Honduran Death Squads Murder Peasants in the Bajo Aguán Valley: Reflections on the Bird Report

On February 20, 2013, Rights Action Co-Director, Annie Bird, issued the most detailed report to date on “Human Rights Violations Attributed to Military Forces in the Bajo Aguán Valley in Honduras” (hereafter cited as the Bird Report). [1] The report’s findings remove ambiguities that may have given those who have chosen to remain silent a clear conscience. The Bird Report is far more than simply a compilation of documentation and analysis; it represents an urgent call to stop the killing taking place in this region of Honduras.

There has been no dearth of credible reports of human rights abuses in the Bajo Aguán. The 2011 annual report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR, Chapter 4) is based on the Commission’s own on site observations in May of 2010, correspondence from the State of Honduras, and reports from a number of international human rights organizations and networks, including the International Verification Mission. The Mission visited the area from February 25 to March 4, 2011. Section 295 of the IACHR report states:

During 2011, the IACHR continued to receive troubling reports that the situation in the Bajo Aguán had worsened. There has been a long-standing land dispute between campesinos and businessmen in this area and it has come to the attention of the Commission that as of the June 28, 2009 coup d’état, there has been an increase in the number of deaths, threats and intimidation against campesinos in the area and stigmatization and criminalization of the land rights struggle persists. [2]

The Bird Report provides an important update to the information collected by the IACHR. Bird’s methodology relies in no small part on the testimony of survivors and witnesses who reside in the Bajo Aguán Valley as well as the reports of other human rights defenders and organizations. Bird also gives a general assessment of recent publications by the Honduran Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CONADEH) and by the U.S. State Department Country Reports on Honduras (2010 and 2011). Of these two sources, Bird remarks:

CONADEH and the State Department reported significantly lower numbers of campesinos killed than did human rights organizations and the campesino movements. Further, there was little clarity regarding reports of members of security forces killed. While numbers of killings were reported, there was not confirmation of the identity of the individuals, nor the conditions under which their deaths occurred. Another key difference between U.S. State Department and Honduran government reports and those of human rights organizations was that the State department and CONADEH generally characterized the killings as having occurred in confrontations while human rights organizations denounced … the emergence of a pattern of targeted killings. (Bird Report, p. 18)

By focusing on the details of 34 cases, Bird documents a clear pattern of targeted killings and abductions in the area of the Bajo Aguán, mostly perpetrated against members of campesino organizations. It is important to note that the circumstances of these cases could not reasonably be described as “confrontations.” [3]

The Bird Report shows concrete links between death squads, the Honduran army’s 15th battalion, the Colón police, and a number of private security firms. The document points out that 77 of the 89 killings of peasants reported since January of 2010 “clearly have the characteristics of death squad killings” (p. 43). Bird points to cases where peasants have been murdered while in transit (on bicycles, on motorcycles, in cars, waiting on a bus, or walking along the wayside), at home, while working, at demonstrations, during evictions, or abducted and later found dead, often with signs of torture on the body.

Historical Context

If one deigned to surmise that the days of death squad operations in Central America were over, the Bird Report should provide a deeply troubling signal. Four years ago quarrels over land usage in the Aguán were usually dealt with in court, not through the end of gun barrel. But the political and economic context has dramatically altered in a manner that obscenely valorizes property rights over human life.

According to Just the Facts, Honduras is in a fiscal crisis because of its “inability to pay both its domestic and foreign bills” and it is now faced with the prospect of being “unable to pay for state services ranging from education to security.” [4] One bright spot in the Honduran economy is in the export sector. Since 2000, the demand for African Palm Oil has doubled and the Bajo Aguán is among the ideal places for its cultivation. [5] African Palm Oil is used as a food additive and as a means to produce biodiesel fuel. This growing demand has motivated great interest in the few parcels of land available in the Aguán for expanded levels of cultivation. This already has raised the immediate stakes in the longstanding conflicts between campesinos seeking to reclaim farm land and the three large plantation owners in the area who are bent on enlarging their holdings. The Honduras government did not, at first, countenance murder as an acceptable means of resolving these land disputes. But starting in mid-2009, the legal tools of negotiation all too often have been giving way to the blunt instruments of terror.

