Chile’s Hidro Aysén Project Terminated

On June 10, Chilean cabinet ministers, claiming to be acting in accordance with the “complaints presented by the community,”[i] unanimously rejected the Hidro Aysén proposal, a hydroelectric mega project poised to harness hydro-power in Patagonia. For some, the controversial dam proposal was a solution to Chile’s energy crisis. However, for many, the Hidro Aysén plan was an abomination against the environment and indigenous groups who live in the region. The cancellation of this divisive project leaves many wondering what the future holds for Chile’s energy sector.

In wake of Chile’s burgeoning energy crisis, the 10 billion USD project was estimated to produce 2,750 megawatts of electricity.[ii] The energy-starved state has endured a 10 percent increase in electricity costs and experts anticipate that if left unchecked, prices may increase 34 percent in the next ten years.[iii] Chile, a state whose economy relies heavily on the energy dependent copper mining industry, recognizes the need for revitalization of their energy situation. However, the environmental and social implications of Hidro Aysén proved too dire, causing the Chilean government to suffer yet another failed proposal addressing the lagging energy situation.

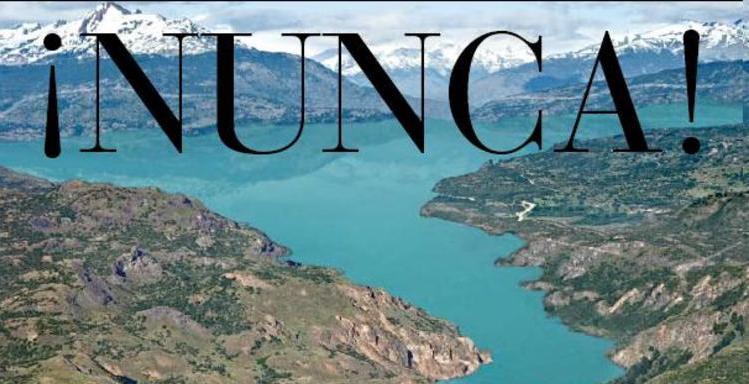

The Hidro Aysén project, introduced in a bill entitled the Environmental Qualification Resolution, has been a topic of stormy debate lasting over eight years. Environmentalists and humanitarians alike have argued that the risks of damming Patagonian waters outweigh its potential benefits. The resistance, spearheaded by the Patagonian Defense Council and 70 other domestic and international organizations, highlighted the adverse impact that the damming would have on the wilderness, wildlife, traditional culture, and the local tourism economy. Environmental criticism of the dam proposal noted that the transportation of 2,000 kilometers of transmission lines necessary to construct the project would require cutting down Patagonian forests and putting many endangered species at risk. In addition to being an eyesore, the mega dam would effectively destroy Chile’s white water rivers while flooding 6,000 acres of land. Other consequences included the lack of relocation space for indigenous and local people which would undoubtedly result in a mass exodus of homeless Patagonian natives. Furthermore, Many Chileans are convinced that damming the beautiful region would negatively affect Patagonia’s flourishing tourism industry.[iv]

Many describe the overwhelming resistance to damming the Chilean landmark region as the “Chilean Environmental Movement’s greatest triumph.”[v] The multi-faceted protest indicates the high level of reverence Chileans have for their natural resources. However, this environmental win comes at a considerable cost. Chile’s energy crisis remains unresolved with no concrete potential solutions. Chile is largely lacking in oil reserves and produces virtually none of its own oil. Chile has been forced to turn to neighboring Argentina which has reduced Chile’s supply in the midst of heightened domestic demand. Sustained tensions between oil rich Bolivia and Chile regarding a century-long border dispute have prevented mutually profitable oil trade between the two countries. Meanwhile, environmental lobbyists in Chile make it increasingly difficult to construct projects using traditional but environmentally destructive means of procuring energy. President Michelle Bachelet admits Chile’s energy situation is “not the best.”[vi] For many, this is an understatement that does not at all address the seriousness of the issue.

As it stands now, the revised Chilean response plan remains dependent on non-renewable sources of energy. President Bachelet has called for unification of Chile’s major energy grids Sistema Interconectado Central (SIC) and Sistema Interconectado del Norte Grande (SING), which are presently divided by a large expanse of desert. Another course of action on her agenda includes increasing competition within the energy industry as it is currently monopolized by three massive companies, Endesa, Colbún and AES Gener. Endesa owns 35 percent of the energy market while AES Gener and Colbún control 18 and 15 percent respectively.[vii] Ideally, with additional market competitiveness, soaring electricity prices will be driven down. Lastly, she calls for construction of a new liquid gas terminal to increase fuel distribution throughout Chile and a reduction in marginal costs of operating energy grids.[viii]

Chile stands on the brink of a serious energy and security crisis. Leaders continue to scramble for solutions that offer no long term solutions in the era of climate change. Cabinet ministers’ decision closes one line of debate only to open others. Chile needs to start making quick decisions regarding their national energy circumstances in order to prevent a potentially catastrophic unfolding of events in the not so distant future. Recent events serve as a double-edged victory: an environmental triumph that will make history but straddles an energy crisis that demands attention and negotiation.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

References

[i] Jamasmie , Cecilia . “Chile Says No to $8bn Hydroelecric in Patagona.” . http://www.mining.com/chile-says-no-to-8bn-hydroelectric-project-in-patagonia-59446/ (accessed June 12, 2014).

[ii] Kozak, Robert . “Chile Rejects Hidro Aysen Hydro Electric Project .” Wall Street Journal , June 10, 2014.

[iii] ibid

[iv] Hill , David . “Chilean Patagonia Spare from U.S. $10 billion Mega Dam Project.” The Guardian , June 11, 2014.

[v] ibid

[vi] Mander , Benedict . “Chile Pulls Plug on $9bn hydroelectric project .” Financial Times , June 10, 2014.

[vii] Mchugh, Emily . “Chile votes 2013: Bachelet says Chile is in danger of ‘major energy crisis’ .” Santiago Times , November 16, 2014.

[viii] L, G. “Keeping the LIghts on .” The Economist , June 11, 2014.

Indent the first line of each endnote.