.

[ii] “Developments in Individual OECD and Selected Non-Member Economies,” OECD Economic Outlook, 2016 (1). June 1, 2016: 111-113. Accessed October 27, 2016. http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/economics/oecd-economic-outlook-volume-2016-issue-1/colombia_eco_outlook-v2016-1-11-en#page1

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] German A. Ospina, “A New Challenge for the Santos Administration: Colombia’s End to the Aerial Coca Eradication Program,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, June 1, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2016. https://coha.org/a-new-challenge-for-the-santos-administration-colombias-end-to-the-aerial-coca-eradication-program/

[v] Luis Carlos Reyes, Professor of Economics at the Universidad Javeriana. Interview with author. Skype Interview. Washington D.C.-Bogota Colombia, September 28, 2016.

[vi] Nick Miroff, “Colombia is again the world’s top coca producer. Here’s why that’s a blow to the U.S.” Washington Post, November 10, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/in-a-blow-to-us-policy-colombia-is-again-the-worlds-top-producer-of-coca/2015/11/10/316d2f66-7bf0-11e5-bfb6-65300a5ff562_story.html

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Rafael Romo, “Colombian farmers find safety, success in growing alternatives to coca,” CNN, January 21, 2011. Accessed October 27, 2016. http://www.cnn.com/2011/WORLD/americas/01/20/colombia.coca.alternatives/

[x] Jason Thor Hagen, “Alternative Development Won’t End Colombia´s War,” Institute for Policy Studies, May 1, 2001. Accessed October 28, 2016. http://www.ips-dc.org/alternative_development_wont_end_colombias_war/

[xi] Teo Ballvé, “The Dark Side of Plan Colombia,” The Nation, May 27, 2009. Accessed June 15, 2009. https://www.thenation.com/article/dark-side-plan-colombia/

[xii] “Cocaine,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, last updated June 2016. Accessed October 28, 2016. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/cocaine

[xiii] “Cocaine,” Foundation for a Drug-free World. Accessed October 28, 2016. http://www.drugfreeworld.org/drugfacts/cocaine.html

[xiv] Ibid.