On June 28, 2009 a civilian-military coup against the democratically elected Honduran President Manuel Zelaya triggered a crackdown by golpista forces on human rights and progressive activists across the country. Since then, dissident journalists, human rights attorneys, Afro-descendent and indigenous communities, the LGBT community, and political foes of the post coup regimes have suffered the brunt of the abuses, often with the direct participation and complicity of the police and security forces. It is in this precipitous economic, political, and security climate that death squads have surfaced against campesino organizations in the Bajo Aguán Valley. A brief look at the ideological context of the abuse of power shows the complicity (unwittingly or not) of a number of international players.

Ideological Context of Murder in the Aguán, Honduras

Despite an abundance of human rights inspired reporting on this issue worldwide, there has not yet been anything akin to the political will in Tegucigalpa to bring a halt to the targeted killing of campesinos in the Bajo Aguán Valley. How is this major moral failing to be explained given that there is no legitimate policy justification for the carnage over what is essentially a longstanding land dispute among Hondurans?

In the summary section of the Rights Watch Report, Bird describes how certain overarching narratives are used to mischaracterize the ongoing instances of murder being launched in the Aguán:

Impunity surrounding violations is so prevalent that it appears to constitute a policy of the state. Security forces apply the law unequally, criminalizing campesinos while providing protection to the local businessmen, some reported to engage in drug trafficking. High-ranking government officials have distorted the nature of the conflict, accusing campesinos of engaging in criminal activities and claiming that an armed movement is operating in the region, unsubstantiated accusations that wrongly position campesino movements as the object of anti-terrorism and anti-narcotics operations just as regional security initiatives are being promoted by the international community. (Bird Report, p. 4)

The ‘war on drugs’ is being met with growing skepticism both in the U.S. and in the rest of the hemisphere. In the U.S., the unjust application of drug laws to African Americans and the resulting unprecedented rates of incarceration are coming under increasing critical scrutiny by the North American public. [6] At the last Summit of the Americas in Cartagena (April 2012), there appeared to be a growing consensus among the heads of state in attendance of the region’s need to reassess the efficacy and human costs of the war on drugs. With regard to Honduras, the drug war suffered a serious public relations set back after a botched joint Honduran Military—DEA counternarcotics operation that took place on May 11, 2012 in Ahuas (Miskitia territory). This operation left four innocent civilians dead, including a pregnant woman, and four wounded. [7]

In the days and weeks that followed the counternarcotics operation in Ahuas, the international human rights community and some members of the U.S. Congress called for an in depth official investigation of this incident. Washington’s position up to now is to defer judgment on the DEA role in the Ahuas operation to the conclusions reached by the investigation conducted by Honduran authorities. [8] This flimsy approach to accountability in this high profile case is not exactly a confidence builder, but has taken on the appearance of providing cover for suspicious transactions. If Washington is unwilling to investigate the DEA’s “supportive” role in this tragic episode of the war on drugs, it loses leverage in holding Honduran authorities accountable for human rights abuses in Miskitia, the Aguán, and elsewhere in Honduras.

The Bird Report lifts the veil of pretext because it conveys enough testimony from persons on the ground to undermine claims that counternarcotics operations are what chiefly motivates the alliance between the security forces and big agribusiness in the Bajo Aguán. This alliance is supported, whether intentionally or not, by outside forces. For this reason the Report documents some of the U.S. funded military training and other assistance provided to the Honduran military’s 15th battalion and closely related units. This battalion and related units reportedly have been implicated in targeted killings of campesinos who are in most cases associated with farm coop organizations in the Bajo Aguán. So, at this point, it may be prudent for the U.S. to reconsider the controversial deployment of resources for these Honduran military units.

With regard to the money trail, the Bird Report indicates that the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, and a number of other institutions have made loan commitments to the Dinant Corporation. This corporation is owned by Miguel Facusse, who runs one of the three big African Palm Oil plantations in the area. [9] This is important because the Bird Report links a security firm (called Orion Private Security Corporation) [10] in the pay of Dinant and at least one other agribusiness to some of the acts of violence against campesinos associated with several vicitimized coop organizations. These lenders have an ethical obligation to further research and reevaluate any loan commitments to questionable agribusinesses that are alleged to engage in murder for hire and other notorious crimes. Bird’s research, then, helps the readers to connect the dots from the military assistance and money trails to violence in the Aguán.

U.S. Union and Congressional Concern Over Human Rights Abuses in the Bajo Aguán

Since unionists in Honduras are among the most persistent targets of repression it is no surprise that the AFL-CIO and other U.S. unions have urged Congress to act against human rights abuses in Honduras. In a March 2012 letter from a number of U.S. unions to members of the U.S. Congress, the situation in the Bajo Aguán is mentioned in the context of massive violations of human rights in that country:

The violence directed towards the campesinos in the Bajo Aguán represents a fraction of the violence, torture and harassment reportedly undertaken by the Honduran police and military against human rights defenders, trade unionists, peasant groups, and others. We respectfully ask you to sign the letter initiated by Representative Schakowsky calling on Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to immediately suspend all police and military aid to Honduras until the Lobo Administration ends state-initiated violence and impunity, investigates and prosecutes members of the police and military responsible for human rights abuses, monitors the activities of private security companies, and provides basic protective measures for campesino activists, human rights advocates, members of the opposition, and other targeted populations, including trade unionists. [11]

Ninety-four members of the House signed on to Rep. Schakowsky’s (D-IL) Dear Colleague letter (March 9, 2012) which opens: “We are concerned with the grave human rights situation in the Bajo Aguán region of Honduras and ask the State Department to take effective steps to address it.” The letter also urges the State Department to “suspend U.S. assistance to the Honduran military and police given the credible allegations of widespread, serious violations of human rights attributed to the security forces.”

Efforts by governmental and non-governmental human rights organizations, major U.S. Unions, and a significant number of members of Congress have so far not been successful in stopping the human rights abuses in the Bajo Aguán. The push for a change of course, however, continues. On January 30, 58 members of Congress signed a letter to then incoming Secretary of State John Kerry and Attorney General Eric Holder which closes:

“We strongly recommend a review on the implementation of counternarcotics operations carried out by our government in Honduras taking into account the unique conditions and high vulnerability of Afro-descendent and indigenous communities, who are disproportionately affected by drug trafficking activities.” [12]

Perhaps with a change at the helm of the State Department such voices of conscience will prevail. It remains to be seen whether Washington will develop a more progressive and responsive hemispheric policy which makes human rights and mutual respect among nations a top priority.

Urgency of the Now: Policy Recommendations

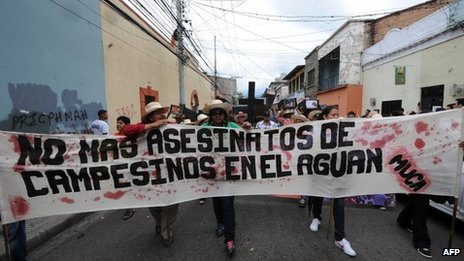

It is of critical importance to note the “urgency of the now” in the Aguán. Since the publication of the Bird Report on February 20, 2013, two more killings in the Aguán have been reported: on February 24, the tortured bodies of Yoni Adolfo Cruz of the Unified Peasant Movement of the Aguán (MUCA) and Manuel Ezequiel Guillen García of the Peasant Movement for the Recovery of the Aguán (MOCRA), were found; they had disappeared on Thursday, February 21. [13]

While the Bird Report provides detailed findings and recommendations, there are two immediate indispensible measures that can help put an end to the killings.

First, the Obama Administration should immediately halt military assistance to all security forces involved in the abduction and murder of peasants in the Bajo Aguán.

Second, the Honduran authorities ought to enforce a return to exclusive reliance on litigation and negotiation as the appropriate means for resolving land disputes and dealing with territorial occupations in the Bajo Aguán region. [14]

Overcoming Impunity

If there is to be a long term and broad cessation of human rights abuses in Honduras, the perpetrators of the murders in the Aguán area and in other locations in Honduras must be held accountable. It is not clear, however, that justice for the victims and their families can be achieved given the current political, judicial, and security situation in Honduras. At the present time, some elements of Honduran the law enforcement forces are implicated in a significant number of human rights abuses, the judiciary stands in serious need of reform, and the country is now being internationally seen as a dangerous place for human rights attorneys. Two of the country’s most prominent human rights attorneys, Antonio Trejo and Manuel Diaz were murdered in September of 2012, and other lawyers have been persuaded by bribes or death threats to mend their principled ways.

With compromised judicial and public security systems in much of Honduras, the International Criminal Court (ICC) appears to be the “court of last resort.” Perhaps as the ICC reviews Honduran cases, those responsible for the abuses in the Aguán and other areas of Honduras will take note that universal jurisdiction in the case of crimes against humanity has no statute of limitations.

Frederick B. Mills, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To read the Bird Report, click here: Human Rights Violations Attributed to Military Forces in the Bajo Aguán Valley in Honduras.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news or analysis on Latin America, please go to: Latin News.

References

[1] Bird, Annie, “Human Rights Violations Attributed to Military Forces in the Bajo Aguán Valley in Honduras,” Rights Action, February 20, 2013, http://rightsaction.org/sites/default/files//Rpt_130220_Aguan_Final.pdf.

[2] IACHR 2011 Annual Report, Organization of American States, 2011, http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/docs/annual/2011/TOC.asp. See also Observaciones Preliminares del la Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos sobre Su Visita a Honduras Realizada del 15 al 18 de Mayo de 2010. Secretaria General de La Organizacion de Los Estados Amercanos, Washington, DC 20006, http//www.cidh.org. Sections 118 – 121.

[3] The 34 cases are further divided into three types: 1) Human rights abuses currently under investigation and prosecution; 2) Cases where some investigative measures have occurred; and 3) Cases widely reported by human rights organizations and the press.

[4] “Just the Facts,” Center for International Policy, the Latin America Working Group Education Fund, and the Washington Office on Latin America, January 30, 2013 http://justf.org/blog/2013/01/30/whats-happening-honduras

[5] John, Mark, “Special Report: Africa palm-oil plan pits activists vs N.Y. investors,” Reuters, http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/18/us-africa-palm-idUSBRE86H09320120718.

[6] See Michelle Alexander (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

[7] Mills, Frederick B., “Death in Miskitia Land and the Search for Justice,” Council On Hemispheric Affairs, June 8, 2012, https://coha.org/death-in-miskitia-land-and-the-search-for-justice/. Some reports claim two of the women killed were pregnant, not one.

[8] Guy, Taylar, “Government won’t probe of DEA raid in Honduras,” The Washington Times, February 12, 2013, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/feb/12/no-probe-of-dea-raid-in-honduras/?page=all.

[9] According to a US Embassy Cable of October 26, 2006 “Dinant is a diversified food products company that uses African Palm oil as an ingredient while exporting the balance, principally to the U.S. Overall, African Palm oil is Honduras’ fifth largest export at $56 million per year.” See http://wikileaks.org/cable/2006/10/06TEGUCIGALPA2030.html.

[10] Niether Bird nor this author makes claims about any other firm which may have the same name, but refer only to the one on the ground in the Aguàn area.

[11] U.S. Union Joint Letter to the U.S. House of Representatives on Honduras Human Rights Violations, March 2, 2012.

[12] Johnson, Hank, Rep. Johnson, 57 colleagues call for investigation into DEA-related killings in Honduras, January 30, 2013, http://hankjohnson.house.gov/press-release/rep-johnson-57-colleagues-call-investigation-dea-related-killings-honduras.

[13] Annie Bird, e-mail message to author, February 28, 2013.

[14] There has not been a total stop to negotiations over land disputes, even during the period covered by the Bird Report.